In the first of a two-part series, Aileen Chuang looks at what Hong Kong’s financial regulators, banks and social media network operators must do to stamp out scams.

One Sunday afternoon in June, May Lee* received eight phone calls from people who claimed to be the customer support staff from WeChat, the ubiquitous Chinese super app that provides everything from social networking to e-payments and investments.

Lee’s credit cards and bank account had been frozen, the callers falsely asserted, because she had provided inaccurate data when she tried to unsubscribe an insurance policy on WeChat’s wealth management platform. To free her account, she had to raise her daily remittance limit to HK$1 million (US$128,000) and make a handful of transfers to verify her identity, the callers said.

To prove their bona fides, the callers attached numerous photographs and documents: certifications by China’s securities watchdog, the coverage contract of one of China’s largest state-owned insurers PICC, as well as chat records with bank staff and with a chatbot operated by UnionPay, the payments network.

They were all fake. The entire scheme was an elaborate ploy to trick Lee into transferring money to a confidence trickster. After phone calls that totalled four hours, Lee found herself poorer by HK$570,000.

Lee was the victim of a phone scam. In Britain, this type Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud will compel the bank involved to compensate her when a law comes into effect on October 7.

Not in Hong Kong. Lee, an office worker in her early 30s, has no recourse to recover her money because she had authorised her push payment, albeit into a scammer’s account.

“I was so surprised that my bank did not send a single alert to me,” Lee told the Post, declining to name the bank. She sent an “angry email” to her bank, but to no avail, she said. No one has been arrested for the crime.

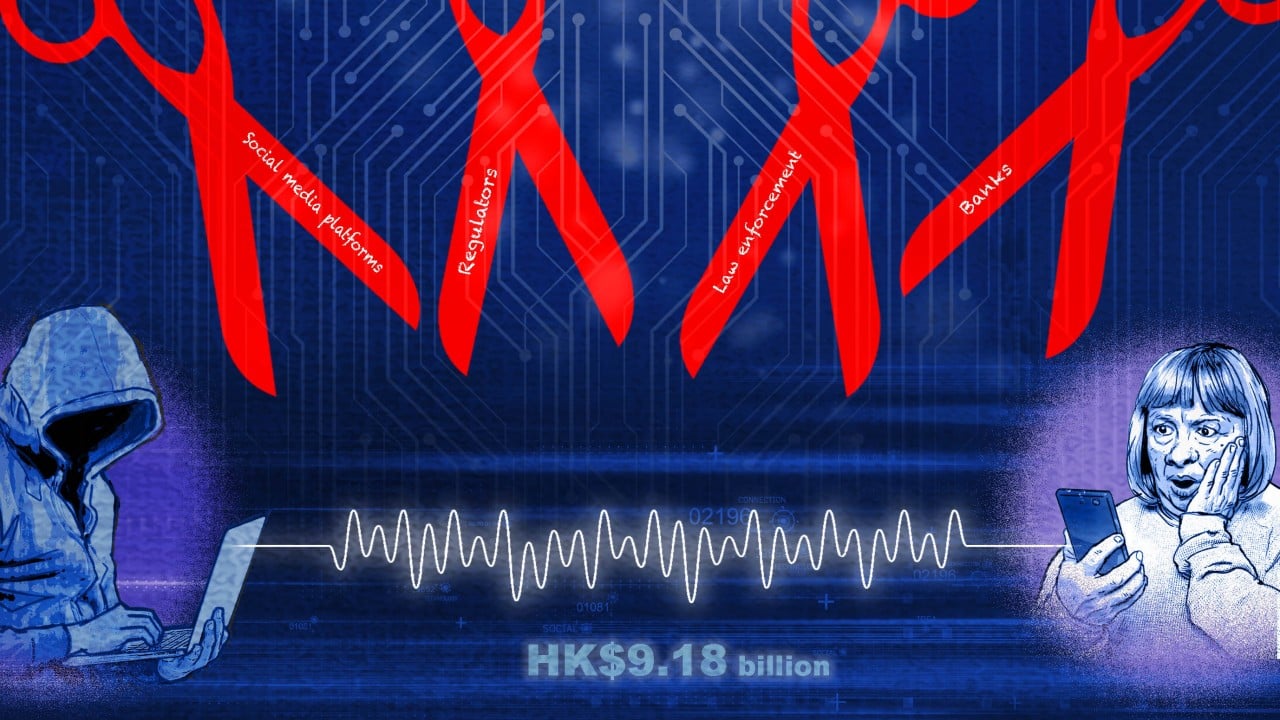

Lee’s case was hardly unique. Scams nearly doubled in value last year in Hong Kong to HK$9.18 billion, while the number of cases jumped 42.6 per cent to 39,824, putting the city of 7.5 million people at the top of the world in per-capita losses from fraud. Investment scams accounted for HK$5.9 billion of those losses.

