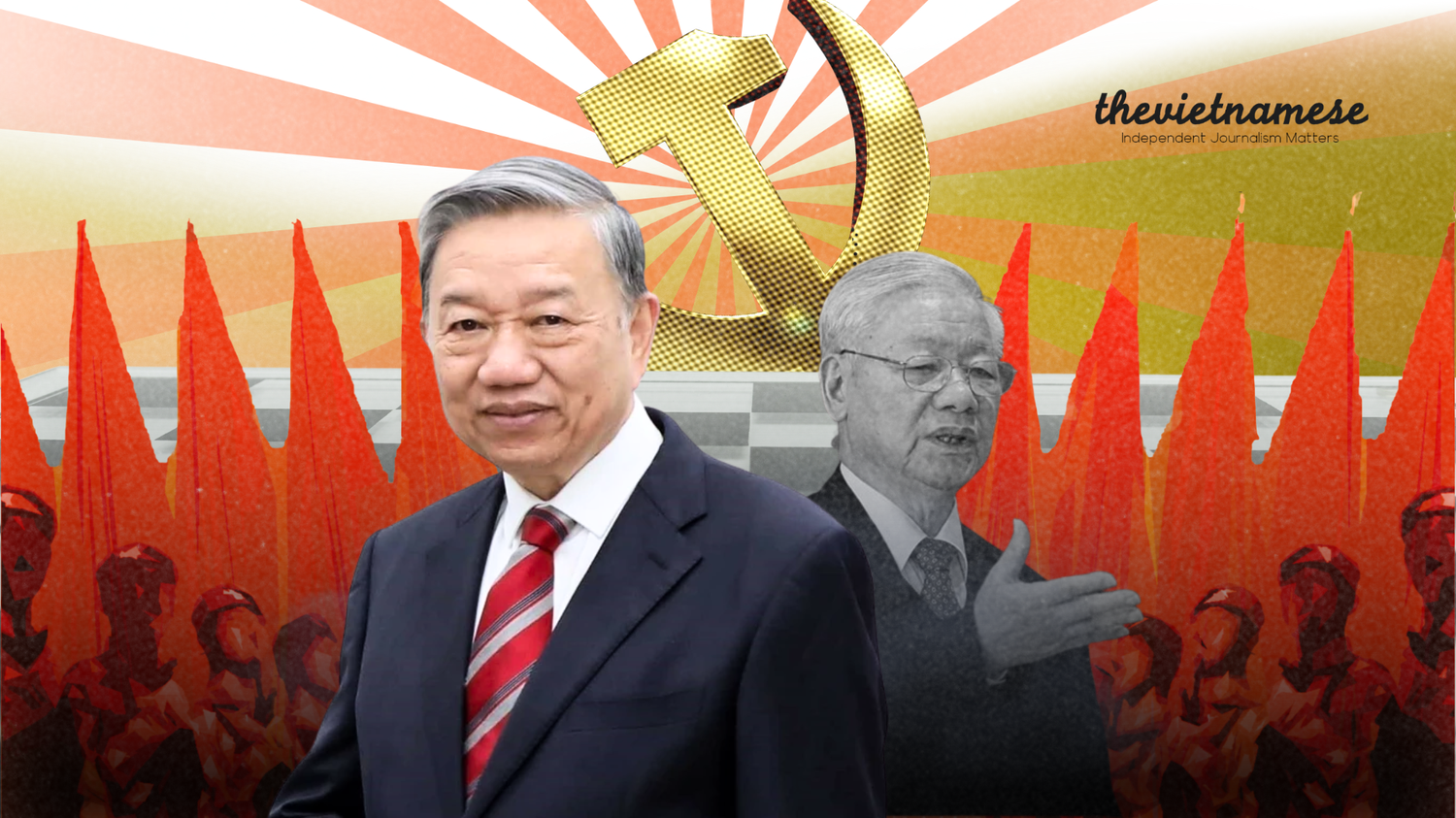

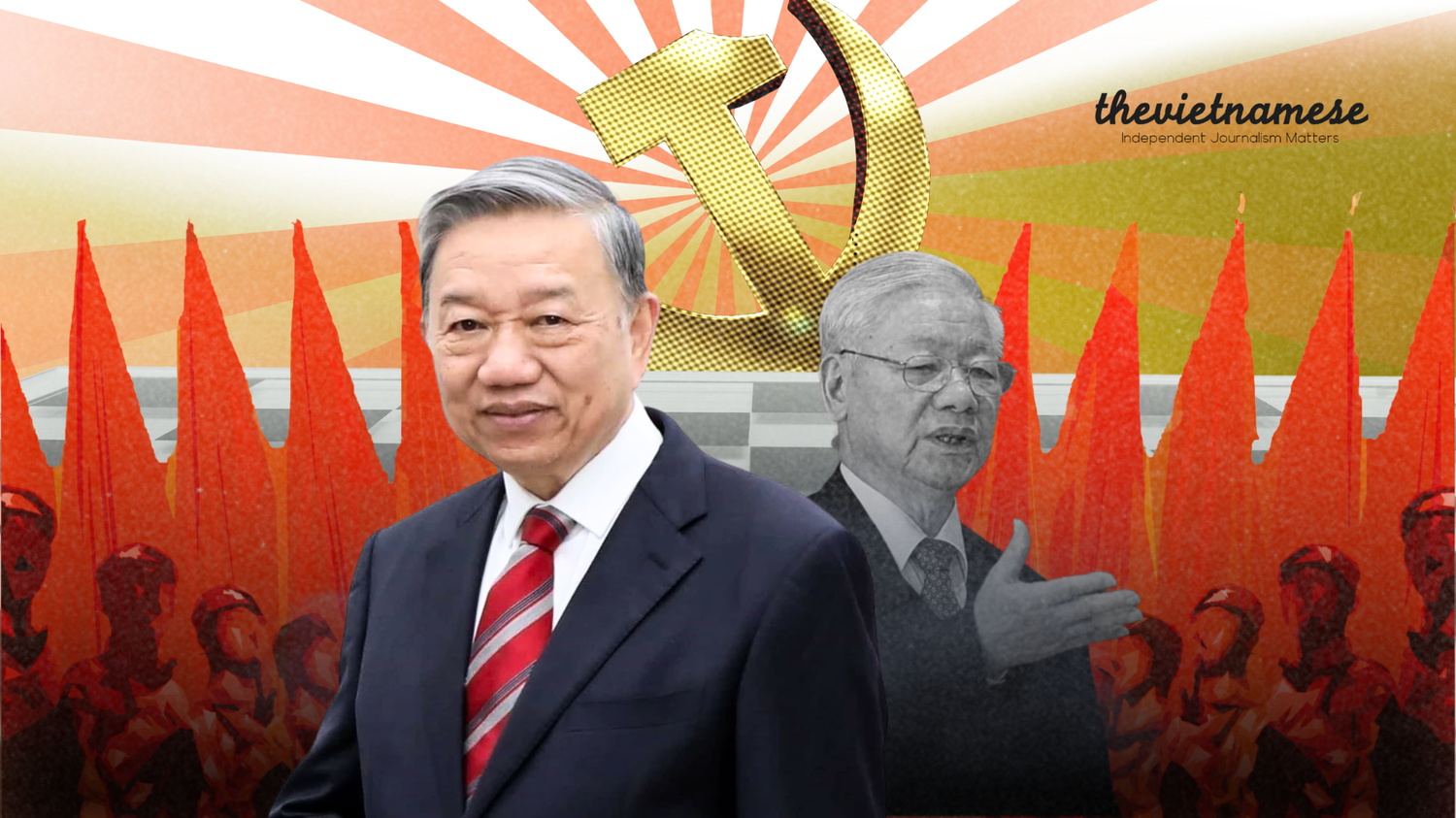

In 2021, Nguyễn Phú Trọng was re-elected as General Secretary of the Communist Party of Việt Nam for a third term at the age of 77. This decision occurred despite the fact that under the Party’s personnel regulations, the general secretary is normally limited to two terms and must comply with age requirements.

Nguyễn Phú Trọng clearly fell outside these parameters. If asked why this appointment was allowed, the Party’s answer comes in a single phrase: “a special case decided by the Party Central Committee.”

The phrase may sound innocuous, but it carries significant political weight. It not only serves to legitimize a specific personnel decision but also reveals how power operates within Việt Nam’s political system: rules exist, but they are not always absolutely binding.

The Ambiguity of the “Special Case”

The definition of a “special case” remains elusive. There are no clear criteria to determine when someone qualifies as “special,” nor is there clarity on whether such cases are straightforward or complex.

It is precisely this ambiguity that transforms the “special case” from a mere administrative exception into a tool of discretionary political power. Regulation 365 outlines dozens of criteria for the position of general secretary, ranging from political steadfastness and sharp thinking to leadership capacity and extensive experience. [1]

However, the final bullet point contains a line more consequential than all the strict criteria preceding it: “A special case as decided by the Party Central Committee.”

If “standards” represent the established rules of the game, the “special case” is the clause that permits mid-match rule changes, contingent only on the approval of the Central Committee.

