Beijing’s diplomats have continued to be active on the international stage, keen on positioning China as a global peace mediator. On July 28, China’s special representative on Eurasian affairs Li Hui embarked on his fourth round of shuttle diplomacy on the Ukraine war, travelling to Brazil, South African and Indonesia.

China’s renewed attempts at shuttle diplomacy offer insights into Beijing’s intensified interest in resolving the Russia-Ukraine war.

Li conducted his first round of shuttle diplomacy in May last year and his second round in March this year. Both rounds involved trips to Russia, Ukraine and European nations which have been supporting Ukraine.

In his third round of shuttle diplomacy in May, Li travelled to Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. He also had discussions with officials from Brazil, Indonesia, South Africa and Kazakhstan.

A new six-point consensus statement emerged as a result of the third round of shuttle diplomacy which to some extent attempted to develop China’s controversial 12-point peace plan of February 2023.

Very few countries could have objected to the new document, which merely spelled out generally understood principles for negotiating the resolution of a war scenario, such as observing the “three principles” of de-escalation, focusing on dialogue and mediation as the solution, increasing and improving humanitarian assistance to the people on the ground, opposing the use of nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons, opposing attacks against nuclear power plants, and strengthening collaboration on issues related to global supply chains.

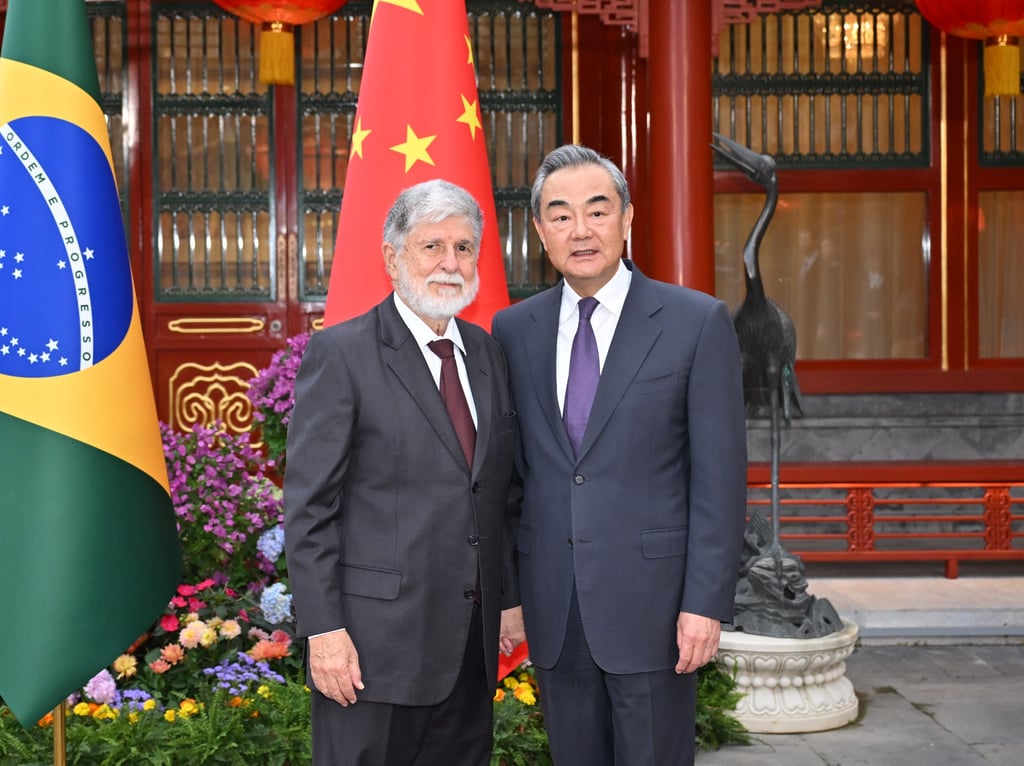

This consensus was further formalised after Celso Amorim, chief adviser to the president of Brazil, met Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Beijing on May 23. But, in a change from the previously published statement, the two officials outlined in the second point that they “support an international peace conference held at a proper time that is recognised by both Russia and Ukraine, with equal participation of all parties as well as fair discussion of all peace plans”.

They remained less specific on the nature of these negotiations and whether any preconditions ought to be met before such talks can commence.

The agreement on holding a peace conference came just three weeks before the peace summit held in Switzerland in June. While Beijing intially communicated with Switzerland on the conference, in the end Beijing did not attend it as Russia had not been invited to participate. While the summit saw attendance by 92 countries, including almost 60 heads of state and government, it proved rather fruitless.

