Malaysia has big semiconductor ambitions.

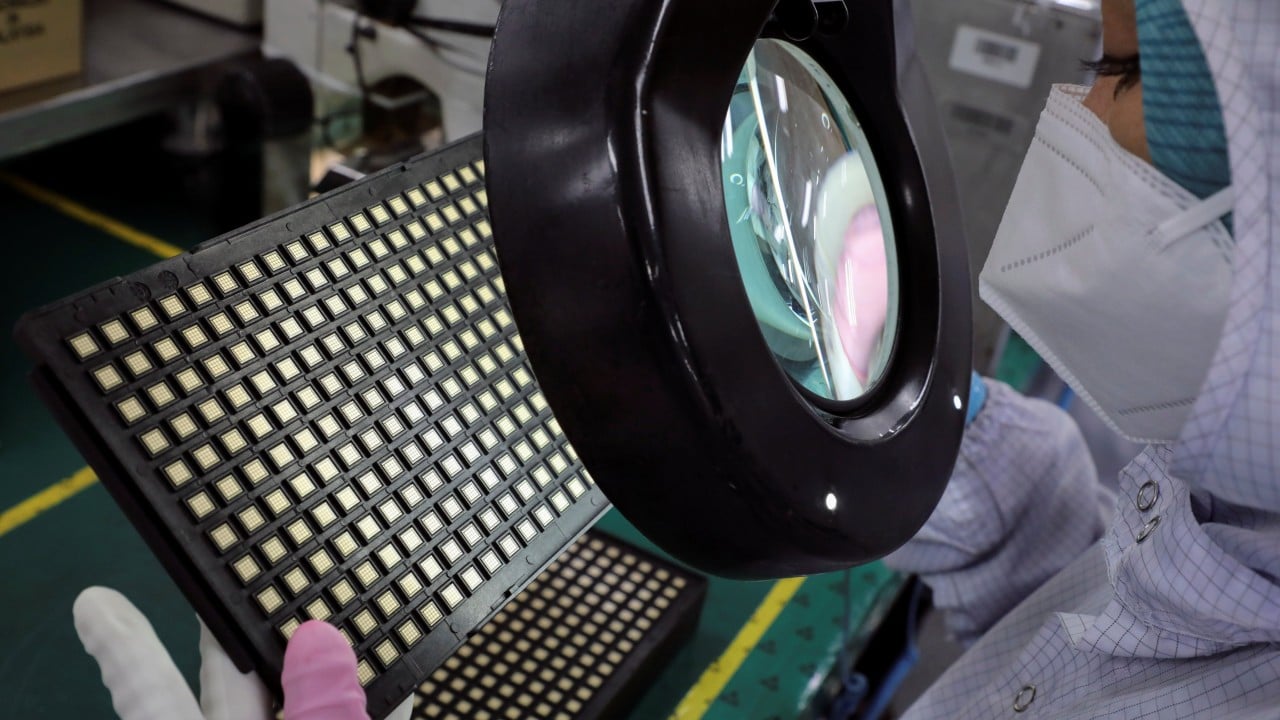

The Southeast Asian nation is already a major cog in the global supply chain, feeding about 13 per cent of demand in the packaging and testing space.

But it wants to be more.

Global semiconductor firms have been shopping around the region for suitable locations to either expand or shift their operations out of China, to “de-risk” from sanctions imposed by the US in an increasingly testy tech war.

This involves tens of billions of dollars in investments and the building of highly coveted wafer fabrication plants, or fabs, which developing nations believe will help fast track their growth towards becoming hi-tech economies.

Malaysia – much like Vietnam, Indonesia and India – wants in on the fab action.

Southeast Asia has already seen a flurry of fresh investments, amounting to billions of US dollars. But these have mostly focused on back end processes, as Washington looks to keep the more lucrative, and highly sensitive, front end wafer manufacturing among its closest allies in Europe and Japan.

Last week, in his strongest pitch yet, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim told a regional semiconductor industry conference in Kuala Lumpur that Malaysia was their best bet to avoid getting caught in the US-China crush, leveraging the country’s long-held policy of neutrality and non-alignment.

It’s arguably an attractive proposition. Anyone who sets up shop in “friend to all” Malaysia can conceivably claim that they are not acting for or trying to undermine any side.

This stance theoretically enables companies to engage with and sell to any party seeking to do business in the country – barring those entities or nations facing multilateral sanctions – allowing Malaysia to maximise the opportunities and profit.

For Malaysia, a surge in semiconductor investments would help speed up its transition to developed nation status, as more plants mean more jobs, including high-skilled roles that will boost per capita income.

But nations, like people, tend to have different motivations.

Malaysia is heavily reliant on external trade, which was a key driver of its rapid industrialisation from the 1980s to 1990s and remains an important contributor to economic growth.

Its often stated position of neutrality has been useful in paving the way for establishing bilateral ties, especially economic links, with numerous nations across the globe.

What happens when one of your biggest partners starts pressuring you to pick a side?

But what happens when one of your biggest partners starts pressuring you to pick a side?

Just last year, the US and EU envoys to Malaysia sent a letter to the government warning of national security risks associated with allowing Chinese tech giant Huawei to develop 5G infrastructure.

Analysts only expect such pressure from the US to intensify, especially if it escalates its sanctions and policy responses against China’s access to high-end chips that can be used to run supercomputers and develop sophisticated artificial intelligence.

The US began unilaterally imposing sanctions on China in the form of export controls under the 2022 Chips Act, which bars chip makers that have interests in the US from expanding semiconductor manufacturing in China or any country deemed by the Americans as posing a national security risk.

Malaysia has made it clear that it will not recognise any sanctions unless approved by multilateral bodies such as the United Nations.

Prime Minister Anwar himself has repeatedly said that Malaysia will not allow itself to be pressured into taking a position for or against any country.

But balancing Malaysia’s interests with the US, its biggest investment partner, and China, its top trade partner for 15 years as of 2023, will need more than bold public pronouncements.

As Anwar’s government pursues the reforms he long championed while in opposition, he will also need to consider putting the right people in the right positions to craft a convincing and actionable policy of engagement to manage ties with the two superpowers going forward.