Khải Huyền wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on July 29, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.

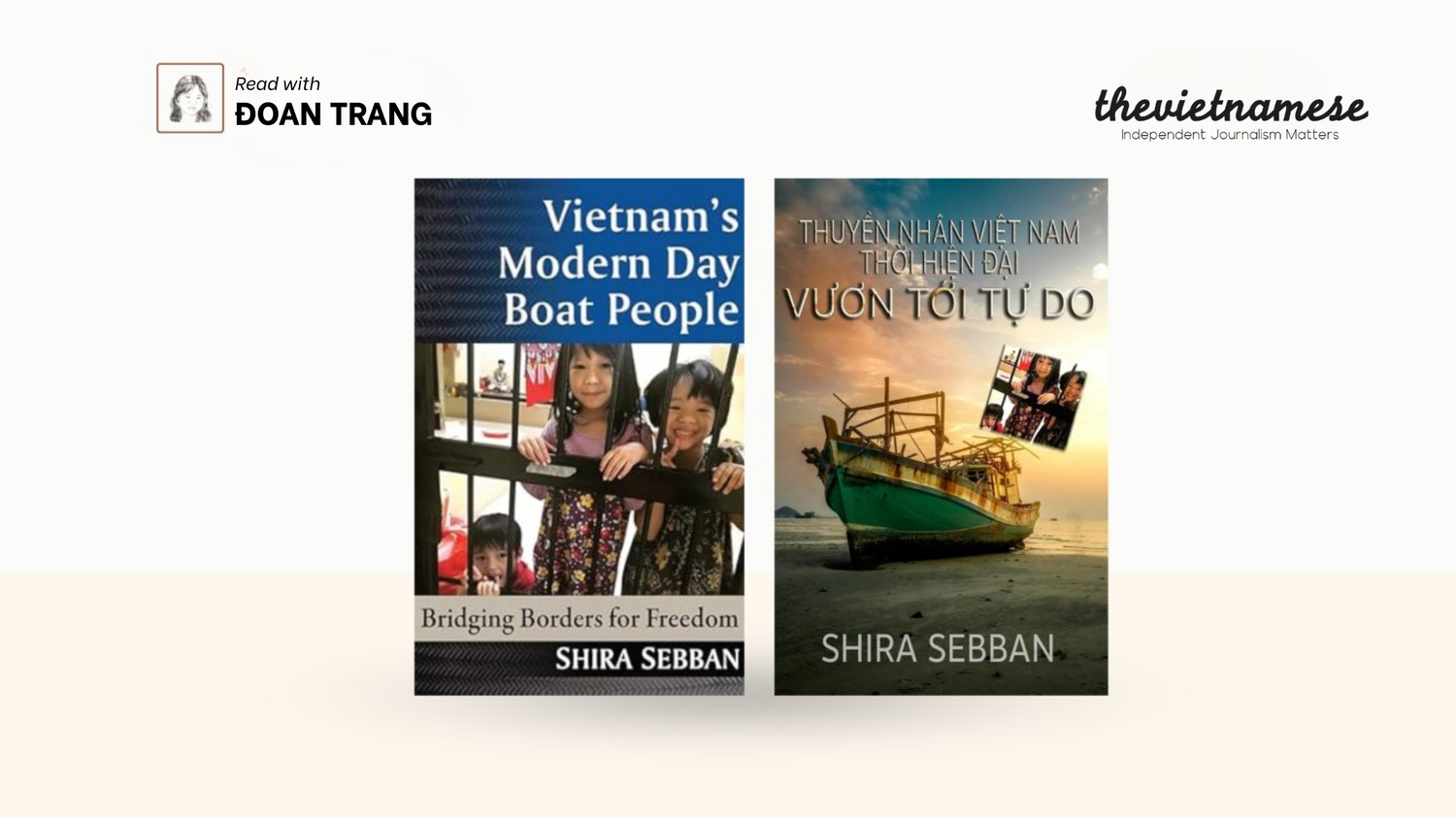

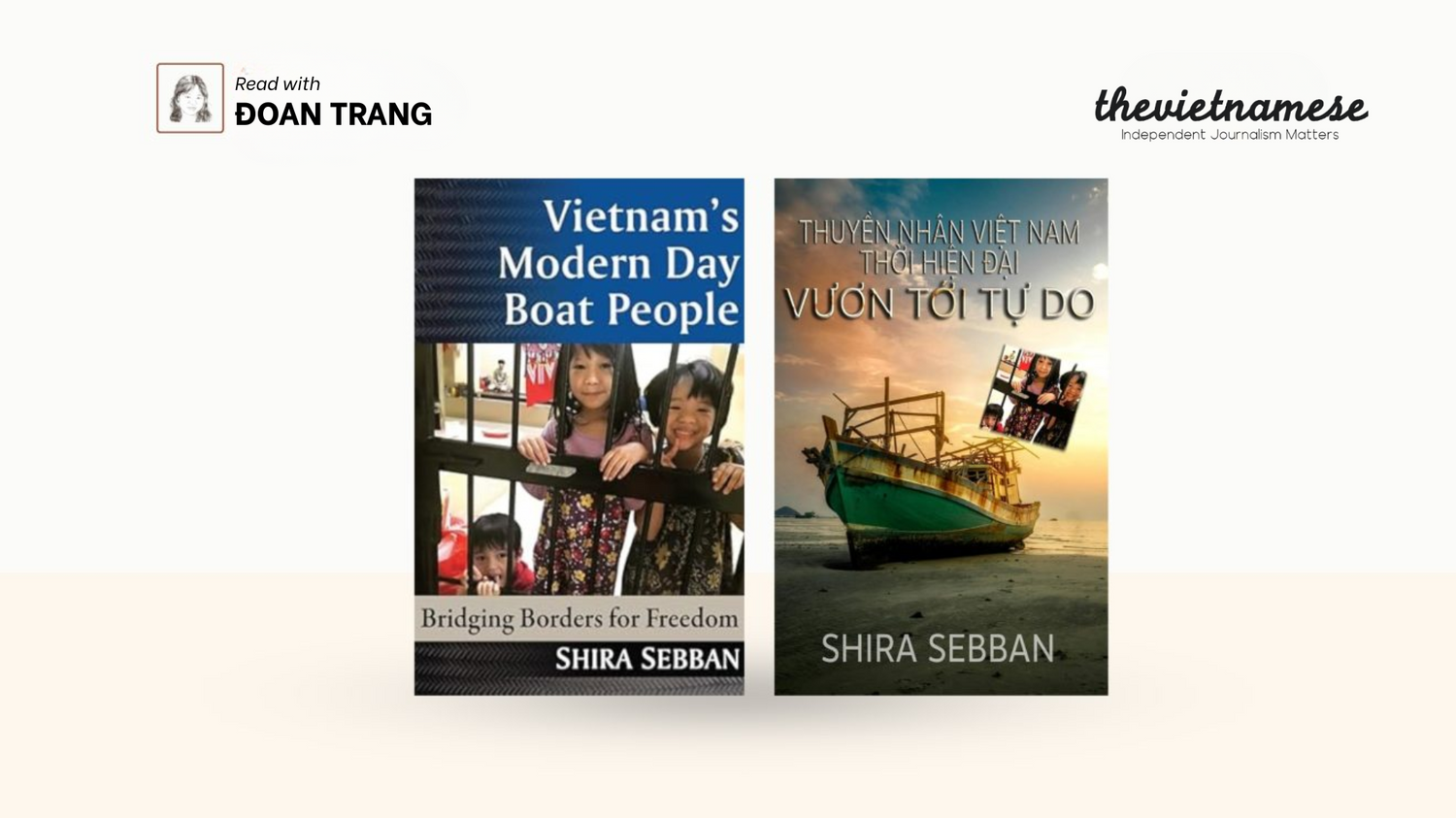

The term “boat people” may evoke a painful chapter from Việt Nam’s 20th-century history, yet few realize that the phrase still describes harrowing, modern-day tragedies. Shira Sebban’s 2023 book, Việt Nam’s Modern Day Boat People: Bridging Borders for Freedom, is a deeply humanistic work that sheds light on this ongoing issue. Its author—an Australian journalist, immigration specialist, and the descendant of Jewish refugees—brings a unique and empathetic perspective to the subject.

The book recounts the true stories of Vietnamese families who risked everything to cross the sea in search of freedom, and the volunteers who helped steer them toward a new future. Behind these turbulent voyages lies their yearning for freedom and extraordinary courage. At the same time, their stories serve as raw documentation of Việt Nam’s human rights realities, where many are forced to gamble with their lives. And yet, amid the desperation, Sebban’s work also finds glimmers of compassion and transnational solidarity.