APP-related complaints jumped 16 per cent in the first six months, said the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), while financial losses from cybercrime cases rose 31 per cent to HK$2.66 billion, according to police data.

Lee’s frustration, juxtaposed with the seemingly easy windfall from fraud, showed how Hong Kong’s banking and financial regulations have failed to keep up with the schemes and ploys of fraudsters. Commercial banks are hamstrung, as they must tread a fine balance between privacy and convenience for their customers, and being overprotective when it comes to clients’ remittances.

HKMA, which oversees the 149 licensed banks in the city, has rolled out a suite of applications and measures to protect the public from online deception. However, these amount to piecemeal measures in a regulatory vacuum, where banks and social media networks are not legally required to weed out fraud, while a cybercrime law remains a work in progress.

“Hong Kong is lagging in enacting laws to fight scams,” said Johnny Ng Kit-chong, a lawmaker in Hong Kong’s legislature and the founder of an anti-deception alliance.

Will a cybercrime law in Hong Kong help to stem the rot if banks and social media platforms are made to proactively crack down on suspicious behaviour?

Other jurisdictions show how it is done. Australia’s government proposed in November 2023 a code that makes it mandatory for banks, digital communications platforms and telecoms providers to assume their anti-scam responsibilities. The code, expected to be introduced by the end of this year, may contain sector-specific codes and standards, with penalties for non-compliance.

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) plans to implement a “shared responsibility” framework later this year, where losses from phishing scams are borne by the banks and the telecoms network. Banks, as the custodians of their customers’ money, bear the first line of responsibility and are accountable for any losses due to dereliction of duty under that framework, MAS said.

Protection has also been strengthened in Britain. Starting on October 7, banks must reimburse APP fraud victims within five working days, with the value of the fraud shared by the receiving and sending banks.

“The UK financial services regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority, has made this a priority and recently conducted a review of how banks mitigate the risks of APP fraud and [scams] more broadly,” said Jonathan Cary, a London-based partner at RPC.

Closer to Hong Kong on the mainland, an Anti-Telecom and Online Fraud law has been in place since 2022. It requires banks to assume the liability for risk prevention and control. Under certain circumstances, banks may be fined or ordered to cease operations if they violate the law.

Still, stopping suspicious payments may be challenging because banks “provide the platform with the necessary terms and agreements,” said Chad Olsen, head of forensic for Hong Kong at KPMG China.

“Their obligation is to report any suspicious transactions,” not to proactively stop them, he said.

Lilian Sin, the Hong Kong head of financial crime compliance services at KPMG China agreed. Catching “transactions associated with scams at the exact moment they take place can be quite challenging,” she said.

Information sharing could address the challenge. The HKMA plans to amend Hong Kong’s laws to allow authorised banks to share information on individual accounts suspected of involvement in financial crimes, said Raymond Chan, HKMA’s executive director for enforcements and anti-money-laundering (AML).

Currently, only information on suspicious corporate accounts can be shared under a platform called the Financial Intelligence Evaluation Sharing Tool because of privacy concerns.

HKMA will also widen the scope of alerts beyond its Faster Payment System to include internet banking and transactions at bank branches, based on the police database called Scameter, in which suspicious web addresses, emails, platform usernames, bank accounts, mobile phone numbers and IP addresses are recorded. Starting Sunday, 32 banks and 10 operators of stored-value cards will send warnings when users transfer funds to suspicious accounts.

These efforts have to be “adequately resourced and coordinated” with “senior management oversight” to deliver more robust customer protection, HKMA said in a letter to the banks’ CEOs last October.

“The aim is to empower customers by giving them information and letting them decide whether they want to proceed with a transaction,” Chan said in an interview with the Post.

Banks resort to AI to fight fraud

“We made significant strides in bolstering our intelligent anti-fraud platform, such as developing an artificial intelligence (AI) model to strengthen our detection capabilities,” said Eric Liu, the general manager of personal banking risk at Bank of China (Hong Kong), one of the city’s three currency-issuing banks. The AI system helped the bank raise the number of intercepts fourfold.

HSBC, the largest lender in Europe and Hong Kong, developed an AI system with Google to check for financial crime worldwide. It has found two to four times more financial crimes than before, with 60 per cent fewer false positive cases through ratification by calls to customers.

Last year, HSBC increased its anti-scam IT investment involving “advanced analytics and fraud prevention capabilities upgrades” by 70 per cent in Hong Kong, compared to 2022, a spokesperson said.

“The HKMA does not expect every fraudulent transaction to be blocked. What it expects is systems and controls to be designed and implemented for the risks faced by the bank, and checked and tweaked on a regular basis, including internal audits to determine whether they are working properly,” said Jonathan Crompton, a partner at law firm RPC.

