The Philippines is looking to diversify its infrastructure funding through allies such as the US and Japan after what analysts say is a withdrawal of several China-backed projects in the Southeast Asian country over geopolitical reasons.

On July 26, the Philippine transport department said funding for a feasibility study on the Subic-Clark-Manila-Batangas railway was in the works. The railway project is a joint initiative by the Philippines, Japan, the United States, Sweden and the Asian Development Bank.

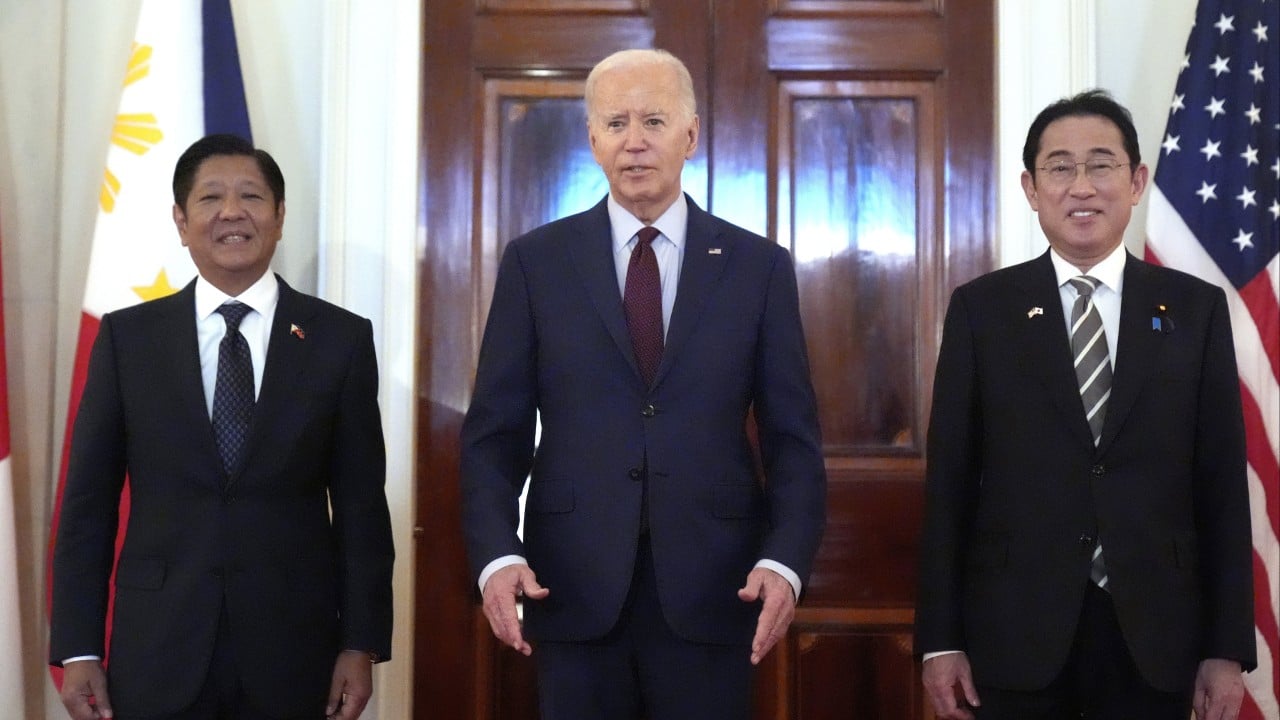

The 250km project is part of the proposed Luzon Economic Corridor, announced during the trilateral leaders’ summit in April attended by Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos Jnr, US President Joe Biden and Japan Prime Minister Fumio Kishida.

Once completed, the project will run along and connect four cities on Luzon island, linking three main ports and two international airports.

The Subic-Clark-Manila-Batangas railway project is an updated initiative of the original Subic-Clark railway project that was initially backed by Chinese investments.

Nikkei Asia reported on Monday that officials from the Philippines’ Bases Conversion and Development Authority, the agency overseeing redevelopment projects in former US military bases such as Subic and Clark, were in Tokyo earlier in July to seek funds for the latest railway project, as well as other developments in the former bases.

The Philippines backed out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in October after Beijing became unresponsive to its funding requests for three railway projects. As a result, the projects under the initiative have been dropped.

