In the second instalment of his exclusive monthly series for the South China Morning Post, American theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek reflects on the revolutionary future heralded by Heisenberg’s 1925 paper, with the UN marking its 100th anniversary as The Year of Quantum Science and Technology. Read the previous article here.

Advertisement

The United Nations has declared 2025 to be “The Year of Quantum Science and Technology”, in honour of the centenary of Werner Heisenberg’s paper, “Quantum-mechanical reinterpretation of kinematic and mechanical relations”. In that paper, Heisenberg proposed to build physics on a new foundation.

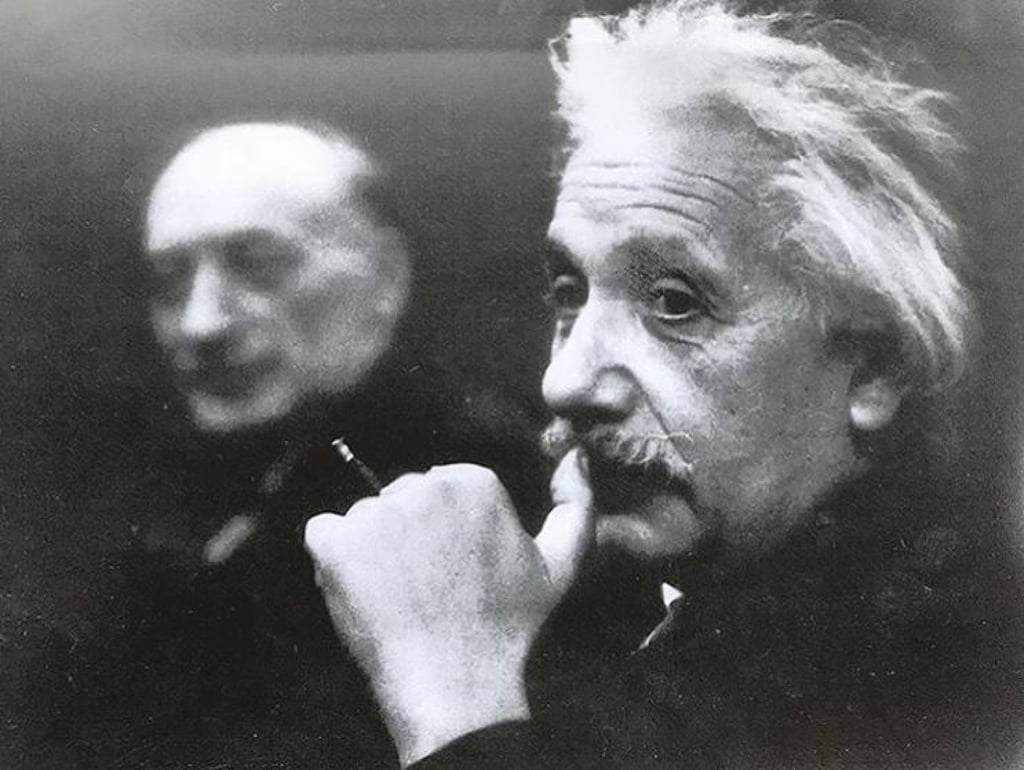

The new methods he proposed were strange and unfamiliar to the physicists of 1925. But it was clear to everybody – after the success of Albert Einstein’s idea that light waves sometimes behave as particles, and of Niels Bohr’s idea that electrons in atoms do not move continuously, but sometimes jump – that the old foundations were failing.

These ideas of Einstein and Bohr flatly contradicted basic principles of classical physics, and they failed to supply a fully logical substitute.

Einstein himself expressed the situation beautifully, in a tribute to Bohr’s work: “That this insecure and contradictory foundation was sufficient to enable a man of Bohr’s unique instinct and tact to discover the major laws of the spectral lines and of the electron shells of the atoms together with their significance for chemistry appeared to me like a miracle – and appears to me as a miracle even today. This is the highest form of musicality in the sphere of thought.”

A new generation of physicists pursued the new ideas vigorously. Not coincidentally, many of the revolution’s leading figures were remarkably young at the time. (In 1925, Heisenberg was 24, Paul Dirac was 23, while “old man” Erwin Schrödinger was 38. Heisenberg got the physics Nobel Prize in 1932; Dirac and Schrödinger shared it in 1933.)