Researchers in Hong Kong have unearthed what they have said are rare traces of an old shrine from the 1940s during the city’s Japanese occupation, but authorities have described the discovery as “conjecture” that requires “verification”.

Historians argued the purported site, located in the popular Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, was significant because few artefacts had survived from that period in the city’s history and it could give a glimpse into the Japanese rule that lasted three years and eight months.

“The occupation was not very long. It’s only normal that there are not many remnants from the three years or so,” said Stanley Lee Chak-yan, chairman of the Hong Kong History Study Circle.

The organisation, which was founded by history enthusiasts in 2004, helped to discover boundary stones for a colonial-era settlement in 2021. The circle regularly hosts activities and publishes content to promote the city’s heritage.

According to Lee, remnants made of stone that resembled the layout of a typical Japanese shrine have been hiding in plain sight for decades within the verdant gardens in Mid-Levels.

He said the features included a long passageway – or sandō in Japanese – which was flanked by two stone bases likely to be put in place to hold a pair of lion-dog sculptures, also known as komainu, the Japanese guardians of shrines.

An area towards the end of the passageway, in what is now a rain shelter, was believed to be the site of a haiden – or oratory – where ceremonies such as weddings would take place, he explained.

Behind it were steps leading up to a raised platform that would have been the honden – or main hall – which housed one or more deities known as kami and would have been the site of religious activities.

“The local sources we have from the time are newspapers. There aren’t really any records from the British colonial government because this was during the Japanese rule,” Lee said.

“The [British] might not have realised it was a shrine. Instead, they might only consider it an alteration to the gardens by the Japanese,” he said.

Despite text records of a shrine being built in the gardens at the time, its exact location within the gardens was not known and subsequently became a forgotten part of history.

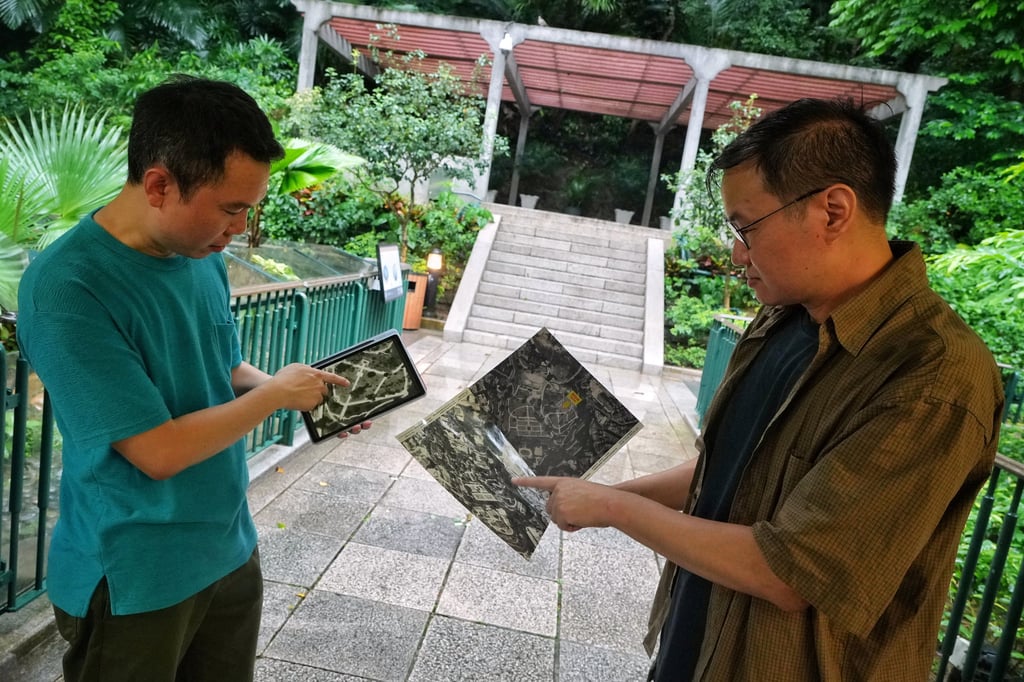

Lee and his colleague Gleion Shing Lik-fung relied on aerial photographs of the gardens before and after the Japanese rule from the Lands Department and one sourced from the US by Baptist University’s Dr Kwong Chi-man to help identify the traces of the shrine.

The photograph before the occupation showed meandering paths in the gardens that were founded by the British in 1871, after the occupation, it was straightened into the stone-paved passageway that resembled the layout of a shrine.

“Other [Japanese-colonised] places at the time also had shrines, including Singapore and Taiwan. So it made sense that Hong Kong would have one, too,” Shing said. “It probably only came to be a shrine just before they surrendered, or it was in its earlier phases of construction.”

The pair said the whole shrine would have extended up to the site of Canossa Hospital on Old Peak Road if it had been completed in full.

“There should be a high chance that these will be kept here given it’s government property. As for grading it [as a monument], I hope it will be possible once more information is found, such as whether the stonework is really from 1944,” Lee said.

“We are making educated hypotheses, and there aren’t concrete official records. We hope that if more people know about this, there will be a higher chance of securing more information.”

Baptist University historian Kwong said Hongkongers only had a “faded memory” of the period as many who lived through the occupation had died, leading to “a host of unverified myths” taking hold.

“Such myths include conjectural locations of mass graves and massacres. So when we have concrete traces or remnants of that part of history, they become tangible hints that allow us a glimpse of the past,” he said.

According to Kwong, such sites serve as important proof that the Japanese had plans for large-scale public works despite their short occupation, which also included a substantial extension of Kai Tak Airport, as well as the expansion of Prince Edward Road East and Clear Water Bay Road towards Kowloon Bay.

He considered the latest discovery rare, as it could be the largest religious site among just a handful left behind by the Japanese, as those in Leighton Hill and Hung Hom no longer existed.

In a reply to the Post, the Antiquities and Monuments Office described the discovery of the structures as “conjecture” that was “subject to verification”.

“[The office] has recently conducted a site visit to the gardens but has not identified items of particular interest from the built heritage perspective,” the statement said.

It also said that whether the structures would be graded as historical monuments in the future depended on the availability of new and reliable information to show their heritage value.