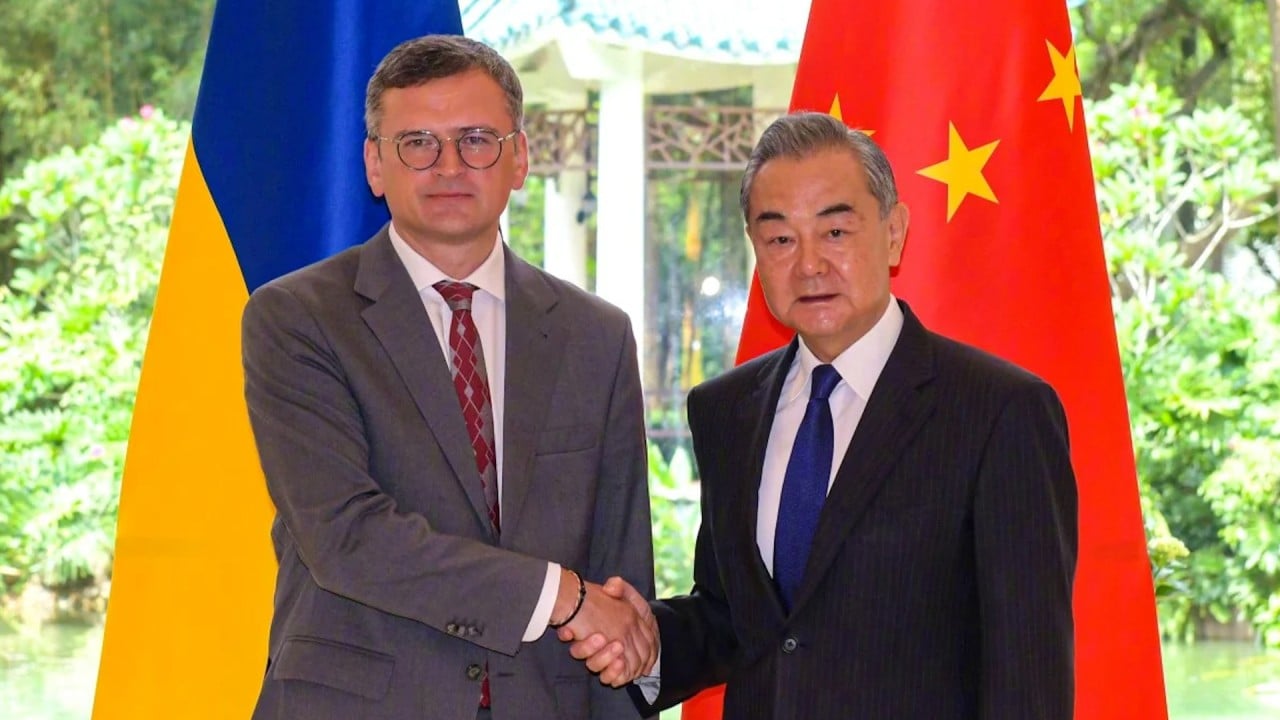

The shuttle diplomacy conducted by Chinese diplomats within the last 14 months has also included bilateral meetings at ministerial level. On July 24, Wang met Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba in Guangzhou. They discussed the “search for ways to stop Russian aggression and China’s possible role in achieving a lasting and just peace”, according to Ukraine’s foreign ministry.

A day later, Wang met Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov on the sidelines of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations summit meeting in Laos. Not surprisingly, Lavrov “welcomed Beijing’s initiatives to promote approaches taking into consideration the interests of all the stakeholders and addressing the causes at the root of this conflict”.

However, Lavrov did not mention the role Russia as the aggressor could play in ending the war. He also did not mention any territorial concessions Russia might be ready to make.

China’s at times hectic diplomatic activities related to the Ukraine war offer three insights into Beijing’s possible future role as mediator.

First, Chinese diplomacy on the Ukraine war has intensified. It took Beijing until the first anniversary of the war to conduct its first round of shuttle diplomacy, but since March this year, over the course of four months, China has conducted three more rounds of it.

Second, Beijing has expanded its diplomacy from primarily focusing on Russia, Ukraine and European nations to also formally including countries with no direct stake in the war.

Finally, Beijing is attempting to build up its image as a global security actor and peace mediator. China’s recent hosting of 14 Palestinian factions, including Fatah and Hamas, which led to the signing of “Beijing Declaration” on July 23, is a case in point.

China’s shuttle diplomacy indicates that Beijing will increasingly urge the finding of an end to the war, but it also begs the question of why these efforts picked up following the second anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Multiple reasons may be at play: China’s global positioning as a security actor, the US’ preoccupation with domestic politics, the increasingly strengthened China-Russia partnership and European countries seeking to resolve the war.

While Kuleba’s visit to Guangzhou portrays Ukraine’s understanding that China will play a role in the resolution of the war, Kyiv is not convinced that China is willing or able to bring about a credible peace settlement. Rather, with the inclusion of countries beyond Europe in China’s shuttle diplomacy, Beijing appears to be signalling to the world that the West is increasingly isolated in its approach to the war and that Russia must have a seat at the table.

Still, policymakers in Beijing have also become increasingly concerned about the potential implications of the Ukraine war – and its possible escalation – for China and the region. Instead of waiting for the new American president to take the initiative come January, China has decided to act itself.

Klaus W. Larres, PhD, is the Richard M. Krasno distinguished professor of history and international affairs at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill

Lea Thome is the Schwarzman fellow at the Wilson Centre, affiliated with the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States