In August 2019, then US president Donald Trump made headlines with his surprising proposal to buy Greenland from Denmark. While the idea was met with scepticism and humour, it also reignited a historical debate and shed light on Greenland’s growing geopolitical significance.

Advertisement

As Trump prepares to re-enter the White House, his renewed interest in Greenland – and its implications for US foreign policy and Arctic governance – merits deeper examination.

The idea is not new. In 1868, US secretary of state William H. Seward, fresh from acquiring Alaska, expressed interest in Greenland and Iceland as part of America’s expansion strategy. In 1946, the Truman administration offered Denmark US$100 million in gold for Greenland, recognising its strategic importance with a Cold War emerging. While Denmark declined, the US was allowed to establish military bases on Greenland, including at Pituffik (formerly Thule), which remains a critical part of its Arctic strategy.

Greenland’s appeal lies in its immense natural resources, including rare earth minerals, and oil and gas reserves, as well as its strategic location between North America and Europe. As climate change accelerates Arctic ice melt, opening up new shipping routes and resource extraction opportunities, Greenland’s geopolitical value has soared. Trump’s interest in Greenland reflects a long-standing recognition of its importance in global affairs.

Under international law, the notion of buying Greenland raises complex questions. Greenland is an autonomous territory within the kingdom of Denmark. While Denmark retains control over foreign affairs and defence, Greenland’s government manages its internal affairs and has the right to pursue full independence through a referendum.

Advertisement

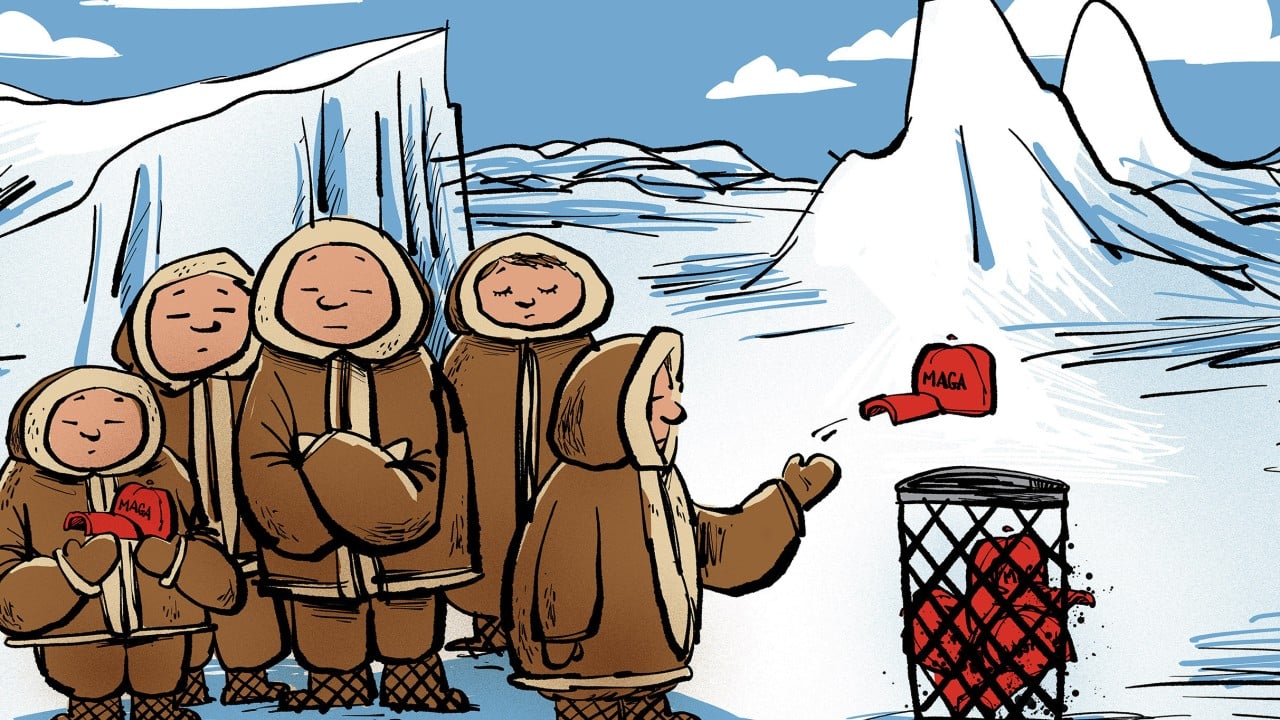

Buying Greenland would require the consent of both Denmark and Greenland’s governments. The transaction is likely to involve negotiations under international treaties and the United Nations Charter, which upholds the principle of self-determination. Greenland’s population of roughly 56,000 – predominantly indigenous Inuit – would need to be consulted, ensuring their rights and interests are protected.