Hiếu Mạnh wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on July 23, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.

Vietnamese citizens spent 6.51 USD billion on lottery tickets in 2024—a figure nearly equivalent to the state budget allocated to the Ministry of Public Security for 2025. Yet, this staggering revenue is built on the backs of hundreds of thousands of informal lottery ticket vendors who live precarious lives.

As ticket sales increase year after year, these vendors work with stagnant commission rates, no labor contracts, no health insurance, and no access to a social safety net. This creates a stark contrast at the heart of Việt Nam’s “gamble economy”: immense state profits generated by a vulnerable workforce, and overlooked inequities that shadow its success.

A $6.5 Billion Industry Fueled by Everyday Gamblers

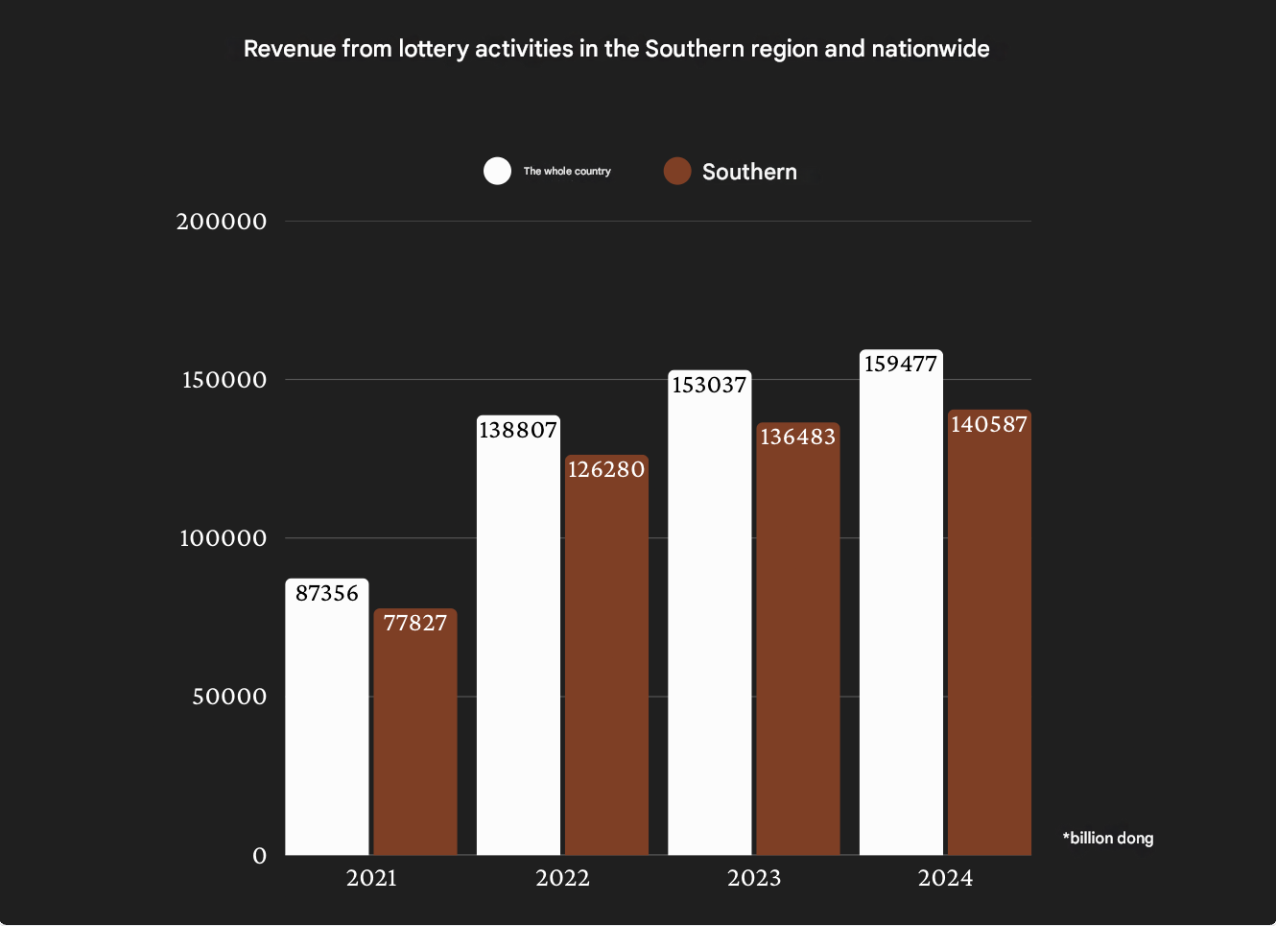

In 2024, total revenue from lottery operations across Việt Nam reached 159.477 trillion đồng —around 6.51 billion USD. To put that figure in perspective, it is more than 35 times the total revenue of the country’s entire publishing industry in the same year.

