Time is running out for the United States to have a voice in managing deep-sea mining. The International Seabed Authority (ISA) will soon meet to advance the commercial framework regulating the mining of metals essential for the clean energy transition, aiming for adoption next year.

At a recent briefing for US congressional staff titled “Deep Sea Mining: Policy Implications for the United States” that I moderated at the US-Asia Institute in Washington, a group of experts weighed in on Washington’s opportunities and responsibilities in addressing the climate crisis through mineral extraction to power the transition from fossil fuels to green energy.

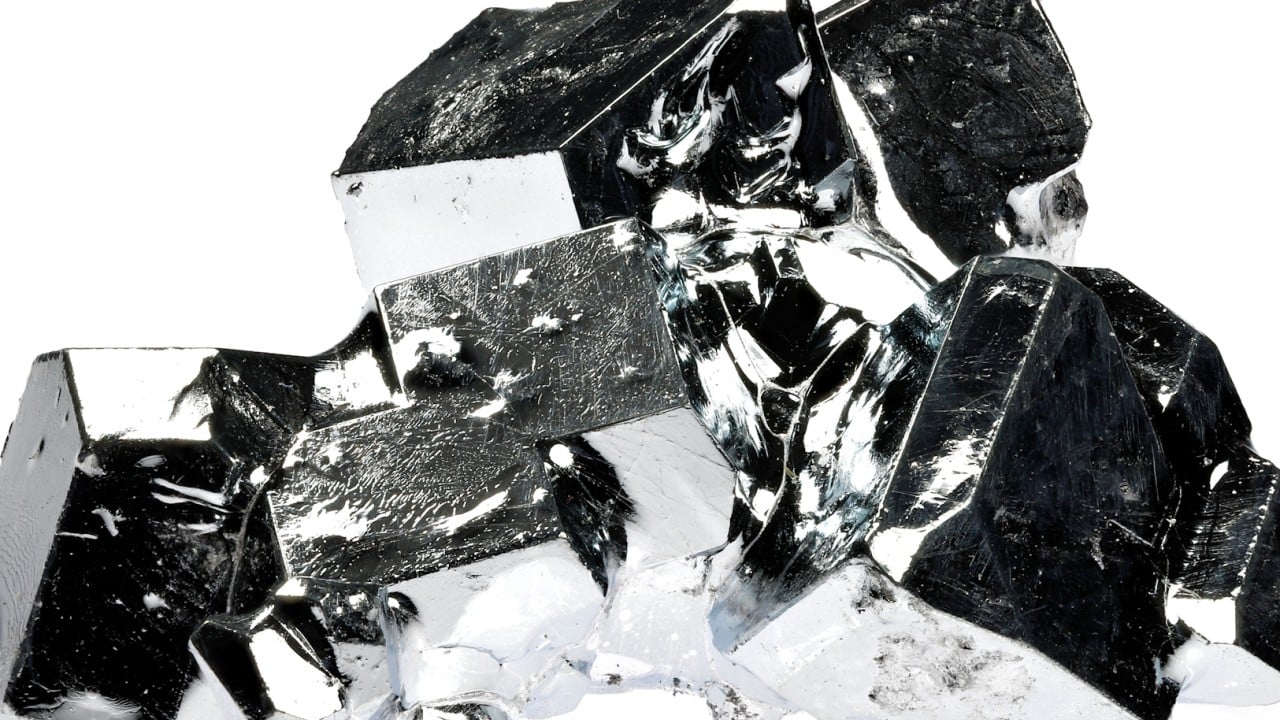

There is much at stake lying on the bottom of the sea floor for resource scarcity and demand. Critical minerals such as cobalt, nickel, manganese and rare earth elements are essential for modern technologies, including smartphones, electric vehicles and renewable energy systems.