The Story of Trần Thị Thanh Loan

Shira Sebban’s cause was sparked by a 2016 Australian media report about four children at risk of being sent to an orphanage after their parents were punished for attempting to flee Việt Nam. Their mother, along with dozens of other migrants, had spent a month at sea on a fishing boat hoping to claim asylum, only to be intercepted by the Australian navy and forcibly returned. The incident was particularly shocking, given that Australia had welcomed over 60,000 Vietnamese boat people in the previous century.

That mother, Trần Thị Thanh Loan, became the central figure in Sebban’s research. Loan cited three reasons her family sold everything to make their escape. First, as Catholics, her family endured ongoing religious discrimination. Second, the government arbitrarily confiscated their land without compensation. Finally, after losing their land and livelihood, her fisherman husband was attacked and robbed by Chinese naval forces in the South China Sea.

With no end to their suffering in sight, the family fled. But after their deportation, despite assurances from Vietnamese authorities that they would not be punished, both Loan and her husband were arrested and sentenced for illegally leaving the country. The two main breadwinners were imprisoned, and the now-homeless family was fined nearly 300 million đồng (~$13,000 USD). Their four children were left facing the threat of being sent to an orphanage, a government response that blatantly violated international commitments.

The Second Escape

Had Trần Thị Thanh Loan successfully settled in Australia, she might one day have been welcomed back to Việt Nam as a patriotic overseas Vietnamese. But because her journey failed, she was branded a criminal. This stands in stark contrast to international law, as the right to seek asylum is enshrined in Article 14 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and guaranteed by the 1951 Refugee Convention, along with its 1967 Protocol.

Moved by Loan’s ordeal, Shira Sebban took action. She launched a social media fundraiser to ensure that Loan’s children could continue their education, drawing support from former Vietnamese boat people—survivors of the 20th-century exodus.

Another ally emerged in Võ An Đôn, a lawyer who had been disbarred for defending land rights petitioners and imprisoned border crossers, who helped connect victims like Loan with Sebban.

Despite receiving no leniency at her trial, Loan’s sentence was postponed for a year due to international pressure, allowing her to care for her children. In that time, she made a bold decision: to secretly attempt a second escape, this time taking her four children with her. Her resolve was unshakable—it was better to die on the sea of freedom than to live imprisoned, physically or spiritually, in her homeland.

Loan’s second escape led her and her children to Indonesia, where many refugees face long-term detention in prison-like facilities. However, her case stood apart. The UNHCR office in Jakarta granted her family refugee status in record time, a swiftness Shira Sebban attributed to the very real threat of retaliation they faced in Việt Nam. It also served as a damning contrast to Australia’s careless handling of their initial asylum claim; even as it celebrated its anti-human trafficking efforts, Sebban realized that Australia’s rigid and inhumane asylum policies were harming the very people they claimed to protect.

Still, the family faced years of waiting for resettlement, a period prolonged by the COVID-19 pandemic. As doors in developed countries narrowed, Sebban and her volunteer network continued their tireless support. Finally, in 2022—six years after their first escape attempt—Canada accepted Loan’s family.

Together with translators, lawyers, and activists, her group accomplished what governments would not, or could not, be bothered to do. Reflecting on the ordeal, Shira Sebban remarked bitterly: “It may take a village to raise a child, but in our experience, it takes a global network to support a refugee.”

A Lighthouse in a Storm of Injustice

The stories of these modern-day boat people reveal a deeper truth: they were driven not primarily by poverty, but by persecution. They were imprisoned for the act of seeking freedom from a state whose actions they deemed unjust and arbitrary. As the book was going to press, Trần Thị Thanh Loan’s family was on the verge of becoming Canadian citizens—a milestone that came only after an exhausting, years-long effort from both her family and those who believed in justice and human decency.

In this way, the book serves as a lighthouse, illuminating international refugee law, advocacy, and the power of compassion that transcends borders. But while Loan’s story ends on a hopeful note, it remains a painful reminder: nearly 50 years after the original “boat people” crisis shocked the world, people in the 21st century are still risking death at sea in search of freedom.

Loan’s journey may be over, but others may still lie ahead. And so, haunting questions remain: If people still had hope of living with dignity at home, would they ever choose to face death at sea? And why is it that the ones who defend them are not their own government?