Lê Giang wrote this Vietnamese article, published in Luật Khoa Magazine on June 11, 2025.

Freedom of expression is widely recognized as a fundamental human right, enshrined in the constitutions of most nations—their social contracts; this principle holds true for Việt Nam as well. The history of legislating freedom of expression as a constitutional right within this nation reveals how it has been legally constructed and interpreted through various iterations over time.

Throughout its history, Việt Nam has adopted seven constitutions, each acknowledging freedom of expression to varying degrees. However, the interpretation and implementation of this right have evolved considerably, influenced by the nation’s changing political and historical contexts.

The treatment of freedom of expression in the constitutions of the Republic of Việt Nam is detailed in the following table:

Overall, the constitutions of the Republic of Việt Nam demonstrated a notable progression in recognizing and safeguarding freedom of expression.

The 1956 Constitution, established under the First Republic, acknowledged this right but imposed strict political constraints, prioritizing order over public dissent while still framing the State as the protector of truth in journalism.

By 1967, following political turmoil and the collapse of the family-run regime, constitutional thought shifted significantly. Freedoms of thought and the press were strengthened, censorship was curtailed, and legislative authority over the press was assigned to the National Assembly. Despite wartime limitations, these changes clearly indicated a movement toward the rule of law and democratic norms.

The 1946 Constitution stands as a historical landmark, not only as Việt Nam’s first constitution but also for its strong emphasis on civil liberties and progressive patriotism. Article 10 guaranteed a wide array of fundamental rights without reservation. Hồ Chí Minh notably declared, “The government is the servant of the people,” articulating a democratic vision where the state facilitates rather than restricts personal freedoms.

Consequently, the 1946 Constitution represents not merely a legal milestone but also a significant political and moral legacy—a fusion of national law and international democratic values.

From 1946 to 2013, freedom of expression in Việt Nam underwent significant transformation. While early constitutions embraced this right unconditionally, subsequent versions increasingly embedded it within various limitations and conditions. This evolution reflects a shift in the State’s approach to the citizen-state power relationship.

Later constitutions introduced qualifying phrases such as “in accordance with the interests of socialism” or “as provided by law,” which effectively curtailed the right’s substantive scope. This legislative trend, influenced by Marxist-Leninist ideology, subordinates individual freedoms to the demands of class struggle and revolutionary objectives.

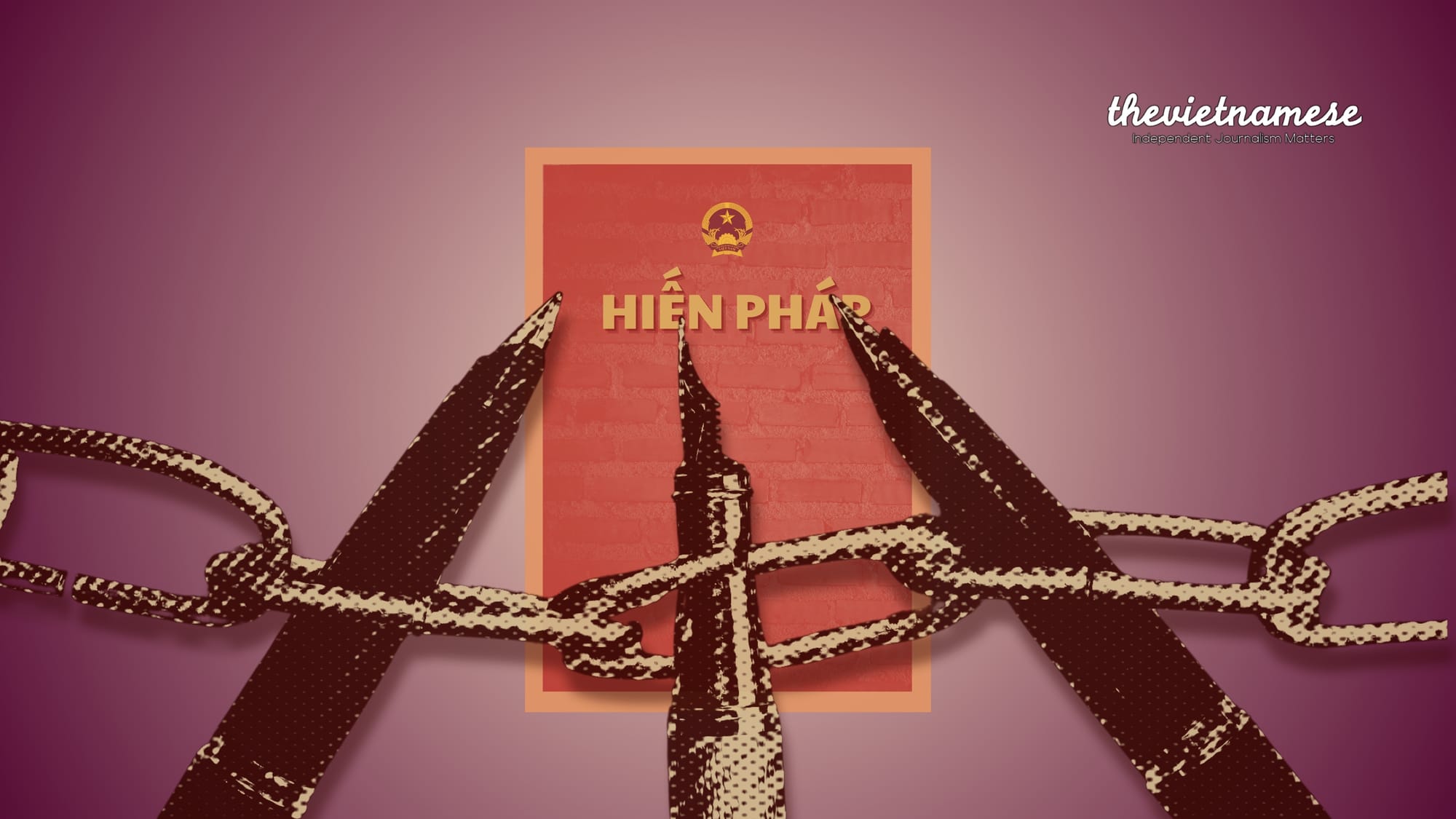

The 2013 Constitution is often cited as a step forward in Việt Nam’s constitutional system. However, its expansion of rights is often offset by vague legal provisions. The persistent use of the phrase “as provided by law” creates a legal gray zone, placing the actual realization of constitutional rights at the discretion of subordinate legislation.

To date, Việt Nam continues to lack key legislation, such as a Law on Demonstrations and a Law on Associations. Press freedom remains severely restricted, as all media outlets are state-owned and independent journalism is prohibited. Therefore, Article 25 of the 2013 Constitution, despite its progressive appearance, in practice serves as a mechanism to defer or undermine constitutional freedoms.

Furthermore, recent laws, including the 2018 Cybersecurity Law and the 2016 Press Law, have reintroduced stricter limits than even those outlined in the Constitution, particularly regarding state control over dissenting content and public discourse. In essence, while the 2013 Constitution displays nominal progress, it still embodies a formalistic resistance to genuine freedom of expression.

That is, while the right is formally recognized, its implementation remains entirely dependent on the political will of those in power.

In the last and final installment of this series, we will revisit freedom of expression in Vietnam through its three main avenues—the press, assembly, and protest—to better understand where the people’s right to raise their voices stands as the country enters a new era of ambition and transformation as stated by the Communist Party of Việt Nam.