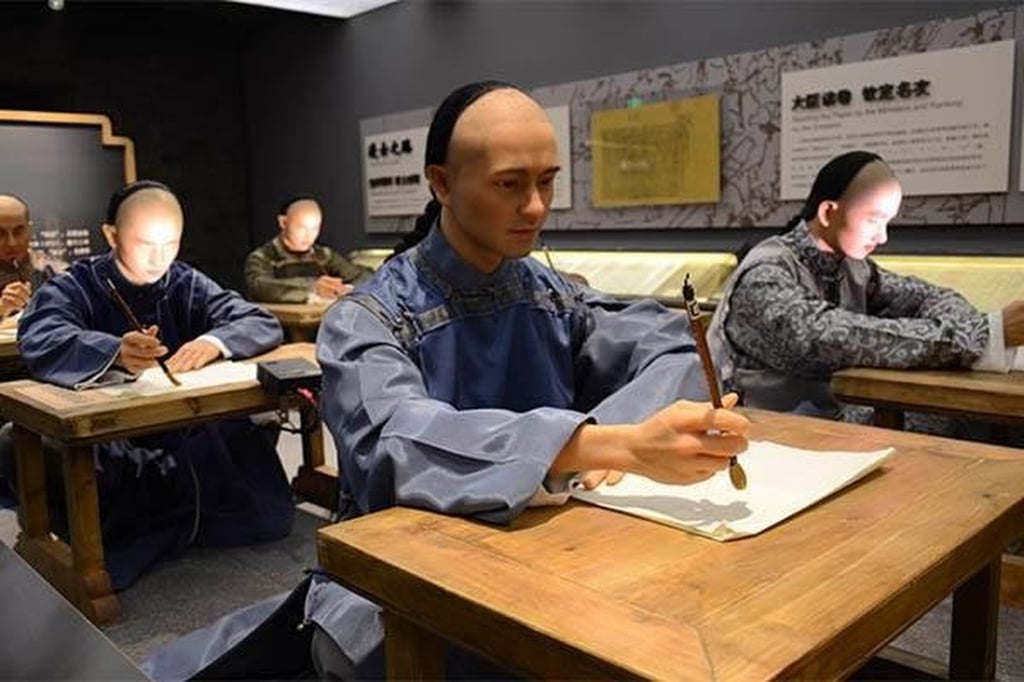

China’s ancient imperial examination, which was no easier than today’s competitive college entrance exam, took into account candidates’ looks when selecting.

Advertisement

The ancient exam, which lasted from the Sui dynasty (581-618) to the late Qing dynasty (1644-1912) before its abolition in 1905, was a system that selected state bureaucrats based on their merit rather than blood.

As the system became well established in the Song dynasty (960-1279), the exam was held once every three years.

The content of the exams varied in each dynasty, but did not deviate from Confucian classics, article writing, history and politics.

A successful candidate was required to go through three levels of preliminary tests held locally to qualify for higher levels of exams.

There were three higher levels of exams: provincial, metropolitan and palace, awaiting the candidates.

The final round of the palace exam was established in the Tang dynasty (618-907), and the emperor hosted the exam and rated the candidates.

Advertisement