It was April, and TikTok had no clue what was coming.

At some point along the endless scroll through the kinds of short videos one would expect to drive traffic on the social media platform – recipes, animals, political invective – users began to latch onto an unlikely sensation: a little-known Chinese company touting the virtues of an industrial-grade food additive.

Donghua Jinlong, a chemicals concern in the northern province of Hebei, had put out a one-minute video to promote glycine, its headline product. One of many Chinese firms looking to break into overseas markets, the company was taking an unusual approach to advertise the compound – an amino acid mostly used in pharmaceutical manufacturing and only occasionally as a dietary supplement.

But four months later, orders have more than tripled, causing a shortage due to the unexpected barrage of attention, administrative director Chen Liya said. “In April we had no idea,” Chen said. The results, they thought, were “strange and puzzling.”

The video has received more than 100 million views, and led to countless spin-offs and memes extolling – with, perhaps, a touch of irony – the product’s many wonders, according to an August 13 report by the Chinese radio and television producer Yi Shi Yi Se Cultural Communication.

This isn’t the first time a Chinese social media phenomenon has piqued interest from across the sea.

Content creator Li Ziqi, a Sichuan-based internet personality famous for her cinematic videos of farm life, holds the Guinness World Record for most YouTube subscribers on a Chinese-language channel.

Initially starting as an online agricultural shop, Li’s intricately produced shorts proved meteorically popular in the West, providing an escapist outlet for city dwellers and an idyllic glimpse into Chinese culture.

Donghua Jinlong’s management assumed influential TikTok users were crucial in spreading the video around the site, creating a multiplier effect through the platform’s algorithms that helped rocket the company to its present level of prominence, Chen said.

This case, though rare, shows how quickly even the most esoteric Chinese brand can catapult to fame overseas through a combination of sympathetic internet users, a willing market and a spark of luck, analysts said.

“I’m not surprised it happens,” said Liang Yan, an economist at Willamette University in the US state of Oregon. “Some of it is deliberate – companies get influencers to pass things on.”

Part of the formula relies on an experimental market such as youth in the US, said Albert Ma, who graduated last year with a political economy degree from UC Berkeley.

“Donghua Jinlong is a perfect target for Gen Z and Gen Alpha in the US, who may have no idea what industrial-grade glycine is, but are willing to mindlessly echo ‘Donghua Jinlong’ for laughs,” Ma said. “The most intriguing part is, this could have happened with any other obscure Chinese company.”

One video shows a man about to unbox what’s presumed to be glycine. Another shows someone composing song lyrics about the product, which is sometimes taken as a supplement to treat conditions like diabetes or insomnia – though research is limited on its efficacy in this regard.

Diana Regan is an influencer whose Donghua Jinlong parody videos garnered from 200,000 to 1.2 million views on Instagram.

“I loved the absurdity of a company whose target audience was other businesses accidentally going viral on TikTok,” Regan said. “The style was so honest and authentic, coming from an industrial manufacturing company posting to an app whose user base is primarily consumers.”

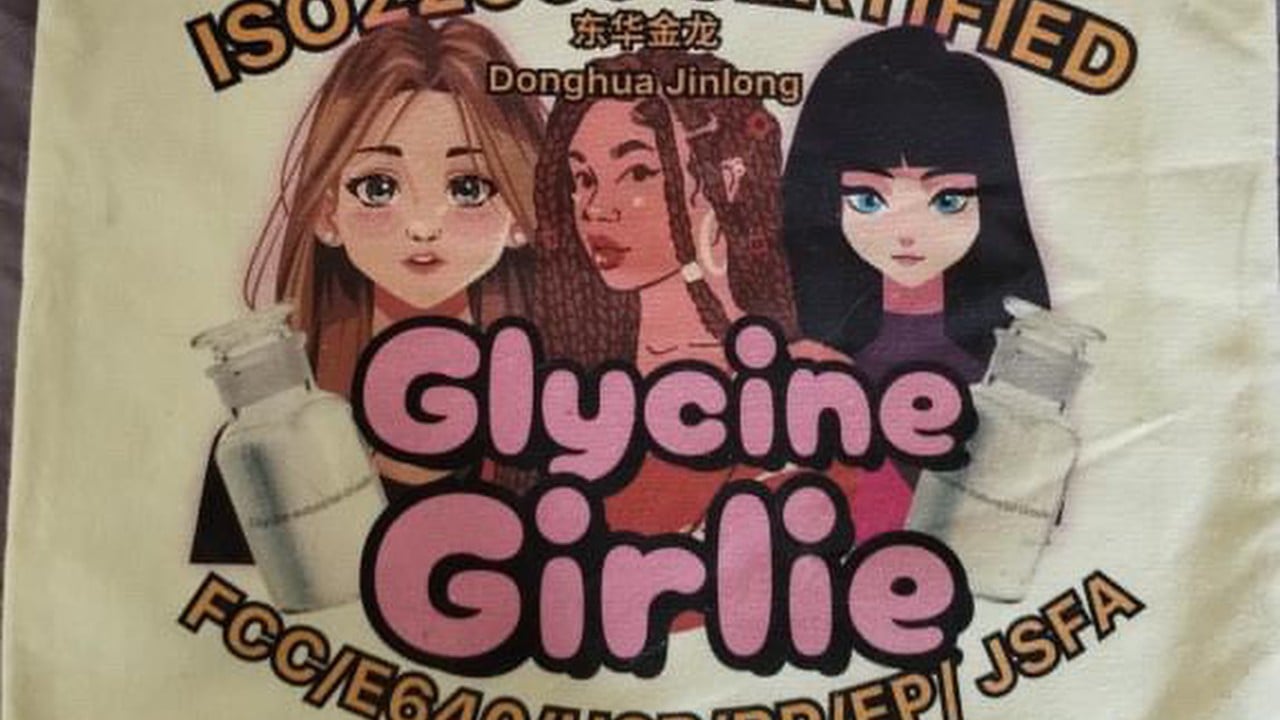

The glycine phenomenon prompted clothing manufacturers to capitalise on the trend with unofficial merchandise, with Donghua Jinlong itself eventually coming up with their own range of official apparel, featuring clip art Regan created on graphic design platform Canva.

Robb Marrocco, a TikTok user specialising in food and beverage content with 726,500 followers, got in on the craze with a video showing him making and drinking a cup of “espresso” with a purported infusion of Donghua Jinlong glycine.

“I love that it advertises an incredibly niche, industrial product to an audience that would never possibly need it and would never have otherwise known it existed,” he said.

But viral fame of this nature is rare and seldom lasts, said Lu Xiang, a research fellow at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Most sustainably successful Chinese companies use social media to push products that are backed by strong research and development, he said, pointing to consumer electronics brands Huawei and Xiaomi as examples.

In the meantime, executives at the 45-year-old company are riding the wave. The first hint that they had happened upon a phenomenon came when Chinese university students started visiting the campus to “check in” to the location online, Chen said, and the notoriety only grew from there.

Whether that new-found renown has resulted in higher sales for the glycine itself remains an open question. Chen would not disclose a dollar figure for orders received since April, citing tough competition in the domestic market.