Belarus, one of Russia’s few allies in Europe, seeks to strengthen its economic, political and military ties with China. Isolated from the West and heavily dependent on Beijing, Moscow is in no position to prevent a potential Chinese encroachment into the Kremlin’s zone of influence. But does China really have significant geopolitical ambitions in Belarus?

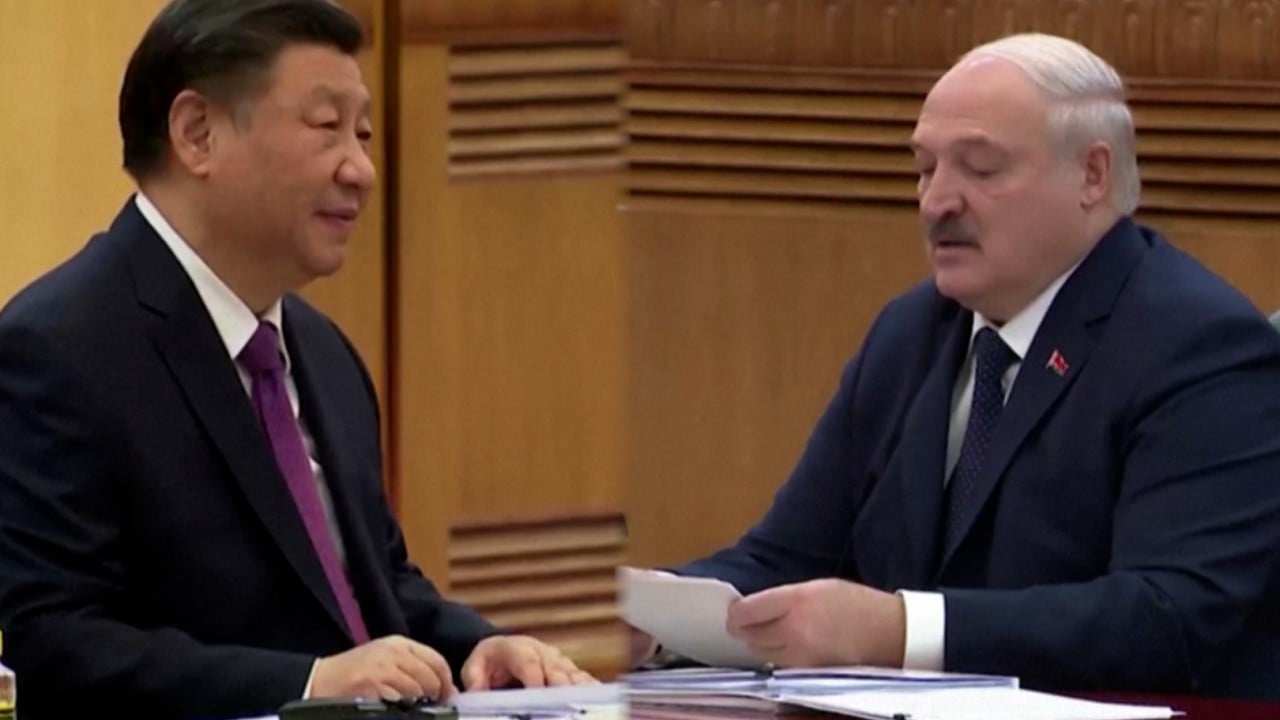

In 2016, while Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko still had relatively good relations with the West, Minsk and Beijing established a comprehensive strategic partnership. In 2017, the Belarusian government offered 22 state-owned enterprises for privatisation exclusively to Chinese businesses, but none have attracted any interest.

That year, the volume of Chinese investment in Belarus was comparatively small. However, by 2019, China was among top three international lenders for Belarus, although Beijing’s economic presence in the former Soviet republic remained relatively low.

A lack of structural reforms, as well as a Soviet-style economy, seemed to prevent greater influx of Chinese investment. However, that has not discouraged Lukashenko from seeking to strengthen economic relations with Beijing. Following the controversial presidential election in 2020, Lukashenko turned to China for loans, investment, and military and political support.