This massive industry is also a significant contributor to the state budget. From 2020 to 2024, the lottery system added over 206 trillion đồng to state coffers, accounting for roughly 2.5% of national revenue and growing by about 10% each year. This growth shows no signs of slowing; in the first quarter of 2025 alone, lottery revenues in Southern Việt Nam totaled 38.55 trillion đồng, putting the industry on pace for another record-breaking year.

The Primary Revenue Stream for Some Southern Provinces

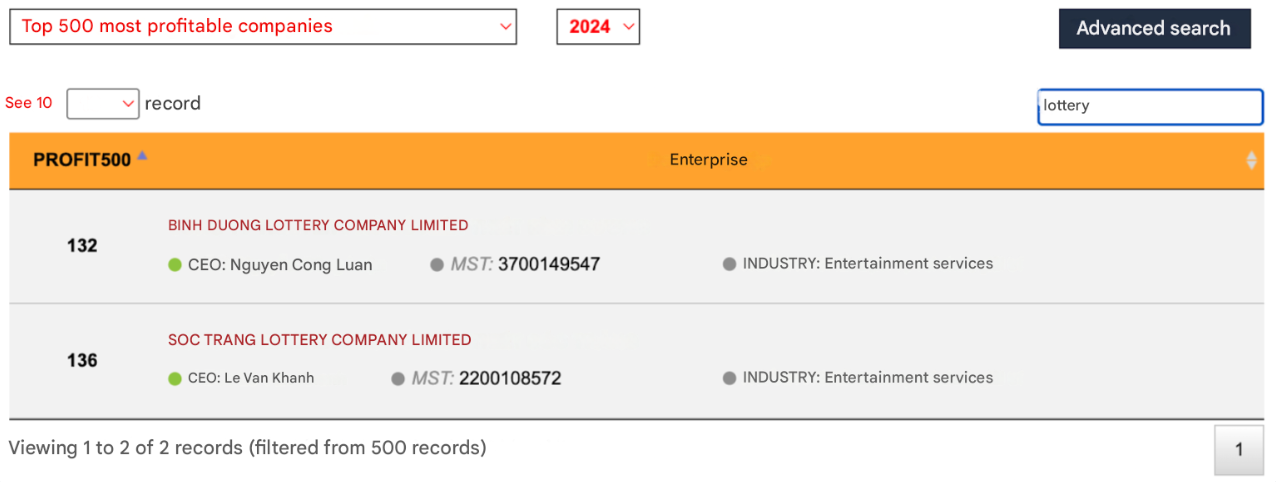

Việt Nam’s lottery companies are structured as state-owned enterprises under the direct control of provincial or city People’s Committees. Though they operate locally, their reach often spans multiple areas, allowing them to generate trillions of đồng in revenue and become significant contributors to local budgets, particularly in the South. In 2024, each southern province had between 4,000 to 6,000 vendors on average. According to the Vietnam Report, Southern Việt Nam is home to 21 lottery companies, and they consistently rank among the country’s 500 largest enterprises by revenue.

For some provinces, this lottery income is a financial lifeline. In 2024, the Sóc Trăng Lottery Company contributed 2.162 trillion đồng to the provincial budget, accounting for a staggering 40% of Sóc Trăng’s total state revenue that year. Similarly, the Cần Thơ Lottery Company contributed 1.98 trillion đồng, making up 11% of the city’s budget.

Perhaps the most striking example comes from Bạc Liêu province, where in 2019, its lottery company generated more revenue ( 4.466 trillion đồng) than the entire province collected in state revenue (3.183 trillion đồng).

The Harsh Reality for Việt Nam’s Street Lottery Vendors

Despite the lottery industry contributing tens of trillions to public coffers, the hundreds of thousands of informal street vendors who power it remain largely excluded from its benefits.

