It has only been a month since US President Joe Biden ended his re-election bid. At the time, few believed Vice-President Kamala Harris would win the Democratic nomination unopposed, and even fewer predicted she would be leading former president Donald Trump by nearly 3 percentage points nationally by the time the Democratic National Convention got under way.

In prediction markets, where punters bet on the outcomes of particular events, the odds of a Harris victory in the election on November 5 currently stand at 54 per cent, up from 10 per cent a week before Biden bowed out, according to spread betting site PredictIt. Trump’s chances, meanwhile, stand at 49 per cent, down from 69 per cent on July 15, two days after he narrowly survived an assassination attempt.

Harris has turned the tables on Trump, fired up the Democratic base and given her party a real shot at retaining the presidency. Yet her rapid ascent in the polls is mostly attributable to the energy and enthusiasm her candidacy has injected into the previously faltering Democratic campaign.

The fact remains that Harris is the second-in-command of an administration presiding over a country that more than 60 per cent of voters believe is on the wrong track, according to an average of polls curated by Real Clear Politics. Even though the resilient United States economy is the envy of the world, the pandemic-induced inflation shock – in particular the surge in food and energy prices – remains a political liability for the Democrats.

The findings of the latest ABC News/Washington Post/Ipsos poll on August 18 showed respondents trusting Trump more on the economy and inflation, the most important issues along with immigration. This poses an acute challenge for Harris, whose progressive economic agenda builds on “Bidenomics”. It also espouses policies championed by the left wing of the Democratic Party, making it easier for the Trump campaign to paint Harris as a socialist.

While some of her policies on tackling the cost-of-living crisis are sensible, such as measures to increase the supply of housing, others are brazenly populist and misguided. The one that has drawn the sharpest criticism is a pledge to go after companies engaging in “price gouging”, especially in supermarkets, by imposing the first federal ban on corporate price gouging.

Punishing firms for raising prices in response to imbalances in supply and demand is reminiscent of the price controls introduced by president Richard Nixon in the 1970s that ended up fanning inflationary pressures. Moreover, the focus on corporate greed reinforces the view that Harris is beholden to the left flank of her party. In an editorial on August 16, even The Washington Post accused Harris of resorting to “populist gimmicks”.

The vice-president has also proposed various tax credits and spending amendments that would add a further US$1.7 trillion to the already-bloated US budget deficit during the next decade, according to estimates from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

As if the Democrats’ fiscal irresponsibility was not bad enough, the party is almost as protectionist as the Republicans. Harris is likely to maintain the tariffs on Chinese imports imposed by the Trump and Biden administrations, mainly because it suits her political and economic agenda. Harris’s team gets “the same failing grade as Trump on tax and trade”, Adam Posen, head of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said in an interview with Foreign Policy earlier this month.

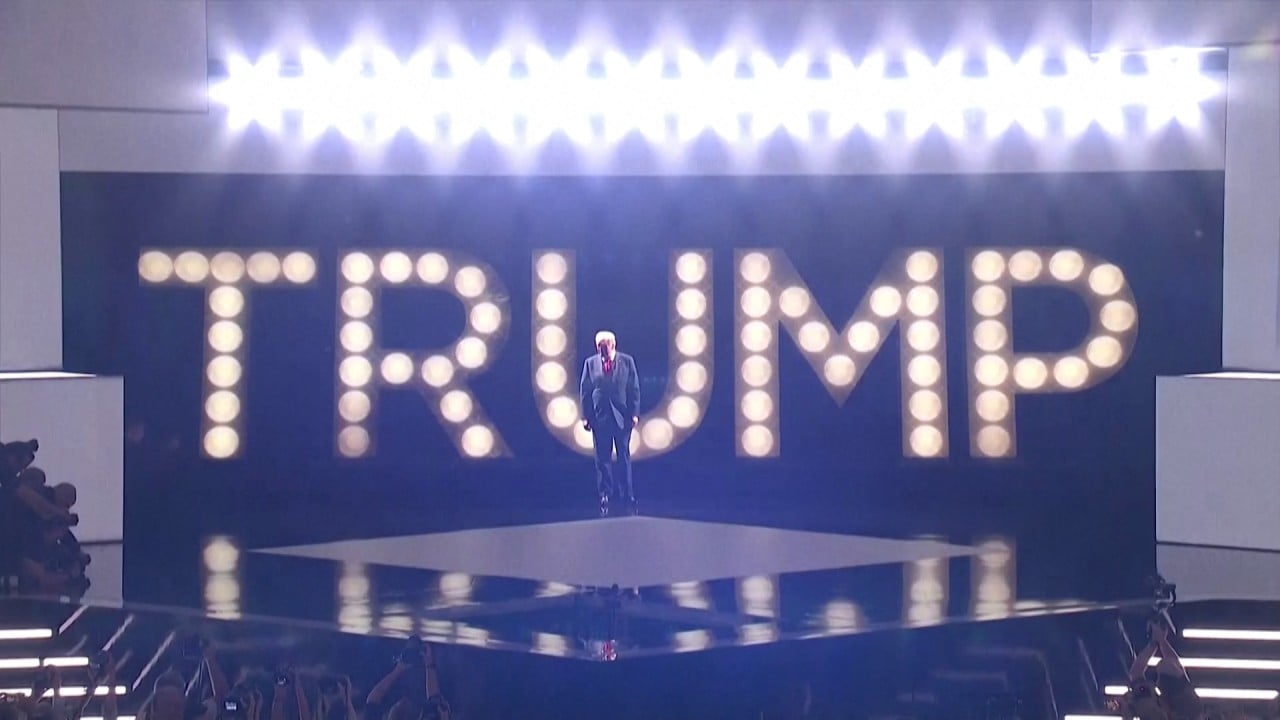

Concerns about Harris’s economic plans feed a narrative on Wall Street that a second Trump presidency would be better for business and asset prices, in part because of Trump’s regulation-slashing and tax-cutting agenda. The dramatic events in the presidential campaign during the past several weeks also add to the uncertainty and unpredictability of the election, making it more difficult for investors to assess and price political and geopolitical risks.

This is why contrarian and non-consensus views are proliferating. One of the most heretical ones is BCA Research’s prediction that Trump will offer China a “grand bargain” to help defuse trade tensions if he wins the election.

In a report on August 15, BCA Research’s chief strategist Marko Papic said investors should prepare for a “Nixon in China” moment, with Trump offering Beijing inducements to shift its electric vehicle production in Mexico to the US. This would “separate national security concerns from trade”, Papic said, adding that “if anyone can deal with China, it is Donald Trump”.

Not so fast. While a Republican president might be better placed politically to strike a deal with China, Trump himself cannot be trusted to do anything that is in the interest of anyone other than himself, least of all his country.

The economic risks posed by a Harris presidency pale in comparison with the colossal damage a second Trump term would inflict on the US and the rest of the world. The rule of law cannot be divorced from the economy and markets, no matter how inclined many investors are to play down the threat of a Trump victory or simply ignore the election altogether.

Harris might be toying with harmful price controls and underestimating the gravity of America’s fiscal problems, but she would not undermine US democracy, clip the wings of the Federal Reserve and sow chaos in the country and abroad. Just because Kamalanomics is not the answer should not distract, nor detract, from the huge menace of a second Trump administration.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory