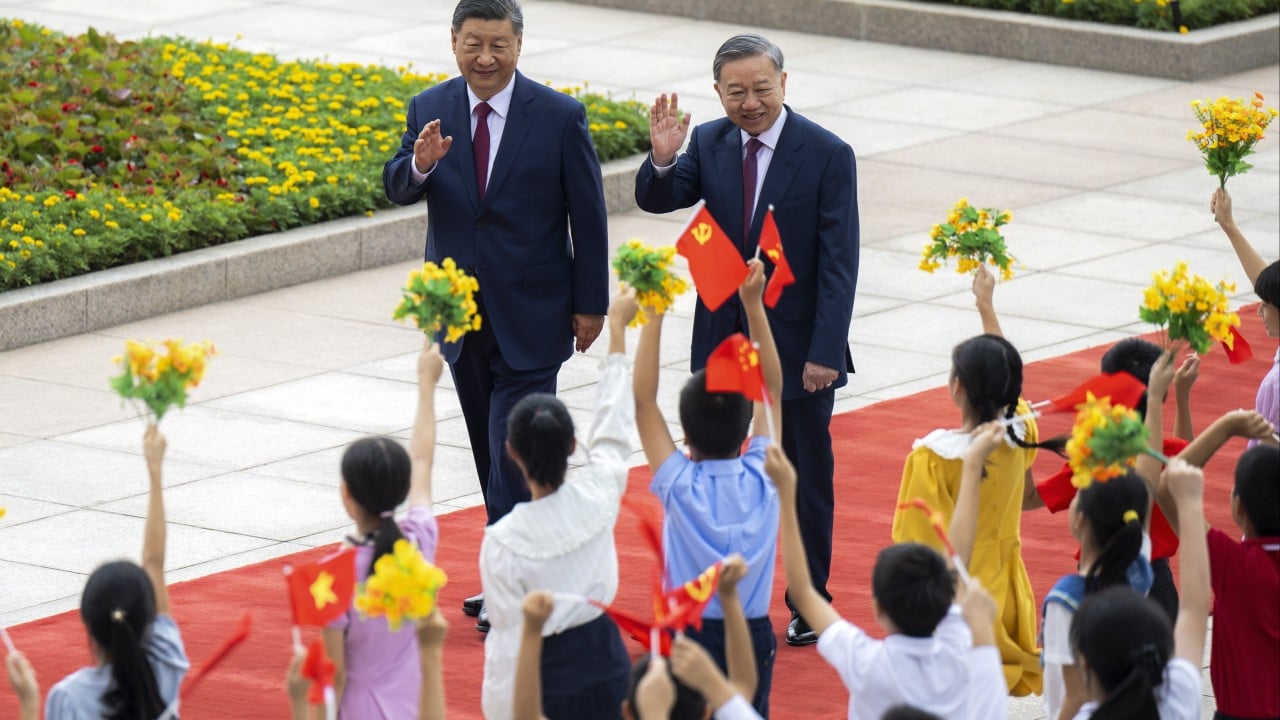

In what was outgoing Vietnamese President To Lam’s first international trip since his appointment as the Communist Party of Vietnam’s general secretary, Beijing and Hanoi signed 14 deals, from cross-border railways to crocodile exports. Lam characterised bilateral ties with China as a “top priority” and described his trip as “the affirmation of the Party and the Vietnamese government to value the relation[ship] with China”.

The joint statement said the two ruling parties were carrying out a historic mission while striving for people’s well-being, national development and peace, reaffirming their commitment to deepen their comprehensive strategic partnership and building a China-Vietnam community with a shared future.

During Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Hanoi in December, the two sides signed a series of cooperation documents in areas including infrastructure, trade and security, as well as reaching a historic milestone when they announced a China-Vietnam strategic community with a “shared future”, a recurring reference that potentially suggests Hanoi has aligned itself with Beijing’s vision.