As a result of Premier Li Qiang’s recent visit to Belarus, Beijing and Minsk agreed to expand security and economic relations. According to Li, Beijing stands ready to work with Belarus to “push for the high-level development of their all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership to better benefit the two peoples”.

The Chinese and Belarusian leaders also expressed support for “peaceful resolution of conflicts and constructive bilateral dialogue between countries”. Such rhetoric suggests they have the same approach regarding Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Belarus is nominally Russia’s ally in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), and it indirectly participated in the Russian invasion of Ukraine by allowing Moscow to use Belarusian territory to attack northern Ukrainian regions of Kyiv and Chernihiv in 2022. However, Lukashenko seems to have changed his stance slightly on Russia’s actions in Ukraine over the past two years.

After Ukraine launched its cross-border offensive into the Kursk region, Belarus did not take any measures to help its CSTO ally. This was despite Article 4 of the treaty stating that an act of aggression against one member state will be considered a collective act of aggression on all member states. Instead, Lukashenko urged Moscow and Kyiv to negotiate an end to their conflict, pointing out that “neither the Ukrainian people, nor the Russians, nor the Belarusians need it”.

Last year, Lukashenko supported the Chinese peace plan for Ukraine – a document stating that “dialogue and negotiation are the only viable solution to the Ukraine crisis”. His most recent peace-promoting rhetoric indicates that he still holds the same position on Ukraine as Beijing. But Belarus’ proximity to Russia and its economic dependence on its giant neighbour are crucial reasons Lukashenko cannot fully adopt China’s strategy of “pro-Russian neutrality”.

While Minsk continues to rely heavily on Moscow for political and financial support, it also seeks to balance this dependence by forging closer ties with Beijing. Belarus joined the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) last month, while on July 8 the two nations conducted joint military exercises at the Brestskiy training range next to the border with Ukraine and Poland. This has led to growing fears about Beijing’s reported plans to build a military base in Belarus.

Being a landlocked nation far from China, it is questionable how appealing Belarus would be to Chinese military strategists. However, as part of the military cooperation between the two countries, Chinese and Belarusian companies have jointly developed the Polonez multiple launch rocket system. The last thing the West wants is this weapon ending up in Russian hands.

But since the Polonez uses Chinese-made missiles, its potential transfer from Belarus to Russia would require Chinese consent. So far, Beijing and Minsk have been careful not to cross the West’s red lines in their military cooperation, both with each other and with Russia. That is why their ties will largely remain within the economic sphere for the foreseeable future.

From the Chinese perspective, Belarus is not only an important partner but a crucial hub for its Belt and Road Initiative, as well as for freight trains between China and Europe. Therefore, it is no surprise that the two countries agreed to strengthen cooperation on China-Europe freight trains by promoting infrastructure connectivity and jointly ensuring the safety of the China-Europe train transport corridor.

For Belarus, on the other hand, China and Russia are key markets for its export-oriented economy. As one of Belarus’ largest trading partners, China has so far financed at least 35 joint projects in the former Soviet republic. But Lukashenko now wants to see more Chinese technology in Belarus even though his country remains firmly in Russia’s geopolitical orbit.

The Belarusian leader probably believes he can maintain strong relationships with both China and Russia without having to reduce cooperation with either. This is underscored by Belarus’s decision to join the SCO, which reflects Minsk’s intention to strengthen ties with China while continuing to nurture its partnership and military alliance with the Kremlin.

In other words, Lukashenko looks as if he’s trying to revive his “multi-vector” foreign policy, a concept he had to abandon in 2020 after Moscow effectively helped him stay in power following mass protests that threatened his rule. This time, he may well view China as a counterbalance to Minsk’s strong dependence on Russia.

Nikola Mikovic is a freelance journalist, researcher and analyst based in Serbia