The Advantage of Ambiguity

The Communist Party of Việt Nam has a history of semantic maneuvering. Throughout the country’s legal and political system, phrases are often deliberately constructed with such breadth that their scope remains impossible to pin down.

A clear precedent is Article 331 of the 2015 Penal Code. The provision’s vague wording allows authorities to expand the reach of social control at will. [2] The “special case” mechanism operates on the same principle.

These ambiguities are features, not flaws. In legal theory, they are known as open-textured provisions. [3] By preventing legal texts from having fixed, static meanings, these clauses grant interpretive authority to those in power. Whoever interprets the law ultimately decides the outcome. For the “special case,” this authority rests exclusively with the Party Central Committee.

Defining a “special case” clearly would invite difficult scrutiny: Why does one case qualify while another does not? Ambiguity sidesteps these questions entirely.

Because each Party Congress occurs in a unique context, a rigid definition today could tie the Committee’s hands tomorrow. Maintaining ambiguity ensures that the party retains the initiative and flexibility to make personnel decisions as it sees fit.

The Necessity of the Broad Clause

When is someone considered a “special case”? The answer is simple: when the Party Central Committee deems it necessary. This necessity may stem from a need for stability, continuity, internal balance, or the aversion of internal struggles hidden from the public eye.

Scholars note that senior personnel decisions in Việt Nam do not follow the logic of competitive selection or résumé comparisons. Instead, they follow the logic of internal consensus. Professor Carlyle A. Thayer describes this process as a mechanism for legitimizing political bargains, where the “special case” label serves as the official stamp on a collective decision. [4]

Reinforcing this view, political scientist Nguyễn Khắc Giang and his colleagues at ISEAS argue that the Party Central Committee has evolved into the true center of gravity for personnel organization in Việt Nam. This body actively decides who enters the top leadership ranks and under what arrangements. [5]

The Central Committee’s authority to designate a “special case” is a manifestation of the power the body has effectively always held.

The Person Before the Rule

Nguyễn Phú Trọng’s third term serves as the clearest illustration of a specific political logic: the person arrives first, and the standards follow.

At the time of his re-election, many other candidates technically met the written criteria—they were younger, qualified, and capable. However, maintaining safety and internal harmony were the deciding factors in lieu of compliance with these criteria. The Party required a leader safe for the political line, the existing arrangements, and the delicate balance of power among elite factions.

On paper, standards ostensibly select the candidate. In practice, the candidate is selected, and the standards are adjusted—or invoked—retroactively to legitimize the choice. While standards still function to filter out weak or risky options, at the highest levels they are merely relative reference points rather than absolute constraints.

This dynamic aligns with Milan W. Svolik’s analysis of authoritarian regimes, which suggests that personnel rules are designed less for administrative order and more for managing competition among elites. [6] Regimes survive by controlling internal conflict, often prioritizing stability over rigid adherence to written rules.

The “special case” is the instrument that formalizes this priority.

As the 14th National Congress intensifies, the “special case” provision will likely be utilized again. This leaves us with a critical question: if exceptions are now a permanent feature of the game, do the standards and regulations carry any remaining weight?

Thúc Kháng wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on Dec. 17, 2026. The Vietnamese Magazine has the copyrights for its English version.

References:

- See: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/phap-luat/ho-tro-phap-luat/tong-bi-thu-moi-chu-tich-nuoc-moi-thu-tuong-chinh-phu-moi-chu-tich-quoc-hoi-moi-theo-quy-dinh-365-3-408001-246331.html

- Trịnh Hữu Long. (2025, July 12). Tội lợi dụng các quyền tự do dân chủ – một điều luật hoàn toàn thừa thãi. Luật Khoa Tạp Chí. https://luatkhoa.com/2022/03/toi-loi-dung-cac-quyen-tu-do-dan-chu-mot-dieu-luat-hoan-toan-thua-thai/

- Review: [Untitled]. (1963). The Philosophical Review, 72(2), 250–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2183110https://www.jstor.org/stable/2183110

- Minh Viễn. (2025, November 27). Bầu tổng bí thư Đảng Cộng sản Việt Nam: Ba điều cần hiểu. Luật Khoa Tạp Chí. https://luatkhoa.com/2025/10/bau-tong-bi-thu-dang-cong-san-viet-nam-ba-dieu-can-hieu/

- NGUYEN KHAC GIANG, NGUYEN QUANG THAI. (2022). From periphery to centre. Contemporary Southeast Asia, 44(1), 56–86. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27130808

- Svolik, M. W. (2012). The politics of authoritarian rule. In Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9781139176040