Nearly 100 million years ago, a shark or ray infected with an ancient tapeworm became stranded on the shore of what is now known as Myanmar. As a dinosaur feasted on the marine creature, it ripped apart the parasite, flinging it into the resin of a nearby tree.

That is the best guess of a scientific team from China, Myanmar, Germany and Britain, led by researchers at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who puzzled over the “bizarre fossil” trapped in Cretaceous amber in northern Myanmar’s Kachin state.

The find is “the first body fossil of a tapeworm”, according to Wang Bo, a professor with the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, in a CAS statement.

Parasitic worms infect all major vertebrates in the world, but have left few traces, partly as a result of living inside another animal’s intestine.

They are also “rarely preserved in the geological record,” due to their lack of bones or exoskeletons, the team said in a paper published by the peer-reviewed journal Geology on March 22.

The Myanmar tapeworm could provide a glimpse into the ancient history of the parasitic worm and open up opportunities to examine soft-bodied organisms often lost in the fossil record, the researchers said.

Until now, the earliest widely accepted tapeworm fossil was in the form of eggs found within fossilised shark faeces dated to 260 million years ago. No convincing fossils of an ancient tapeworm’s body had been found.

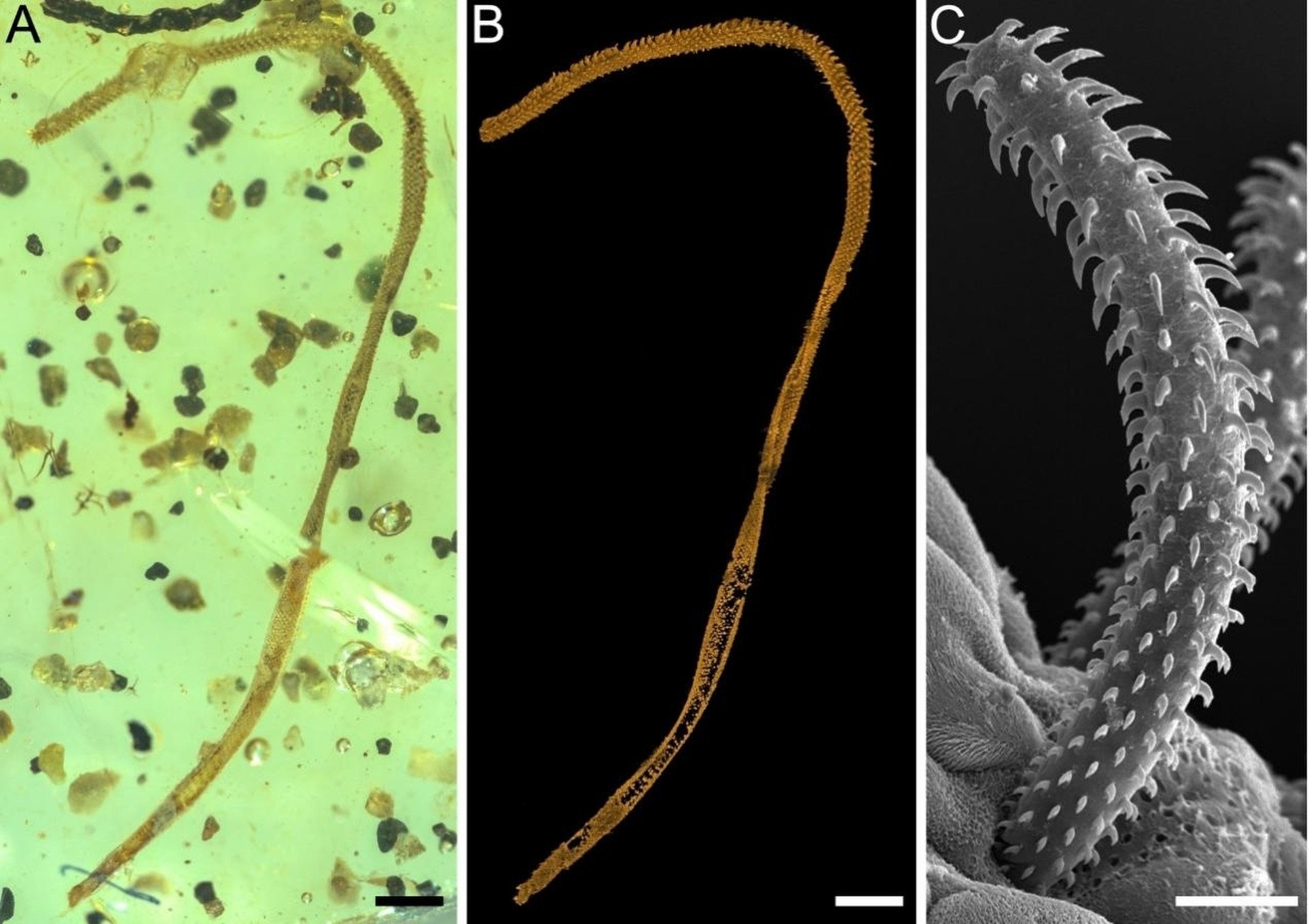

Within the Kachin amber, which dated back to the Cretaceous period around 99 million years ago, the researchers found a tentacle lined with numerous hollow hooks, resembling those found on existing marine tapeworms to hold on to intestines.

These worms live “in the marine environment, parasitising sharks and rays,” said Luo Cihang, first author of the paper and a PhD student at the Nanjing Institute.

Based on the fossil’s characteristics, the team determined that it was not plant or fungus material, nor was it the beak of an arthropod.

“Our study probably provides not only the first partial body fossil of a tapeworm, but also arguably the most convincing body fossil of a flatworm,” in general, the researchers said.

According to the paper, the amber also contained sand, an insect and parts of a fern leading them to conclude that it was preserved in a shore environment. The host animal could have been stranded by a storm or tide, they wrote.

Once the host was stranded on land, it could have been eaten by a dinosaur or other predator while the tapeworm’s tentacle was outside its host’s body. In the process, fragments may have landed in a tree, to become trapped in time by its resin.

“We must note that these scenarios are still speculative and the truth may be far beyond our imagination,” the researchers said. But no matter how unlikely the scenario, “amber has the potential to capture unexpected life details in deep time”.

Luo said the preservation of structures in amber allows researchers to “describe a more complete picture of evolution”.