While the recent Nato summit celebrated the organisation’s 75th anniversary, its focus on China underscored a shift in geopolitical dynamics. The transatlantic alliance, which was founded to defend against the threat from the Soviet Union and later Russia, is increasingly critical of China and its global role.

Nato has voiced deep concern over China’s failure to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and accused Beijing of providing material and political support for Moscow’s war efforts. This marks a significant turn, with Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg calling it the alliance’s strongest message to date on China’s involvement in the conflict.

The intense focus on China comes at the same time as a growing feeling of unease within Nato. Some Western strategists had anticipated that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could end up akin to the Soviet quagmire in Afghanistan, potentially leading to the downfall of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Yet, despite funnelling large amounts of financial support and military equipment to Ukraine and imposing severe financial restrictions on Russia – including freezing large parts of its foreign reserves – the conflict in Ukraine has continued into a third year.

Russia has spent heavily on defence during the conflict, allocating upwards of 6 per cent of its GDP to military spending since its invasion began in February 2022. This is in contrast to Nato member countries, whose defence spending as a percentage of GDP tends to be lower.

Moscow has also shown economic resilience thanks to its considerable financial resources, including US$580 billion in foreign currency and gold reserves. This economic cushion supports its military efforts and allows for sustained investment in its defence industries.

Meanwhile, the defence industries in many Nato countries, particularly in Europe, have largely been scaled back following the end of the Cold War. War games and assessments have indicated potential shortfalls in ammunition production and military readiness among alliance members, highlighting a gap in industrial capacity and preparedness for high-intensity conflicts.

While European allies remain wary of China, many are also concerned about being caught in the crossfire of escalating Sino-American tensions in addition to the effects of Russia’s war in Ukraine. They still consider Russia as the main threat to Nato and are sceptical about suggestions of expanding the alliance’s role into the Indo-Pacific.

This scepticism towards Nato’s approach is exemplified by Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, who is far friendlier towards China and Russia than many of his counterparts in western Europe. Just a few days before the Nato summit, Orban visited Putin and President Xi Jinping. Orban has moved to increase Hungary’s engagement with China, resulting in €16 billion (US$17.4 billion) of investment by Chinese firms, making China the top investor in Hungary.

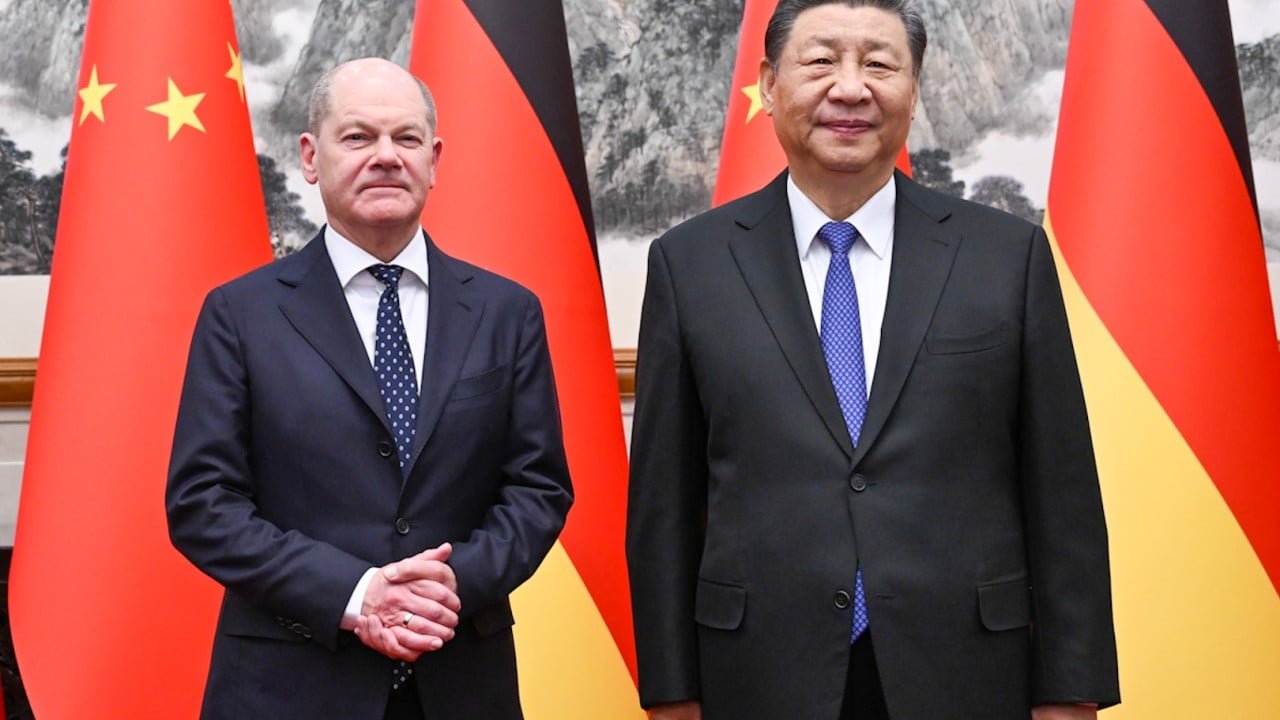

European nations who rely on commerce with China want to avoid anything that would increase tensions with an important trade partner. Consider Germany, the economic engine of the European Union. In April, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz visited China and discussed how to consolidate and develop their relations. As the second- and third-largest economies globally, their strategic partnership not only enhances bilateral ties but also influences the Eurasian continent and global stability.

Germany is feeling the effects of the deterioration of economic ties with Russia. No longer having access to cheap natural gas from Russia has resulted in a prolonged energy crisis and an economic downturn reminiscent of the 2008 financial crisis, according to a report from two former economic advisers to the German government.

While many commentators are likely to focus on the anti-Chinese rhetoric that dominated the Nato summit, far fewer will recognise that the greatest threat to the transatlantic alliance is coming from within. The unsuccessful assassination attempt on former US president Donald Trump appears to have been a significant boost to his hopes of returning to the White House in November’s election.

Trump was one of the alliance’s loudest and most vociferous critics during his tenure. If he does return to office, it seems likely he will demand reversals of several current positions currently held by the US government, including its generous support for Ukraine’s war effort.

Media reports suggest Trump will pressure Ukraine to give up some of its territory in a peace plan that will include the easing, and perhaps full suspension, of sanctions against Russia. He is also likely to step up his criticism of Nato and member countries who do not increase their military spending.

This is why Nato leaders are making moves behind closed doors to “Trump-proof” the alliance, putting in place contingency plans to keep the group together through a second Trump term. Their options include streamlining procurement of critical military equipment for Kyiv.

Even with a head start in planning, Nato faces an uncertain future. In a piece last month titled “Could Nato survive a second Trump administration?”, Brookings Institute senior fellow Steven Pifer wrote that the alliance would not survive in its current form if Trump is re-elected, “at least not with the United States as a committed ally and alliance leader”.

As Nato moves on from its 75th anniversary celebrations, it confronts profound challenges both from without and within. The intensified focus on China risks taking attention away from internal rifts and the prospect of Trump altering the course of the alliance’s future. The path ahead remains fraught with uncertainty as Nato’s leaders fortify against these threats.

Dr Tarek Cherkaoui is manager of TRT World Research Centre based in Istanbul, Turkey