A recent order by India’s Supreme Court has opened up the politically-charged issue of caste-based reservations for education and jobs, likely paving the way for a long-standing demand by the political opposition for a caste-based census of the world’s most populous country.

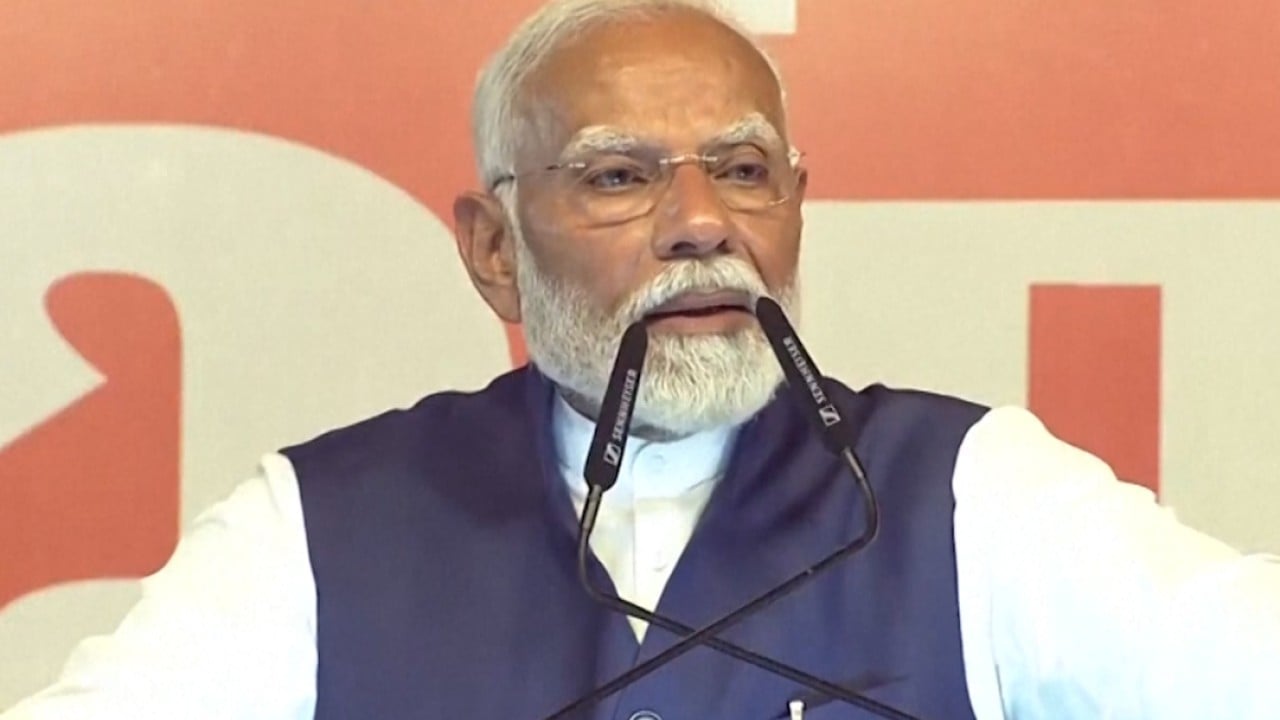

While the ruling could help the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) strengthen ties with less privileged groups, analysts say it also risks “setting off intra-Hindu sub-community rivalries”, creating divisions within the party’s base of support. It could also pressure Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government, as its stability now depends on coalition partners advocating for a caste-based census.

India’s Supreme Court ruled on Thursday that subclassification within Scheduled Castes is allowed for the purpose of granting reservations to improve equality, overturning a 2004 judgment that had asserted that Scheduled Castes were a homogenous group.

Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are those considered to be the most socio-economically disadvantaged in India and are officially defined in India’s Constitution to aid equality initiatives. Historically, lower castes have been denied equal opportunity to jobs and education because they were seen as socially inferior.

The latest court ruling said that Scheduled Castes are not a homogenous entity and there are distinct groups within the broader categorisation whose social and economic strata vary, which requires tailored action for different groups by state authorities.

