China is pushing for peace on the Indian border as Beijing preps for a more intense U.S.–China competition under the new Trump presidency.

NEW DELHI—India and China agreed on a six-point consensus to guide bilateral relations on Dec. 18 as India’s national security adviser and China’s foreign minister met for the first time in five years.

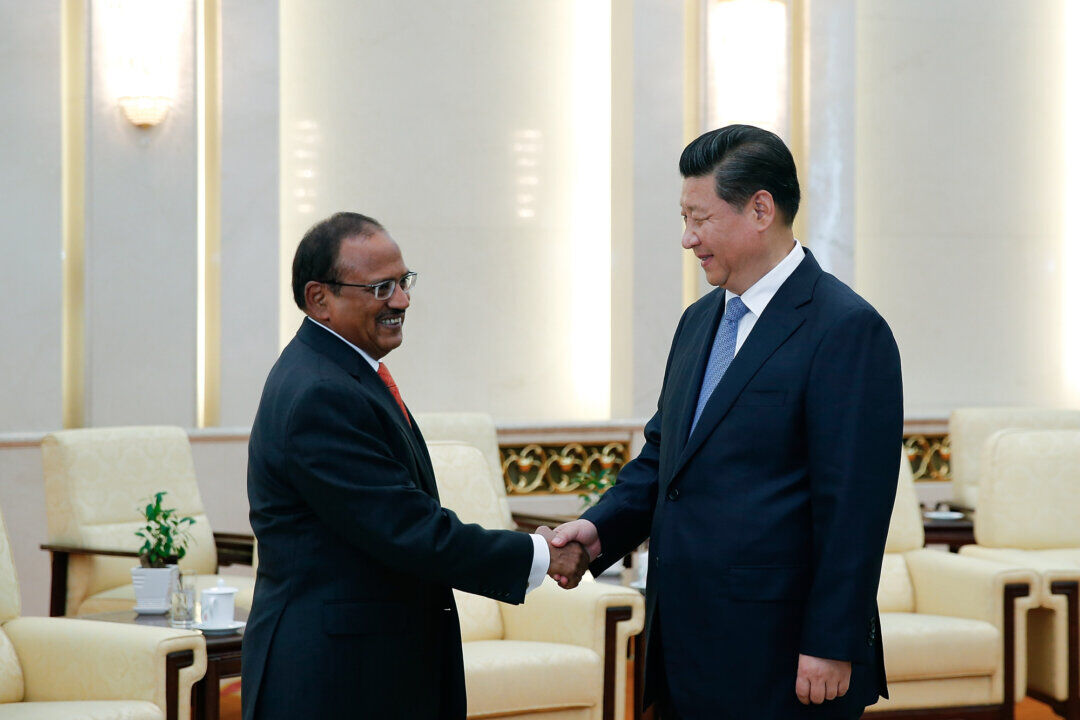

The talks in Beijing between India’s Ajit Doval and China’s Wang Yi were aimed at solving the two countries’ long-running border dispute.

Meanwhile, experts say the Chinese Community Party (CCP) has stepped back from its hegemonic behavior toward India. The softened stance is due to various geopolitical factors, they say, including President-elect Donald Trump’s second term, which is expected to intensify U.S.–China competition.

Beijing’s altered behavior may be an attempt “to recalibrate in a Trump’s world,” said Harsh Pant, vice president of studies and foreign policy at the New Delhi-based Observer Research Foundation.

It also “reflects the sense that things have terribly gone wrong with India and something needs to be done about it—to perhaps re-engage India in a way that allows the possibility of China being seen as a neighbor that can be trusted,” Pant told The Epoch Times.

Pant believes the meeting between Doval and Yi will not result in any dramatic changes in India’s posture, nor does he expect the development to completely rebuild India’s trust.

The relationship between India and China suffered gravely due to the bloody Galwan conflict of 2020, in which 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of PLA soldiers lost their lives in brutal, hand-to-hand combat.

The incident created unprecedented military build-up and new flash-points on the disputed border in eastern Ladakh. It also abruptly halted several institutional mechanisms that had been established to ensure normalcy and tranquility on the lengthy, treacherous border between the two countries.

Things appeared to be changing recently when Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi officially met with CCP leader Xi Jinping for the first time since the Galwan conflict. The two met in Russia on Oct. 23, on the sidelines of the BRICS summit.

The ten nation BRICS group—originally comprised of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—held its 16th annual summit in Kazan.

The two leaders “agreed to make good use of the Special Representatives mechanism on the China–India boundary question,” the Chinese Foreign Ministry said in a statement following the October meeting.