China had initially pledged nearly US$5 billion of funding to build three railway lines in the country including the Subic-Clark railway project, the South Long Haul railway project in Luzon and the Mindanao railway project in southern Philippines.

The first phase of the Mindanao railway project, which costs 83 billion Philippine pesos (US$1.4 billion), was supposed to be set for construction in January 2019. Last year, the Philippines’ finance department wrote to the Chinese embassy and said Manila was “no longer inclined to pursue the Chinese ODA [official development assistance] financing for the Mindanao railway project.”

This followed comments from a senior Chinese economic official, who cited “geopolitical factors” for hindering funding of the Philippine projects.

Chester Cabalza, president of the International Development and Security Cooperation think tank, told This Week in Asia that China had “obviously backed out from the railway deal under the Belt and Road Initiative with the Philippines to isolate and punish the Marcos administration’s diplomatic and strategic rapprochement with the US”.

Although Chinese officials did not mention maritime disputes as a reason for the stalling in funding, Manila and Beijing have been at odds over the South China Sea for years, which intensified after former president Rodrigo Duterte, who was known for his pro-Beijing policies, left office in 2022.

Duterte claimed at the start of his presidency in 2016 that he had secured pledges of US$9 billion in official development assistance from Chinese companies for infrastructure projects. But the commitments had fizzled out by 2019 when Duterte was still president, according to media reports.

Dindo Manhit, president of think tank Stratbase ADR Institute, said the Marcos administration’s move to veer away from Chinese funding, particularly those under the Belt and Road Initiative, was a “calculated move” to ensure that the Philippines’ national interests were protected.

Manhit said that the loans under the Belt and Road Initiative could be viewed “as a form of economic coercion”. Previous projects such as the Kaliwa dam and Chico river pump irrigation projects were subject to higher interest rates compared with other financing sources and circumvented Philippine laws that could lead the country to a debt trap even without them materialising, Manhit added.

“By looking into other sources of funding, either through official development assistance or public-private partnership, the Philippines ensures the realisation of projects under terms that are deemed favourable to the Philippines,” he said.

The funding saga happened against the backdrop of China’s heightened assertiveness in the West Philippine Sea, Manhit said. He was referring to Manila’s term for a part of the South China Sea that includes its exclusive economic zone, where several clashes involving Chinese and Philippine vessels had happened in recent months, including one that led to a Filipino serviceman losing a thumb.

A June survey from Pulse Asia and Stratbase revealed that 95 per cent of Filipinos did not want the Marcos administration to work with China.

Matteo Piasentini, a geopolitical analyst and lecturer at the University of the Philippines’ political science department, said that it was difficult to say whether maritime disputes in the South China Sea were linked to the withdrawal of China-backed infrastructure projects.

China was relooking its Belt and Road Initiative while it took “strong political will” for recipient countries that have projects under the initiative to push for their completion, Piasentini said.

“Third, Belt and Road Initiative financing doesn’t happen in a vacuum: there are other countries that offer similar projects and compete with the Belt and Road Initiative,” he added.

Cabalza said Beijing has also reinvested in some projects under the Marcos administration’s infrastructure programme. Conversely, it made sense for the Philippines to partner with the US and Japan rather than to have a “short-lived and volatile economic dependency” on China as Beijing used economics to maximise its interests in the South China Sea, he added.

The Chinese pullback from the infrastructure projects is likely to have a limited impact on the Philippine economy, according to analysts.

Manhit cited data from the Philippine central bank that showed the top sources of foreign direct investment inflows in the Philippines in 2023 were Japan, the US, and Singapore, while China only accounted for 0.18 per cent of the total.

Meanwhile, analysts are optimistic about investments from the US and Japan, particularly the Luzon Economic Corridor, which can become a catalyst for economic growth.

“These investments are expected to enhance development in different sectors, focusing particularly on increasing critical infrastructure. Such initiatives are crucial for laying the foundation for larger investments,’ said Manhit.

The Philippines is strengthening its economic security by forging closer links with countries such as the US and Japan in infrastructure projects, according to Piasentini.

Cabalza said: “As the Philippines draws commercial interest from like-minded nations, this will widen its economic options and show to China that they cannot boss around the Philippines.”