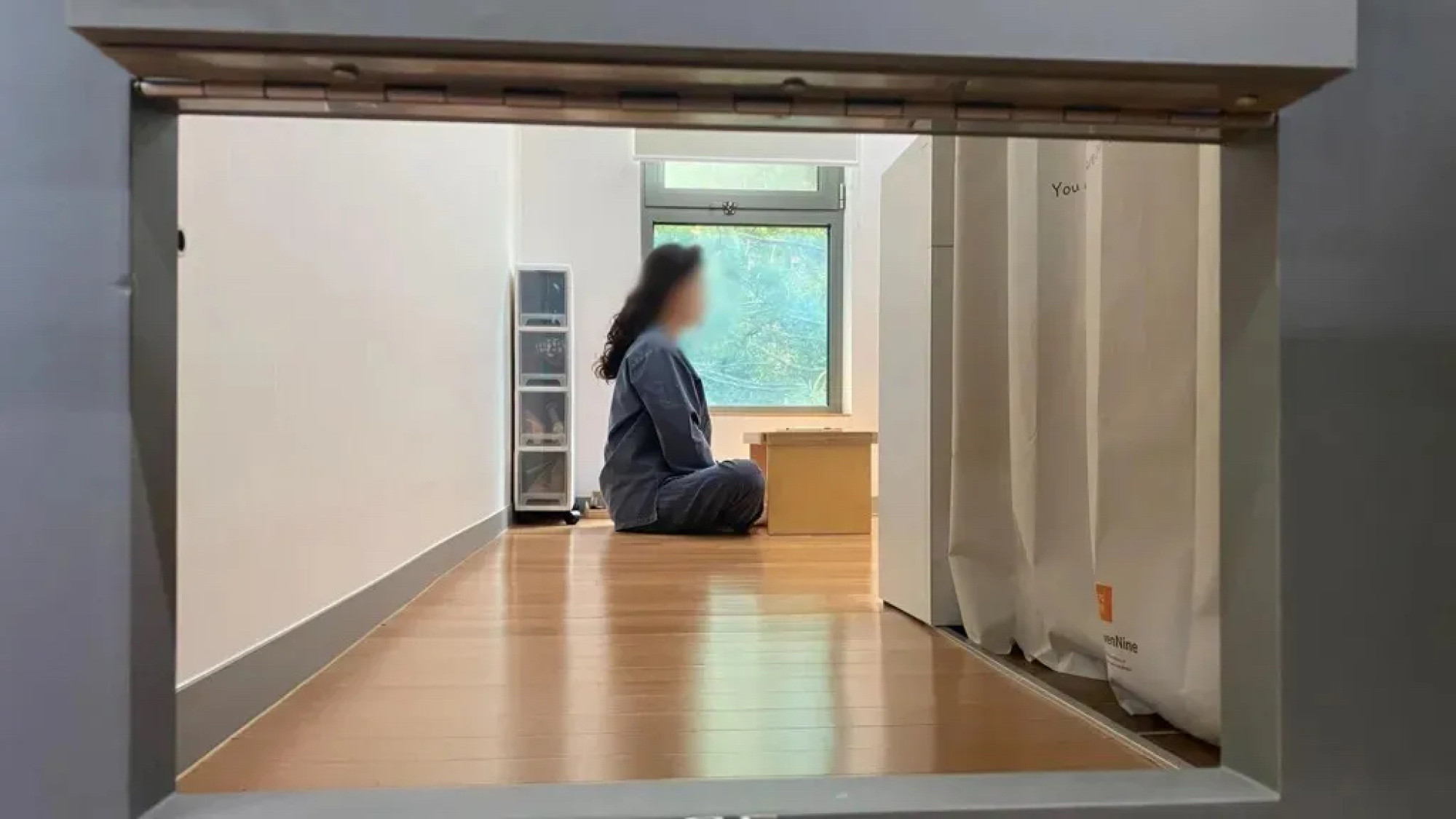

Parents in South Korea are choosing to confine themselves to a room for three days to experience the social isolation and anxiety their children are suffering.

At a “Happiness Factory” in the country’s northeastern Gangwon province, mothers and fathers are attempting to understand the secluded inner worlds of so-called “reclusive youths” so they can help them.

Such children have withdrawn from society and spend most days isolated, avoiding communication and usually staying in their bedrooms.

The confinement experience for parents is part of South Korea’s Isolated Youth Parent Education Programme, which spans 13 weeks and is operated by the Blue Whale Recovery Centre and the Korea Youth Foundation.

Residents stay in single bedrooms with bare walls and are forbidden to use electronic devices. Their only link to the outside world is a hole in the door for food delivery.

Help for parents includes mental health talks that focus on family, parent-child relationships and how people connect to the world.

Some participants say that they have begun to better understand the anxiety and loneliness of their children.

Jin Young-hae, a 50-year-old mother, told BBC Korea that her son has isolated himself in his bedroom for three years.

After dropping out of college, he locked himself in his room, began neglecting his personal hygiene and refusing meals.

“My heart is broken,” she said.

Jin said that after her three-day confinement and reading the diaries of other reclusive youths, she has developed a better understanding of her 24-year-old son’s emotions.

“I realised he is using silence to protect himself because he feels no one understands him,” said Jin.

Yoo Seung-chul, a communication and sociology professor from Ewha Womans University in South Korea told the Post that the experience of emotional imprisonment for parents is a form of perspective-taking that can encourage open communication between parents and children.

“However, this programme still requires ongoing support from mental health professionals to truly improve the current trend of social withdrawal among young people,” he said.

Last year, a South Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare survey of 15,000 young people found that more than five per cent of respondents were isolating themselves.

Their life satisfaction and mental health levels were significantly lower than their peers.

Kim Seonga, a researcher at the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs, suggests that reclusive South Korean youths are like those in China’s “lying flat” movement.

They are young people who have given up trying to integrate into society.

Research indicates that young South Koreans are isolating due to work pressures, emotional issues and family demands.

Kim Hye-won, a psychology professor of Hoseo University in the city of Cheonan said that South Korean youth strive to follow a traditional life path.

This includes finding work in their 20s, marrying in their 30s and having children in their 40s.

Deviating from this path can make them feel worthless, resulting in frustration, shame and withdrawal.

Research shows that when young people become isolated, it has a significant effect on wider society.

The Korea Youth Foundation estimated last year that economic losses, as well as the cost of welfare and healthcare services for reclusive youth, could exceed 7.5 trillion Korean won (US$5.4 billion) annually.