In December, Vietnam expressed its support for China’s Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Civilisation Initiative, saying these programmes were aimed at protecting common interests of all mankind, promoting peace and creating a better world. Hanoi has now agreed to step up cooperation within these frameworks, which could be seen as a diplomatic win for China.

Lam’s pursuit of closer ties with China echoes that of his late predecessor, Nguyen Phu Trong, who in February exchanged Lunar New Year greetings with Xi and wished for healthy development in the bilateral relationship to benefit the people and contribute to peace and stability.

Earlier this month, Lam vowed not to make any changes to Vietnam’s foreign policy, and focus on advancing the country’s socioeconomic development goals. His trip to China shows he hasn’t strayed from that pledge.

Soon after Lam’s election as party general secretary, US President Joe Biden sent a congratulatory message, expressing his and Vice-President Kamala Harris’ desire to work with him on advancing bilateral relations.

But Washington’s message came as the Biden administration rejected Vietnam’s request to classify it as a market economy, despite upgrading bilateral ties to a comprehensive strategic partnership last September and hailing Hanoi’s “progress in [making] significant market-based economic reforms”.

The rejection dealt a blow to Vietnam’s “bamboo diplomacy”, which seeks to balance ties between the US and China. The US decision could have prodded Vietnam into strengthening economic ties with China. However, the move is unlikely to inflict any significant damage to US-Vietnam relations, given that it enjoys a large trade surplus with the United States, at almost US$105 billion in 2023 and around US$56 billion for the first half of this year.

China is Vietnam’s second-largest export market with bilateral trade amounting to about US$172 billion. However, its trade deficit with China rose by more than 56 per cent to over US$32 billion in the first five months of 2024, signalling the importance of the US as Vietnam’s largest export destination.

Meanwhile, China is increasing its investments in Vietnam. Last year, it invested about US$4.5 billion in the Southeast Asian country, according to Vietnam’s Foreign Investment Agency, up 77.6 per cent from 2022. In the first seven months of 2024, Chinese investments in Vietnam surged more than sevenfold.

Prior to the China-US trade war, many labour-intensive, low-valued-added industries had moved from China’s coastal areas to Vietnam. The trade war has provided Vietnam with an opportunity to take advantage of its geographic location and lure Chinese companies to relocate their production facilities and invest in advanced industries such as electronics and automotive components to help advance its economy and become a technological power.

And not only does Vietnam seek to learn from China’s high-speed rail networks and link up with large Chinese development strategies, it also believes China has a key role to play in regional and global development.

This was arguably reflected in Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh’s remarks during June’s World Economic Forum conference in Dalian, Liaoning province. Underlining China’s “important role” in the world’s development, he vowed to work with Beijing to build a “community with a shared future.” He also recalled a quote from Vietnamese revolutionary Ho Chi Minh to “congratulate China, thank China and learn from China”.

Vietnam’s proximity to China, territorial disputes in the South China Sea, large deposits of rare earth minerals estimated at about US$3 trillion and its potential as an option for the US “friendshoring” strategy have sharply raised American interest in the region.

Yet, by signing new deals with China, agreeing to deepen cooperation in defence and security, boost economic, trade and investment cooperation, and attempting to resolve territorial disputes, Vietnam is charting its own policy in a bid to make ensure it doesn’t miss the boat to become the world’s factory.

US Undersecretary of State Uzra Zeya’s trip to Vietnam last week to “highlight the strength and dynamism of the US‐Vietnam relationship” seems to underscore an urgency within the Biden administration to ensure Hanoi does not get too close to Beijing.

Vietnam’s “bamboo diplomacy” appears to be working, for now. However, that might all change should Donald Trump, who opened an investigation into Vietnam’s trade practices as president, return to the White House and test this diplomacy with his harsh rhetoric and punitive tariffs.

Azhar Azam is geopolitical analyst with a keen interest in economy, climate change and regional conflicts