Chinese President Xi Jinping must be pleased with the results of his five-day trip to Europe. In his first visit to the continent since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, he spent time in France, Serbia and Hungary, securing important financial deals without expending any significant diplomatic capital.

But Xi’s European tour did not address the long-term challenges that hamper the Sino-European relationship. China is still at risk of a long-term strategic impasse with Europe.

In France, Xi wisely joined President Emmanuel Macron in calling for an “Olympic truce” for the Paris Games in the summer, amid wars in Ukraine and Gaza. In doing so, Xi came across as a statesman of peace while having to invest extremely little actual political capital in what many would see as a reasonable gesture.

In Serbia, Xi met his counterpart, President Aleksandar Vucic, a friendly leader who has opened the country’s economic doors wide to China through infrastructure projects such as the takeover of Smederevo steelworks, building of Pupin Bridge and development of Zijin Mining’s copper basin. Serbia’s economy is small but its welcome for the Chinese president was warm.

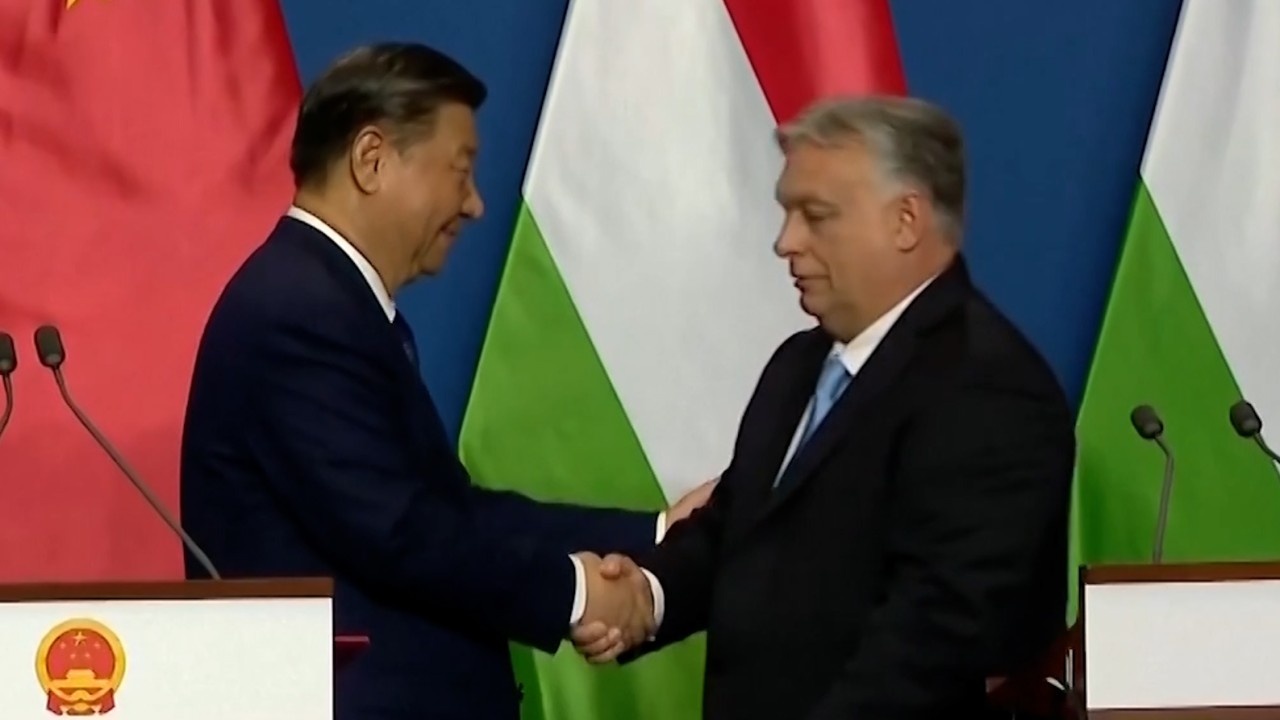

It was in Hungary, however, that Xi was truly celebrated. In Budapest, he and Prime Minister Viktor Orban hailed their countries’ blossoming economic relationship, which will see Chinese electric vehicle maker BYD open its first factory in Europe in southern Hungary’s Szeged, expected to produce 200,000 EVs a year. Work on the China-backed Budapest-Belgrade high-speed railway is also proceeding apace.

All these developments highlight the strength of an emerging and China-friendly Hungarian-Serbian axis in Europe.

However, China still faces unresolved challenges when it comes to its relationship with the European Union. Many problems remain on the table and by focusing on Hungary and Serbia, China does not solve any of them.

In the short term, cosying up to Orban can come at a huge cost to Xi’s reputation. Over the years, the Hungarian leader has acquired semi-pariah status among the majority of European leaders. His government is viewed as authoritarian, illiberal, populist, nationalist and even xenophobic. Most European capitals are extremely wary of any policies originating from Budapest.

To most European leaders, being endorsed by Orban is not a badge of honour. Indeed, it is seen as something to be avoided as much as possible. By associating closely with Orban, Xi runs the risk of the Hungarian leader’s very poor reputation negatively affecting China’s image in the rest of Europe.

In the medium term, it is questionable whether Orban might really be the best choice for China when it comes to looking for friends in Europe. Sure, things will run smoothly as long as he is in charge in Budapest. But – despite its many serious flaws – Hungary is still a democracy.

Sooner or later, Orban will lose his grip on the political patronage system he has nurtured over the years and the power that comes with it. Any new government taking over from him is likely to be far more liberal and pro-EU. Such a state of affairs would spell trouble for China and also put at great risk the political and economic inroads made so far.

In the long term, there is a risk that China might be overestimating the benefits of the leverage that Beijing is buying in Budapest in terms of its relationship with the EU. While Orban is likely to try and counter any EU foreign policy initiatives that Beijing might view as threatening to its interests or its proxies, a trend is clearly emerging whereby other European capitals are learning to cope with Budapest’s antics.

When Orban tried to veto additional EU financial support for Ukraine’s defence against Russia, other EU member states simply let it be known they were prepared to sidestep Hungary to provide financial help. Additionally, other European capitals floated the idea of invoking Article 7 of the Treaty on EU, which could lead to Hungary being stripped of its European Council voting rights. Orban promptly backed down.

As work is under way for the EU to shift its foreign policy decision-making process from unanimity to a qualified majority vote, Hungary will eventually be systematically relegated to a losing position within the European Council. Any remaining influence China might have over European foreign policy through the leverage that Beijing holds in Budapest will be lost.

As for Belgrade, the leverage it has with other European capitals will remain extraordinarily limited until Serbia is allowed to join the EU. And that is very unlikely to happen as long as Vucic remains in power.

Xi is a master of diplomacy and he handled his trip to Europe extremely well. However, one must question if China’s long-term strategic posture vis-à-vis Europe is the most appropriate. Brussels and most European capitals might very well welcome an enhanced role for Beijing on the global stage and in Europe’s economy.

But by becoming so friendly with the two leaders with possibly the worst reputations in Europe, China risks tarnishing its image in the eyes of the rest of Europe, while reaping economic and political gains that are merely superficial and for the short term.

Matteo Garavoglia is professor of practice and research director of the China-EU Centre at Tsinghua University in Beijing. He is also a senior research associate at the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations