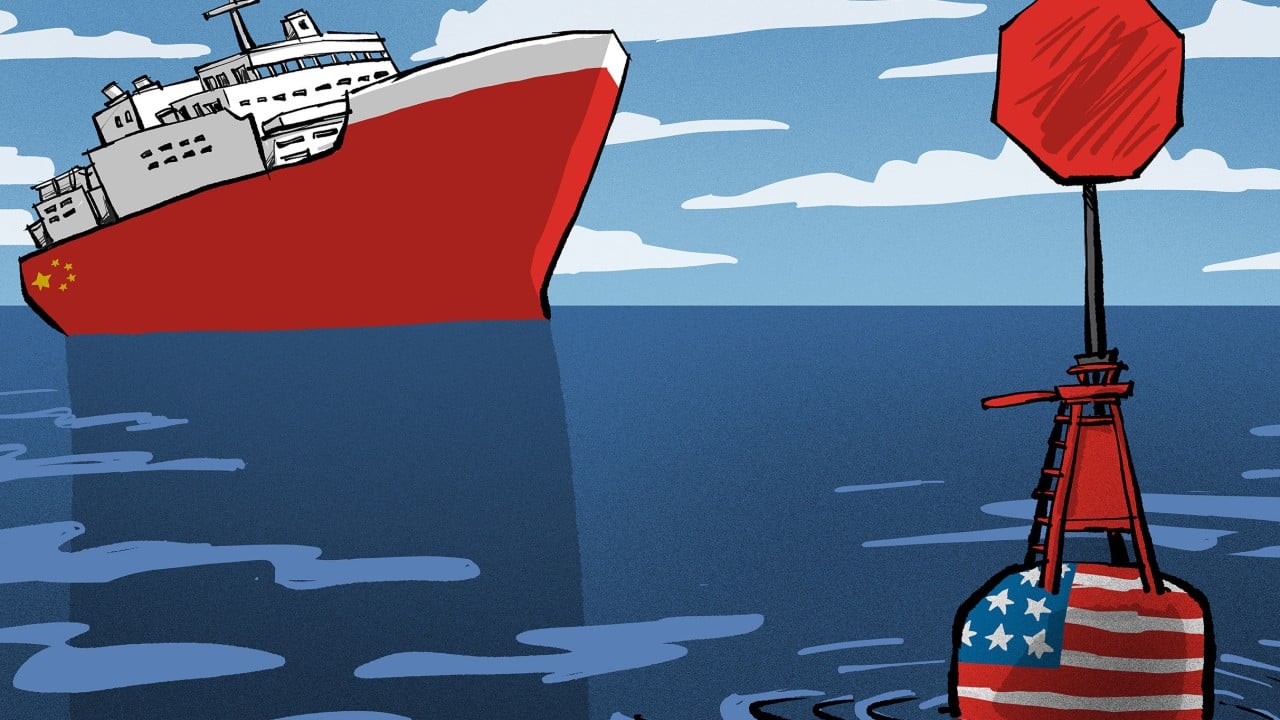

Last month, the United States coastguard “detected and responded to” the Chinese research vessel Xue Long 2 around 290 nautical miles north of Utqiagvik, Alaska. The US said the vessel was sailing within its “extended continental shelf” and implied the Chinese operation was engaged in “malign state activity”.

Advertisement

This reveals troubling inconsistencies in the US’ approach towards international maritime law, raising serious doubts about Washington’s commitment to the rules-based international order it so frequently claims to champion.

According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos), waters beyond 200 nautical miles fall under the legal regime of the high seas. Article 87 of Unclos guarantees all states the freedom of navigation and marine scientific research in these areas.

The Xue Long 2, designed for polar research, was operating in accordance with this principle. Yet, the US, by invoking national security and treating the vessel as a threat, seeks to shift the burden onto China to justify lawful conduct.

In 2019, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea reaffirmed that even non-physical interference with freedom of navigation or scientific research can constitute a breach of international law. The US’ response to the Xue Long 2 is not just an isolated legal overreach but a symptom of a broader strategic posture that prioritises political expediency over legal consistency.

Advertisement

Unclos permits states and competent international organisations to conduct marine scientific research on the high seas and in “the Area” – which can be understood as the international seabed beyond national jurisdictions. Moreover, the convention makes clear that a coastal state’s rights over the continental shelf shall not infringe upon other states’ freedoms.