To be sure, anti-scam laws should not go to extreme because the individual is still at ground zero in the fight against fraud. Reimbursing every loss may make the public inured to outrageous schemes, rendering them easier victims. Financial efficiency may also be severely damaged if every transaction is scrutinised, experts said.

“If we enact a law as tight as the anti-money-laundering Ordinance, the business environment in the city will become difficult,” said Ng the lawmaker.

There may be a way out. Fraud could become a subset of the AML Ordinance because the proceeds of fraud typically are categorised as money laundering. Some bankers already hold themselves to this standard in handling fraud cases.

“The AML law in Hong Kong is already a powerful and useful legislation for banks for responding to fraud,” said Henry Yu, chief compliance officer at Airstar Bank. “Fraud is already an indictable offence in Hong Kong where banks can use the AML law to report suspicious transactions and stop the proceeds of the indictable offence.”

Another option is to improve the legal infrastructure to enable fraud victims to recover their losses quickly at lower costs through civil suits, he said.

Fraud must be fought at its source on social media

Should banks bear the sole responsibility in a fraud case? Social media platforms – from Meta’s Facebook to Tencent’s WeChat to Elon Musk’s X – are typically the entry points to the elaborate schemes where deception takes place, said Josh Plant, an AlixPartners’ director.

“It’s at the point [where] the victim makes the payment, [that allows] the case to enter the banks,” he said, adding that social media platforms should bear some responsibility for the scams.

The Hong Kong Association of Banks (HKAB), the influential guild of the city’s lenders, agreed. “Greater cross-sector cooperation is necessary to tackle the problem at its source,” since most online fraud cases originate on tech platforms, HKAB said.

Any legislation in Hong Kong to arrest deception schemes must also include social media platforms, said Ng the lawmaker.

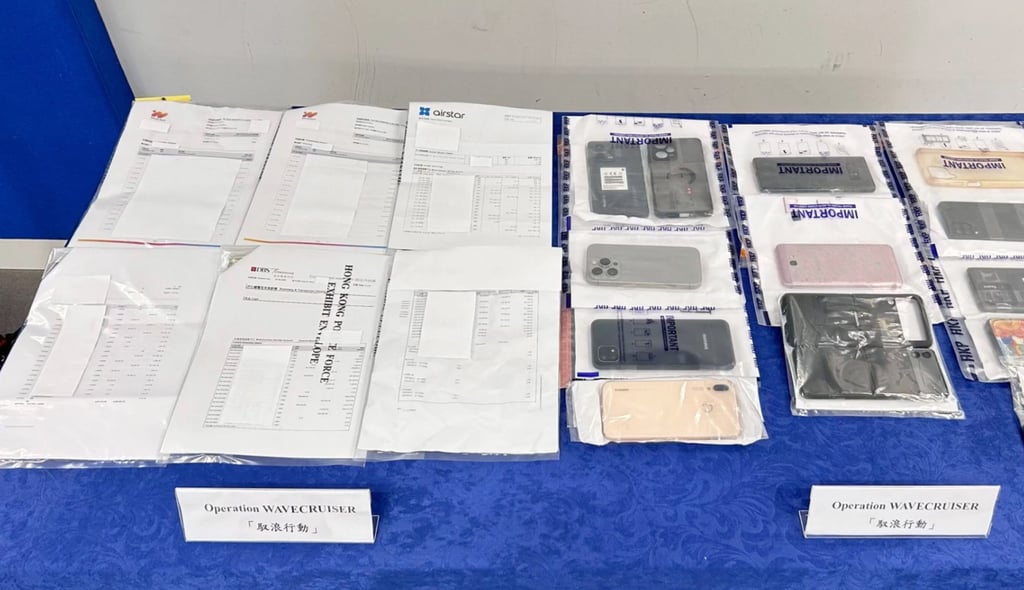

Action is already afoot. The Hong Kong Police Force asked Facebook to take down more than 5,200 fraud-related accounts in the first half of last year, 95 per cent of which were successfully removed. “Police and the relevant stakeholders have been cooperating smoothly in this regard,” the force said in a statement.

“More can be done via partnerships between the public and private sectors, information sharing, public education and investments in technology,” said Debra Au, the head of legal, compliance and secretariat at DBS Hong Kong, who is also the co-chair of the Global Coalition to Fight Financial Crime Asia Chapter.

The city could do with an “anti-fraud tsar or evangelist,” said Olsen of KPMG China. “From a structural standpoint, we need a central owner to fight fraud.”

That may reside at the Two IFC building in Central, where the HKMA operates from an office on the 55th floor, with a view across Victoria Harbour. The de facto central bank’s deputy chief executive Arthur Yuen Kwok-hang acted in a musical skit with the Cantopop icon Wan Kwong to showcase common phishing tactics used by scammers.

“We will monitor legal and regulatory developments in other jurisdictions and assess whether there are any good practices suitable for the local circumstances,” said the monetary authority’s AML chief Chan.

*Name changed to protect the victim’s identity