China’s 2,500-year-old skeletons with legs chopped off may be elites who received ‘cruel’ punishment in ancient times

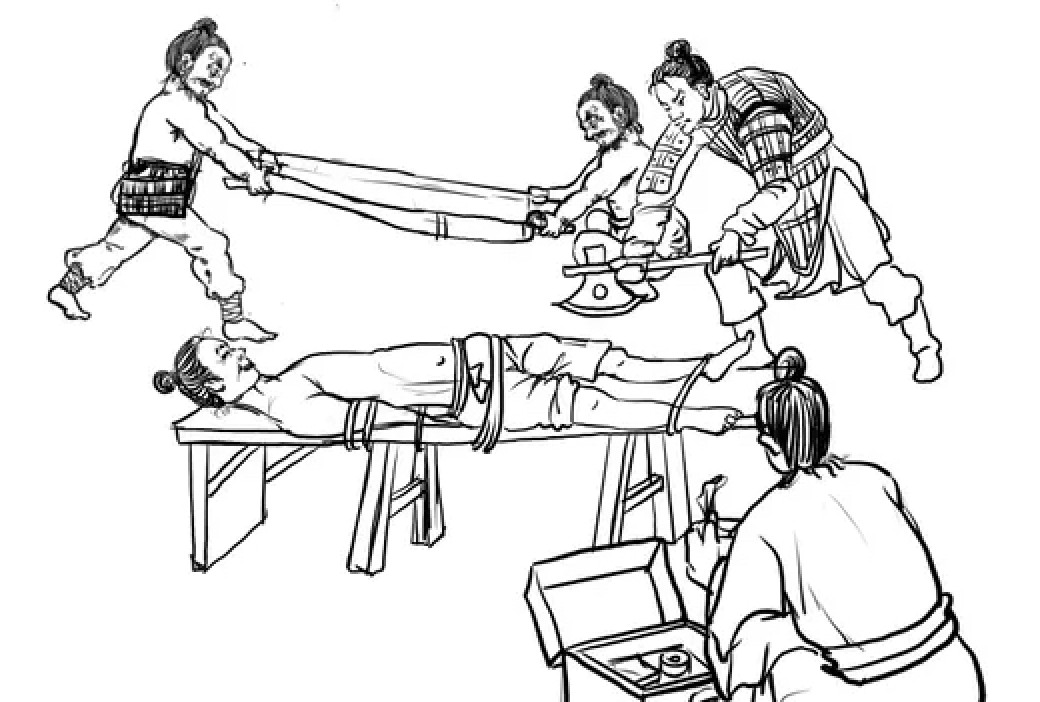

Thousands of years ago in ancient China, felonies were not simply punished with a stint in jail, but serious crimes often entailed the amputation of a limb, specifically legs.

This harsh culture of punishment, known as yue, disciplined people for various crimes, such as desertion from duties, stealing, or defrauding the monarchy. It was also used in lieu of the death penalty.

