Filipinos are increasingly being blocked from their traditional fishing grounds at Scarborough Shoal by Beijing’s enforcement of its territorial claims in the South China Sea, with new restrictions and aggressive patrolling creating a potential flashpoint over fishing rights and national sovereignty.

The New Masinloc Fishermen’s Association in the town of Masinloc in Zambales said its members had been unable to get closer to Scarborough Shoal ever since the Chinese coastguard began enforcing an anti-trespassing regulation on June 15.

“None from our group can go to Scarborough Shoal now. We tried several times, but the Chinese coastguard blocked our way, and then they will deploy their personnel on board rubber boats to drive us away. Maybe, if we insist on going there, they will arrest us,” Leonardo Cuaresma, the head of the association, told This Week in Asia on Wednesday.

There have been no reports so far of any arrests of Filipino fishermen since the regulation came into force.

Cuaresma said his fishermen had been severely affected by the regulation, noting how they now must fish 40 nautical miles (74km) from the shoal, where most of the fish in the area are. Before the regulation, big fishing boats could get up to 10 nautical miles from the shoal, while smaller boats could fish inside the lagoon.

He also accused the Chinese coastguard of destroying their fish aggregating device set up by the association’s members in Scarborough Shoal.

Under its anti-trespassing regulation, the China Coast Guard says it is authorised to detain foreign nationals for up to 60 days if they are caught trespassing in what it considers to be Beijing’s territorial waters, even if those waters are within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone.

“There are Philippine Coast Guard, but they are far from the shoal. Only the Chinese coastguard and their militias are there,” Cuaresma said.

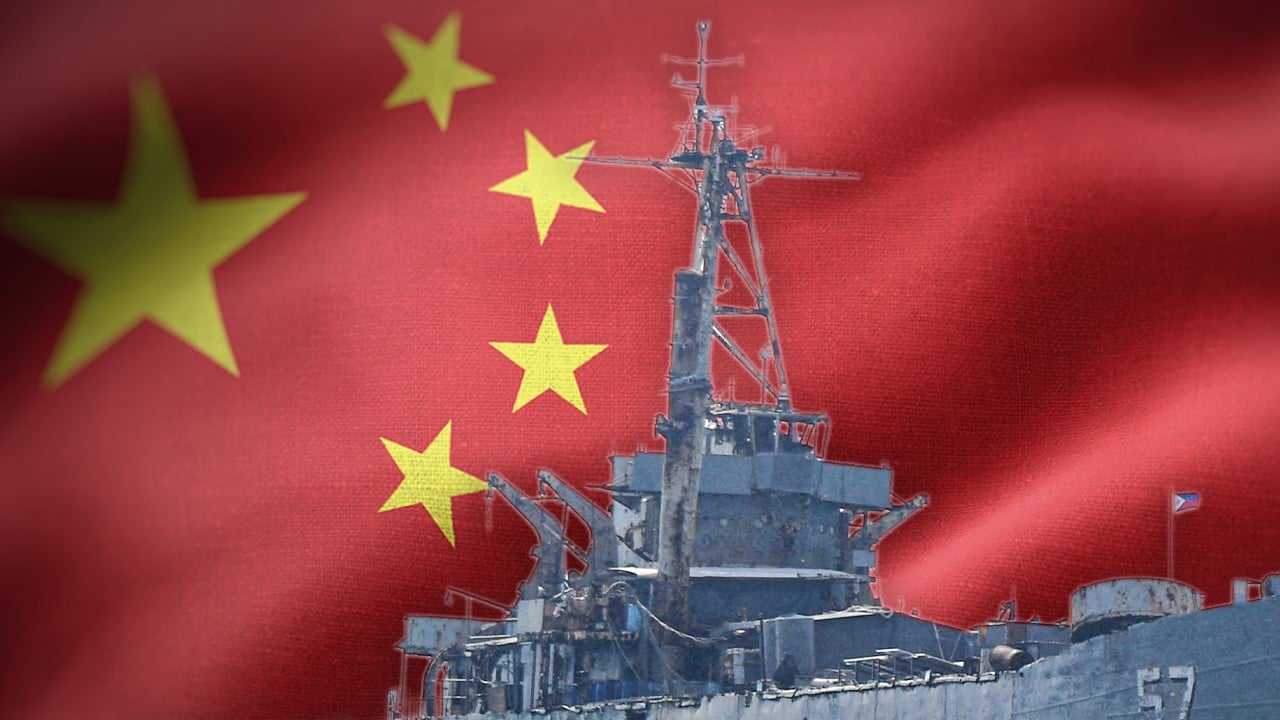

Scarborough Shoal – a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks in the middle of the West Philippine Sea – is a traditional fishing area for both countries. It is located about 120 nautical miles west of the Philippine island of Luzon and 594 nautical miles from China’s Hainan Island.

‘Occupation is ownership’

Jose Antonio Custodio, a defence analyst and fellow at the Consortium of Indo-Pacific Researchers, told This Week in Asia that issues in the West Philippine Sea always boil down to “occupation is ownership”.

In 2012, China seized Scarborough Shoal, the traditional fishing ground of Filipino fishermen within the 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone of the Philippines, after a two-month stand-off with the Philippine Navy.

Manila took Beijing to court after alleging that Chinese naval vessels obstructed the Philippines’ entry to Scarborough Shoal, which has since remained under China’s administrative control.

“We made a strategic mistake in 2012 after the Philippines withdrew from the Scarborough Shoal. That was the worst mistake the Philippines made. It should never have withdrawn and allowed the Chinese to consolidate,” Custodio said, adding that this had brought about the issues currently facing the fishermen.

In 2016, a UN arbitration court ruled in favour of the Philippines’ claims in the South China Sea, dismissing Beijing’s historical claims to the region – delineated then in Chinese maps by a nine-dash line (now a 10-dash line) – as invalid. However, Beijing rejected the ruling and has since insisted that it has jurisdiction over all areas within that boundary.

On Tuesday, Alexander Lopez, the newly appointed presidential palace spokesman for the National Maritime Council, said the government was pursuing diplomacy over military action in response to its increasingly tense maritime row with China.

However, Custodio said for Filipino fishermen to be able to freely fish in Scarborough Shoal, Manila should order the Philippine Coast Guard to escort the fishermen and face off with the Chinese.

The other way, he suggested, was to “have negotiation with the Chinese recognising their ownership in the area and there will be something in exchange for that, which is exactly what happened during the time of former president Rodrigo Duterte where he set aside the arbitral ruling”.

Duterte, known to be pro-China, affirmed the “importance of continuing” talks in solving the maritime dispute. During his six-year presidency, he worked to rebuild ties with Beijing that had frayed after the arbitral ruling in 2016.

Analyst Chester Cabalza, president of the Manila-based International Development and Security Cooperation, said the Philippines and China could still work to resolve the dilemma and come up with an agreement similar to the pact they made regarding the Second Thomas Shoal.

“The Philippines has the legal upper hand while China has the military might in the contested large atoll near Zambales,” Cabalza told This Week in Asia.

Manila also had the “moral ascendancy to assert its sovereignty in Scarborough Shoal” which was within its exclusive economic zone, he said, adding that the shoal was a factor in the 2016 arbitral ruling being decided in favour of the Philippines.

Don McLain Gill, a geopolitical analyst and lecturer at the Department of International Studies at De La Salle University, said Beijing had been imposing an illegal de facto exclusionary policy since it occupied Scarborough Shoal in 2012.

Gill said this was done through the illegal and provocative measures of the Chinese coastguard and called on Manila to take steps to “delegitimise” their actions in the contested sea.