This large and growing workforce—from 300,000 in 2012 to an estimated 500,000 by 2022—is composed of some of the most vulnerable people in Việt Nam: the elderly or disabled. They work without labor contracts, health insurance, or any social safety net. A proposal by one lottery company to purchase health insurance for vendors was even rejected by the Ministry of Finance, citing regulatory prohibitions.

As the industry expands, the vendors’ situation remains stagnant. The Ministry of Finance approved increases in the number of lottery tickets issued in October 2024 and June 2025, boosting potential revenue for the state companies, but not for the vendors.

As Nguyễn Hồng Cẩm, a vendor in Cà Mau, shared:

“Since the increase in ticket volumes, I’m still only allowed 200 tickets a day by the agency. On good days, I sell out. But if it rains or sales are slow, I’m stuck with unsold tickets I can’t return. If I try to return them, the agency reduces my daily quota below 200. And now, with more vendors out there, it’s getting harder to sell.”

While the Southern Lottery Council has issued directives requiring agents to accept returns, the system pushes the risk downward. Agents who accept too many returns may receive fewer tickets in the future, so they pressure the vendors instead.

The numbers reveal a precarious existence: a vendor receives 200 tickets a day to be sold at 10, 000 đồng. With a 10-12% commission, they can earn up to 240,000 đồng daily, but being unable to sell just 20 tickets results in a net loss, as they must absorb the cost themselves.

A Stark Divide in Income

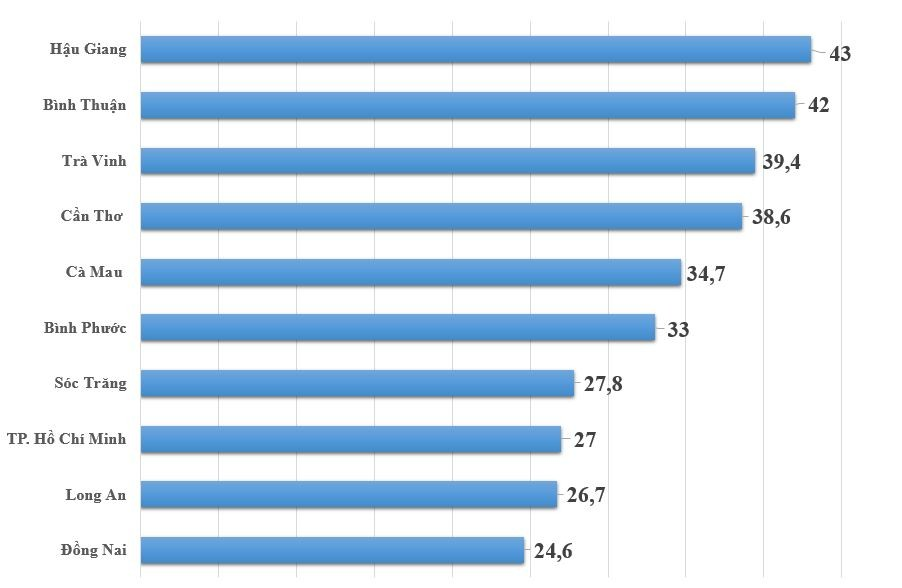

While street vendors struggle to make ends meet, employees in state-run lottery companies earn enviable salaries.

In 2023:

- Workers at the Hậu Giang Lottery Company earned a monthly average of 43 million đồng

- Workers at the Bình Phước Lottery Company earned about 33 million đồng a month

Big Money, But Where Is the Development?

The industry’s official name has long been “xổ số kiến thiết” — “lottery for development”—suggesting public benefit as its core mission. The massive revenue numbers might suggest it’s delivering on that promise.

But in reality, the people who power this machine, both the vendors and the buyers, are largely low-income earners who give much and get little in return. For many buyers, the small daily gamble represents a significant portion of their limited income, an “investment” with no guaranteed return.

Meanwhile, persistent concerns about how lottery revenues are spent undermine the “development” narrative. In 2024, news that the Sóc Trăng Lottery Company organized a lavish “study trip” to Malaysia and Singapore for its staff sparked public backlash and raised questions about priorities and accountability.

Beyond individual cases, experts have warned that over-reliance on lottery revenues may distort local economies, undermining incentives to develop more sustainable industries.

Việt Nam’s lottery sector is, by all measures, booming. It funds provincial budgets and generates billion-dollar revenues. But at its heart are the poor—those who sell the tickets and those who buy them—receiving little of the windfall their labor and hope generate.