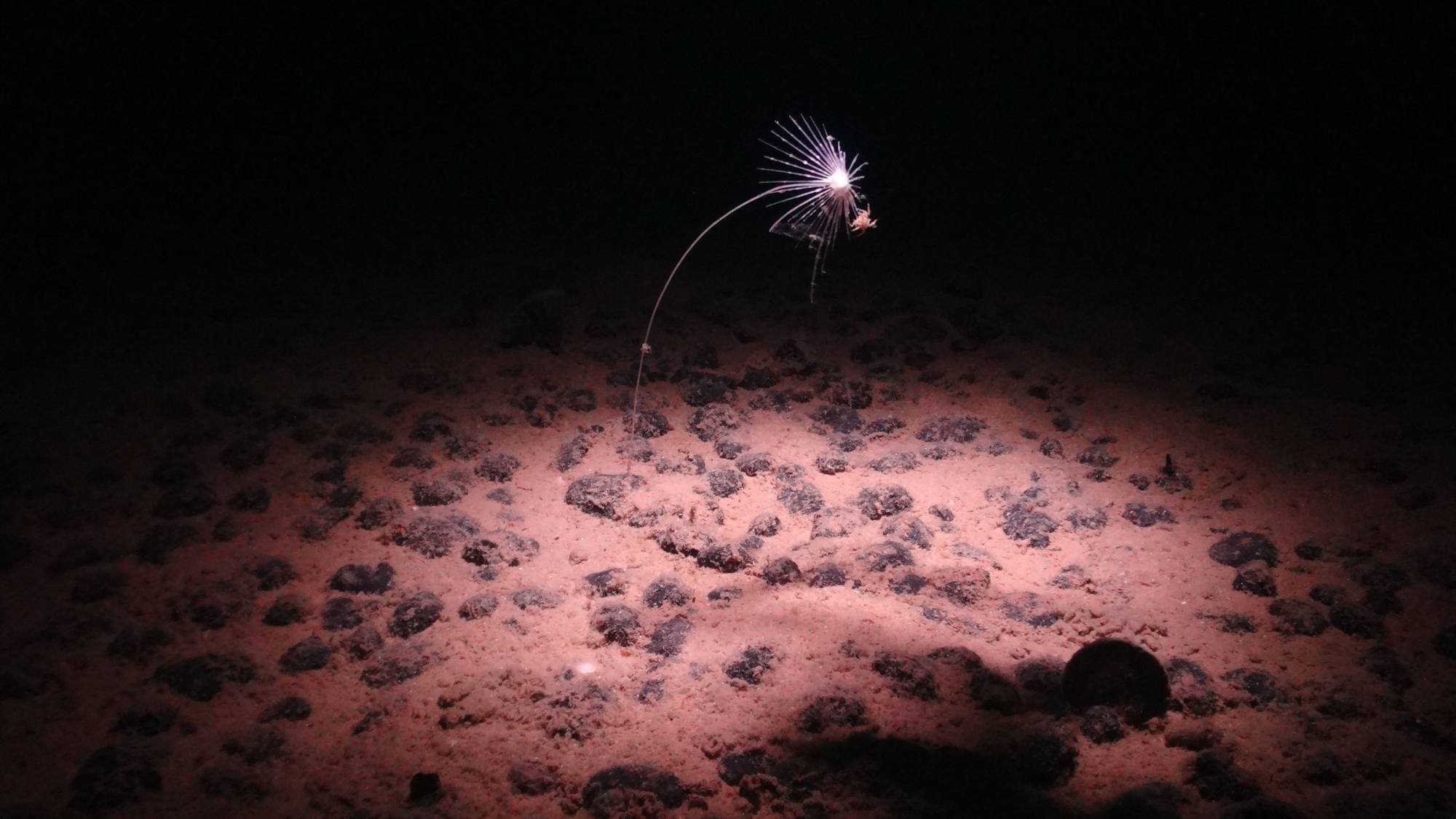

These minerals are present in nodules concentrated in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which spans more than 4.5 million sq km (1.7 million square miles) of the Pacific Ocean and which has become the focus of mining efforts.

The US is dependent on its allies and partners for securing access to seabed minerals; this is linked to its non-participation in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos). Without ratifying the treaty, it has no direct route to asserting its rights or taking part in international seabed mining activities governed by the ISA.

Consequently, to gain access to the rich mineral resources on the ocean floor, the US must depend on collaborative ventures with countries that are signatories to Unclos and have the requisite legal entitlements and operational capabilities.

Strategic partnerships with allied nations who possess advanced maritime technologies and robust frameworks for marine resource management not only provide the US with access to seabed minerals but also align with broader geopolitical and economic interests. By fostering partnerships with these countries, the US can leverage their legal access, technological expertise and operational infrastructure to jointly explore and exploit seabed minerals.

This cooperation ensures the US remains competitive in the global race for critical minerals. Moreover, these alliances reinforce diplomatic ties and enhance collective security as the strategic control of seabed resources becomes increasingly pivotal in global power dynamics.

The future of the US and its national interests depends on access to more than just elements critical to the renewable energy transition. A broader array of strategic mineral production and processing is crucial for national defence, advanced energy and telecommunications platforms, among other sectors.

The US does not need to rely on China’s supply chain for critical minerals. Long-standing Western allies such as Japan and South Korea can provide opportunities for primary processing, granting access to high-value commercial intermediates for refining.

The chances of Unclos being ratified in the US Congress remain slim. Nevertheless, the Biden administration has pledged to collaborate with allies to develop agreements and encourage partner nations to become producers of strategic and critical minerals to support US supply chain needs.

For example, the US and Japan signed an agreement last year to strengthen critical mineral supply chains. Japan has reduced its reliance on China for rare earths and continues to diversify its critical mineral sources, drawing on its experience in deep-sea mining research, exploration and technology development. It is now moving towards commercial extraction of minerals in its national waters.

The 70-year alliance between the US and South Korea presents an opportunity for enhanced cooperation in deep-sea mining. South Korea has been involved in deep-sea mining since the 1980s and is well positioned to support private sector participation in this field.

Having supported Europe’s natural gas demands following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Norway is no stranger to operating offshore. Earlier this year, the country’s parliament voted to approve a government proposal to open a vast ocean area for commercial-scale deep-sea mining.

My fellow panellists at the US-Asia Institute briefing reinforced my understanding of Washington’s pressing need to address the strategic mineral supply chain. This urgency is highlighted in a proposed US House of Representatives resolution calling on the ISA to adopt regulations permitting the collection of critical minerals from the international seabed area, which would enable the US to regain reliable and responsible supply chains.

Panellist Kristin Hengstebeck, director of business development and market research for Canada’s The Metals Company, said that innovations in nodule collection technology in the past 50 years had advanced deep ocean engineering, robotics and data acquisition, establishing the West as a leader in innovation.

The demand for critical minerals is expected to rise amid the rapid expansion of battery-powered technology and renewable energy systems. Estimates vary, but many forecasts suggest a substantial increase in the need for minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earth elements. For instance, the International Energy Agency projects that demand for nickel and cobalt could grow by an order of magnitude or more by 2040, driven largely by production of electric vehicles.

While it is true that all forms of mining have effects on the ecosystem, environmental opposition to mineral extraction often emphasises emotion rather than scientific data. With science taking the lead, the US can rely on its trusted allies to establish and implement responsible and sustainable deep-sea mining practices despite its current inability to set the rules itself.

James Borton is a non-resident senior fellow at Johns Hopkins/SAIS Foreign Policy Institute and the author of “Dispatches from the South China Sea: Navigating to Common Ground”