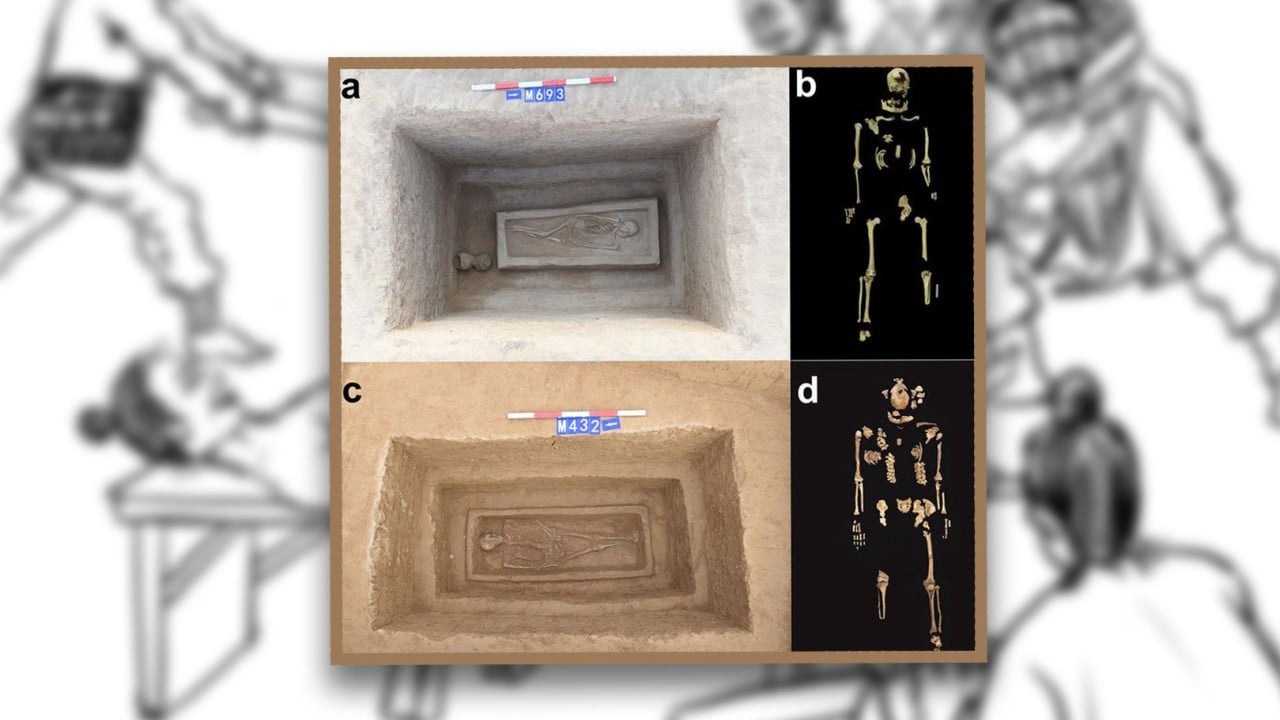

Yue punishment was not relegated to the peasantry, and a study published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences on March 16 detailed how two members of the upper class from the Zhou dynasty (1050-221 BC) in central China’s Henan province were plausibly subjected to yue punishment.

“The sign of punishment by amputation and signs of good post-punishment recovery reflects a well-established amputation protocol, including the post-execution nursing and patient management to facilitate survival and recovery,” Qian Wang, a co-author of the study and a professor at the Department of Biomedical Sciences at Texas A&M University told the Post.

The bones suggested that one man had his right leg removed and the other his left, which could indicate that they were convicted of different crimes. Right leg amputations were administered for felonies deemed more serious than those of left leg amputations. The team also hinted that their fates may have been intertwined.

The existing bones showed signs of a managed healing process, indicating that the lower leg bones were not simply lost to time. Additionally, the top parts of the leg showed evidence that the cuts were clean, suggesting they were not made by repeated blows from a weapon but rather a managed medical procedure.

“Since amputation as a penalty was not an uncommon phenomenon, the two men might have returned to normal social life and buried in a proper manner after death,” said Wang.

The two men likely lived around 550 BC, and the man without a right leg is estimated to have died around the age of 45, while the male without a left leg died at around 55 years old.

They likely lived “above the common class” due to how they were buried, and the researchers analysed historical texts to determine they were likely low-level officials or scholars.

The team acknowledged that other reasons for the amputations were possible, such as congenital disabilities, disease management or ritual amputation.

However, the researchers did not find evidence that other parts of the body had adapted to a congenital deficiency, and they did not find any evidence of ritual sacrifice.

So, that means a “trauma-induced amputation” is the most likely alternative for an amputation, whether it was meant to mitigate the spread of disease or save someone’s life after an accident or moment of violence.

“These reasons need a thorough investigation of trauma patterns and the levels of violence/interpersonal conflict in this region during that time to assess the possibility,” said Wang. “Based on historical and archaeological context, penal amputation is most plausible.”

That being said, the team did not feel confident in their ability to determine what crimes the men had committed.

Punitive amputation is believed to have first emerged in China during the Xia dynasty (2070-1600 BC). Historians have analysed the historical document, The Rites of Zhou, and one chapter of the ancient text describes Xia-era penal punishments that included amputation.

The texts were corroborated with remains found at an Erlitou excavation site in the Yellow River Valley.

During the Zhou dynasty, when the two men lived, documented cases of punitive amputation were widely recorded and the practice was institutionalised.

“In these two cases, the amputees survived because of this refined penal and medical coordination; their above-commoner socioeconomic status might be helpful too in terms of nutrition and adaptation to new life,” said Wang.

There is even a Chinese idiom from the time that says, “Shoes were more affordable because of the volume of people with missing feet.”

While there is no historical data to firmly lock down a mortality rate, Wang said there are two pieces of anecdotal evidence to suggest high survivability for victims.

Research suggests that people of the Zhou dynasty had some knowledge of analgesic medicine to reduce pain. It also seems that people at the time were knowledgeable enough about anatomy to perform procedures like vessel ligation, wound repair, and post-surgery pain relief.

“Because punitive amputation was a regular measure of punishment, it should have had an established protocol for execution with procedures for post-execution management,” said Wang.

Punitive amputation would flourish in China for the following centuries before it was eventually disbanded in 167 BC during the rule of the Wendi Emperor (r. 180-157 BC) during the Han dynasty (202 BC-9 AD).

However, the practice was not totally eradicated, and a skeleton from the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) was found with both feet amputated with a saw.

Other forms of yue punishment for lower-level crimes were also common during the Zhou dynasty, including tattooing people’s faces with the word “criminal”, emasculation, or cutting off the perpetrator’s nose.