The special representative system between the two countries was established in 2003, after New Delhi and Beijing signed a declaration during then-Indian Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s visit to China.

The last special representatives’ meeting in 2019 in New Delhi also involved Doval and Yi.

The Indian national security adviser and the top Chinese diplomat, who were also present in Kazan as part of their respective delegations, thus met this week as special representatives of their states for the first time in five years.

“Both sides positively evaluated the solution reached between the two countries on border issues … and believed that the border issue should be properly handled … so as not to affect the development of bilateral relations,” the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement after Wednesday’s meeting.

Strengthening “the construction of the special representatives’ meeting mechanism” was one of the six points agreed upon by the two sides. They agreed to schedule the next round of meetings for next year in New Delhi.

The Impact of Trump 2.0

Experts told The Epoch Times that China decided to patch things up with India because it wants to focus fully on Trump’s second tenure.

Although Trump has extended an invitation to Xi for his second presidential inauguration, he has also repeatedly threatened to levy substantially higher additional tariffs on China.

Increasing geopolitical competition between the United States and China also implies Trump’s greater focus on China. This is already reflected in developments between India and China, they said.

“China is afraid of Trump because his policy between 2016 and 2020 was very strong against it,” Satoru Nagao, a nonresident fellow at the Washington-based Hudson Institute, told The Epoch Times.

Nagao said that the United States’ China policy remained consistent through the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations, and most likely will not change in the long term. However, the means employed by each administration varies. While Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden loved multinational frameworks, Trump prefers bilateral negotiations, he said.

He noted that in 2016, Trump invited Xi for a meeting and while the two leaders were eating dessert at the president’s Mar-a-Lago estate in Florida, told the Chinese leader that he had ordered missile strikes on Syria.

“This is effective intimidation, because this situation is unpredictable, and this is also a message to Xi that you could be [the] next target if [you] resist Trump,” Nagao said.

Many such actions are fresh in Xi’s memory, he added, as the communist leader prepares to confront Trump again.

U.S.–China competition looks to be the main topic under the new administration, Nagao said, pointing to Trump’s pick for secretary of state, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio—known for his outspoken attitude toward China.

Nagao also noted China’s plan to invade Taiwan in 2027, during Trump’s second administration.

Two weeks before the U.S. November elections, India and China announced an agreement to completely disengage militarily along their disputed border in eastern Ladakh. Two weeks afterward, India’s Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar met with Yi on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro.

The two discussed the resumption of direct flights between their countries—which had been suspended during the pandemic and never reinstated.

They also discussed a topic of tension, namely data sharing on trans-border rivers, which has been stopped on many occasions when border tensions rose.

Those points were reiterated in the consensus points reached on Wednesday.

In an interview following the Rio de Janeiro meeting, Nagao already told The Epoch Times that the India–China border agreement was a significant geopolitical development in the Indo-Pacific, triggered by the Chinese regime’s changing priorities in the region.

India is not currently an urgent matter for the CCP, he said, because it wants to focus on the new administration in the White House.

“China wants a cease-fire on the India–China border because it wants to concentrate on the Pacific side.”

Politics and Caution

According to analysts, while some progress is expected in bilateral ties between New Delhi and Beijing, nothing substantial is expected when it comes to border resolution, and India should remain cautious of Chinese maneuvers. The developments are time-specific and affected by various other geo-political factors, they say.

Beijing understands that its attitude toward India has limitations, said Anil Trigunayat, a former Indian diplomat and a distinguished fellow at the New Delhi-based Vivekananda International Foundation.

That attitude “is also limiting their outreach and initiatives in organizations like BRICS and [the Shanghai Cooperative Organization] let alone other geographies,” Trigunayat said.

Pant, a professor of international relations with the India Institute at King’s College, London, cautioned that the fundamentals of the Indo–China relationship are challenging, because the two countries remain so competitive.

The resumption of meetings under the special representative mechanism is a big change, Pant said, as China has traditionally used the border problem as leverage against India.

In some ways, it underscores “how China has been able to weaponize even basic negotiations on the boundary,” he said.

Those negotiations were put on the back burner after Galwan, and are now being resumed, and it is unlikely to make a major difference soon, Pant said.

“I don’t think we should make a big deal of it, because in that sense, this is just a restoration to status quo ante,” he said.

Trigunayat said that though Trump has threatened increased tariffs against India as well, the two countries share a global comprehensive strategic partnership, with bipartisan support.

“No doubt it will pose some challenges, but [the] Trump–Modi partnership and personal rapport will be able to weather those headwinds,” he said.

India’s “increasing global acceptability,” signaled by that partnership, has caused China to soften its posture toward India, Trigunayat said.