“The court order is going to be of concern to every party. The [ruling] Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was trying to reach the less privileged among the Scheduled Castes, but the identification has to be done, which calls for more data and definitely a caste-based census,” independent political commentator Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay said.

“We don’t have clear data on the number of various sub-castes in various states. It opens a Pandora’s box because on what basis can we say this sub-caste is more empowered than the other,” he said, adding that each state government will need to determine the numbers to decide the proportion of reservations for such groups.

India last conducted a general census in 2011. It had planned to conduct the next one in 2021 before it was postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

India’s constitution requires government jobs and state-run educational institutions to reserve up to half of their placements for scheduled communities, whose development has long suffered at the hands of elite castes.

At present, 22.5 per cent of jobs and admissions to educational institutions in India are reserved for scheduled castes – a group that includes those previously referred to as untouchables but now collectively known as Dalit that forms the lowest socio-economic rung of Indian society – while around 27.5 per cent are reserved for other historically marginalised communities that the government classifies as “Other Backward Classes”.

Harsh Ramaswamy, an independent political commentator, welcomed the court ruling, saying it will open up reservations for politically under-represented sections of lower castes.

“Policies have to reach people equally. Many people were left out [of reservations] because they were not politically influential. This will bring true social justice,” he said, adding that a caste-based census is a logical next step to determine various categories in a country as diverse as India.

Opposition parties say a new caste census is needed because marginalised communities such as those classified as “Other Backward Classes” now account for over half of India’s population and should therefore have more jobs and spots in education institutions reserved for them.

In the run-up to the national election that ended in the first week of June, India’s main opposition leader, Rahul Gandhi from the Congress party, demanded caste surveys in states under his party’s control.

In May, Gandhi said his party would remove a Supreme Court-mandated 50 per cent cap on caste-based reservation and increase quota benefits for people from backward and tribal communities, but he has yet to make any public statement since Thursday’s ruling.

Regional political leader Mayawati – a former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh state and leader of the Bahujan Samaj Party that advocates for social change for backward castes – has also been calling for the removal of the 50 per cent cap on reservations.

Risks abound

Analysts said the latest Supreme Court order could enable the BJP to make a stronger connection with less privileged communities but risks splintering its traditional base of the country’s majority Hindus by deepening fractious caste lines.

“A basic fear of the BJP is going to be about setting off intra-Hindu sub-community rivalries. It could break pan-Hindu solidarity,” Mukhopadhyay said.

Modi’s government may be forced to implement such a caste-based census because his government’s stability is dependent on coalition partner Nitish Kumar’s Janata Dal (United) party, which has been at the forefront in demanding a caste-based census.

There is precedent in India for a seemingly innocuous spark arising from the caste issue to catalyse into political upheaval. Former prime minister VP Singh’s government was ultimately brought down in 1990 by fierce opposition to his plans to reserve more government jobs for members of lower castes.

Colin Gonsalves, a senior lawyer and founder of the Indian non-profit Human Rights Law Network, said the court judgment appears to have some oversight.

The judgment may have gone overboard in suggesting that certain “creamy layers”, or those who are well off economically within the Scheduled Castes, may be overlooked in terms of reservations.

The basis for reservations is social discrimination, such as lower castes not being allowed to share the same table as an upper caste, rather than on economic criteria alone, Gonsalves said.

The other aspect for consideration is that lower caste quotas in elite government positions are often not filled because powerful upper castes indirectly assert their influence in the selection of candidates for these jobs, he said.

“The administration is in the hands of the upper castes. There is going to be huge controversy in the country because of the two mistakes made in the main judgment,” Gonsalves said.

“The right thing to do was to ensure full reservations and then take up other reforms,” he added, referring to the observations about excluding “creamy layers”.

Analysts say authorities would need to quickly begin work on gathering data and setting the criteria for reservations for different sub-castes because the exercise will take time.

Ramaswamy said the central government will have to make a broad statement based on the court judgment and then different states will need to figure out the sub-castes which could vary from region to region. India has 28 states and eight federally-administered territories.

“The central government will only make a clear statement and states will have to pick up from that and make their own policies,” he said.