In Tuanjie Village, in the heart of Chongqing – China’s largest inland city, best known for its spicy hotpot – orange gantry cranes hoist cargo onto goods trains bound for Europe and Russia. Each day, hundreds of containers pass through the sprawling 82,000-square-metre yard, exporting electric vehicles and components or returning with cars, meat, wine and dairy.

Advertisement

Just a five-minute drive away, blue cranes mark another yard – this one unloading tropical fruits and raw materials from Southeast Asia.

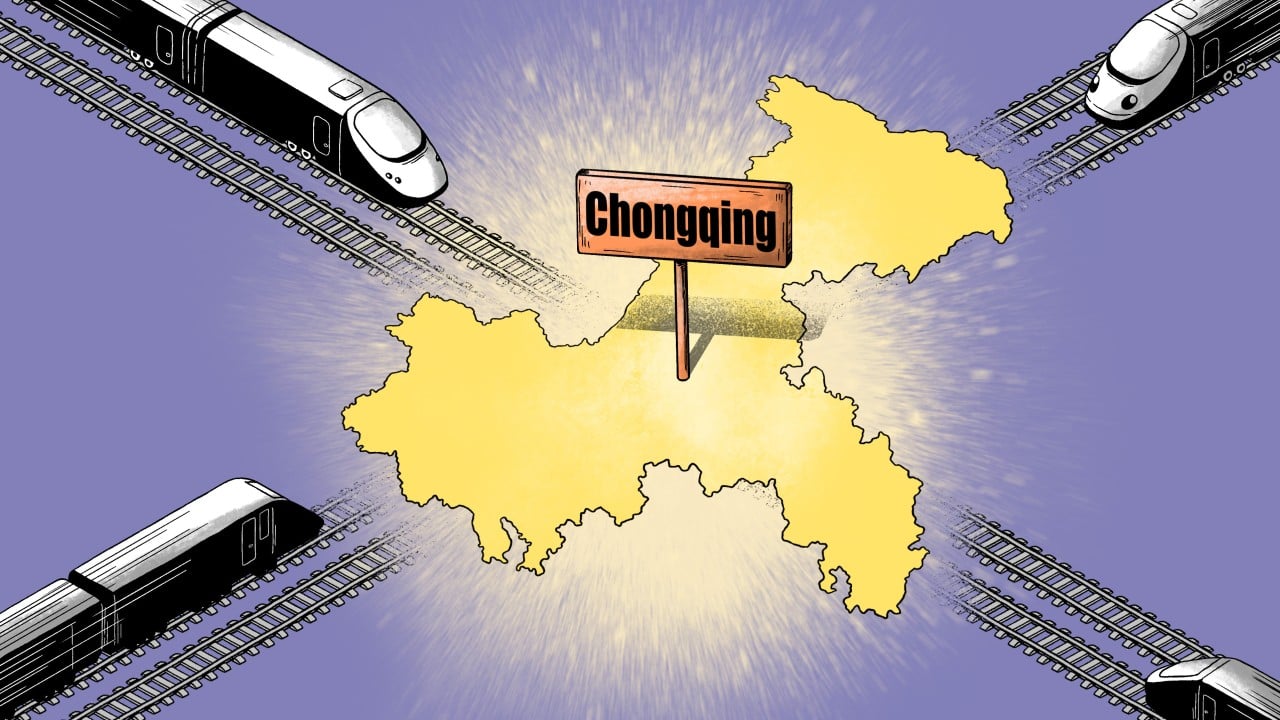

Over the past decade, the southwestern Chinese metropolis has evolved into a hub of international trade, thanks to the launch of two expansive cross-border rail networks. One runs west to Germany and the other extends south, reaching as far as Singapore – trade corridors that give China faster, more reliable access to global markets while offering other countries a clear route into its vast interior.

But the city’s ambitions go beyond simply doing business with foreign partners. It aspires to become a central node in the global economy through which other countries trade – a rail-based “Suez Canal”, connecting Asia and Europe.

The changes under way in Chongqing could offer a snapshot of how the world’s second-largest economy is deepening its global trade footprint amid rising geopolitical risks, including the possibility of a complete decoupling from the United States.

Advertisement

“Shipping goods from Asean to Europe via Chongqing by rail is 10 to 20 days faster than traditional sea transport,” said Liu Yizhen, vice general manager of the New Land-Sea Corridor Operation Company, which is in charge of the freight route from Chongqing to Southeast Asia.

The debut train on the fast track route, named the Asean Express, launched in October last year. It departed from Hanoi, Vietnam, and took five days to reach Chongqing, where its wagons were briefly reorganised before continuing for another two weeks to its final destination in Malaszewicze, Poland.