A recent earthquake in Vanuatu, which cut off its internet for 10 days, highlighted the vulnerability of strategic Pacific communications infrastructure.

When a magnitude 7.3 earthquake struck Vanuatu in December, it not only caused widespread devastation and left at least a dozen people dead, but it also exposed a critical vulnerability in the country’s digital infrastructure, which is common across the Pacific: a lack of redundancy.

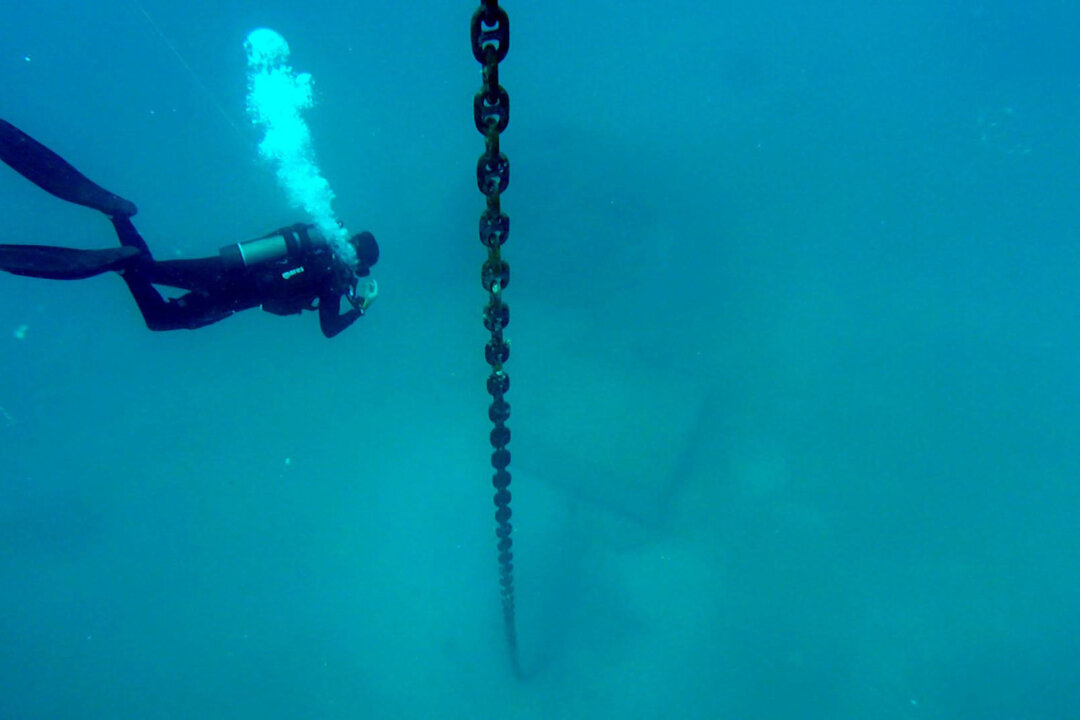

All of Vanuatu’s internet traffic is handled by a single undersea cable, ICN1. The Dec. 17 earthquake caused a fire at the cable landing station, disabling the power supply and cutting all internet traffic.

Only after what was described as “a multilateral effort under extreme conditions” was the connection restored in ten days.

The situation isn’t confined to Vanuatu—across the entire Pacific, critical digital infrastructure lacks redundancy.

Since at least the 2022 volcanic eruption in Tonga, which similarly disrupted communications across the Pacific, concerns have been raised about the need for a duplicate submarine cable system.

The governments of most Pacific countries recognise this but don’t have the funds to achieve it while also improving and maintaining critical local infrastructure such as healthcare, education, and transport.

Traditional geostationary satellite systems, sometimes touted as an alternative to undersea cables, lack bandwidth and incur high operational costs, so they are typically reserved for government, airlines, banking, and healthcare.

Low-Earth orbit satellites such as Starlink offer higher bandwidth and lower cost, but the network’s mix of both civilian and military users raises significant security and legal concerns.

Starlink’s involvement in conflicts such as the war in Ukraine means its satellites could be considered a legitimate target under international law, especially if its services become integral to military operations.

And it, too, could face bandwidth constraints as its user base grows, particularly in densely populated areas.

Unlike cables, which offer scalable infrastructure, Starlink’s network is constrained by the number of satellites in orbit and the number of users accessing the system at any one time.

Some projects are underway which, when completed, will fill some of the gaps. Vanuatu-based Interchange Group is working on implementing the TAMTAM system, the world’s first Science Monitoring and Reliable Telecommunications (SMART) cable set to connect Vanuatu to New Caledonia, a project contracted to Alcatel Submarine Networks.

Google has also proposed a third cable connecting Vanuatu to the broader Pacific network.

But a resilient backbone of redundant cable is still needed to link all Pacific nations to the rest of the world.Vanuatu’s government has advocated for a second cable since 2018 but says it doesn’t have the capital and is concerned that maintenance costs could raise telecommunications prices for the country’s already vulnerable population.

It’s just one of several countries in the region seen as key to combatting rising influence of the Chinese Communist Party. But while Western governments—including Australia and the United States—have acknowledged the need for increased investment, so far none has been forthcoming.

It’s an issue that needs to be urgently addressed, according to Cynthia Mehboob, a doctoral researcher based at the Department of International Relations at the Australian National University.

“This is where Australia has both an opportunity and a responsibility to make a meaningful contribution,” she wrote in a paper on Jan. 6.

“As the region’s closest and most influential neighbour, Canberra has an opportunity to step in, not [because] of geopolitical necessity, but as a genuine partner to safeguard Vanuatu’s communications infrastructure.

“Australia must also recognise that its geopolitical interventions in one Pacific Island country can have significant knock-on effects for commercial providers in others, complicating efforts to build resilient regional networks.”

She cited comments by Simon Fletcher, CEO of Vanuatu-based Interchange Group, that Australia’s intervention in the Solomon Islands Coral Sea Cable project had adversely impacted his company’s privately funded projects, posting on Twitter in 2018 that it was “very hard to compete with a free cable.”

But if Australia prioritises digital resilience and equitable collaboration, it can demonstrate its commitment to its “Pacific family,” Mehboob says. Ensuring that Pacific nations are better equipped to face future challenges will mean they don’t need to rely on “actors whose priorities may not always align with those of the country.”

“The 17 December earthquake underscores that the time to act is now,” she says. “The question facing Vanuatu now is not just how to restore connectivity but how to build a resilient and equitable system that can weather future challenges.

“Will Australia, as a trusted partner, take this opportunity to act without the need for an external threat to spur it into action?”