Medicaid, the state and federal program that provides health coverage for millions of low-income Americans, has taken center stage in Congress’s bid to pass President Donald Trump’s sweeping agenda.

In simplest terms, Republicans want to reduce the cost of the $816 billion program as part of a long-term plan to cut federal spending and implement Trump’s tax cuts and his border and energy measures.

Democrats adamantly oppose cuts to the program.

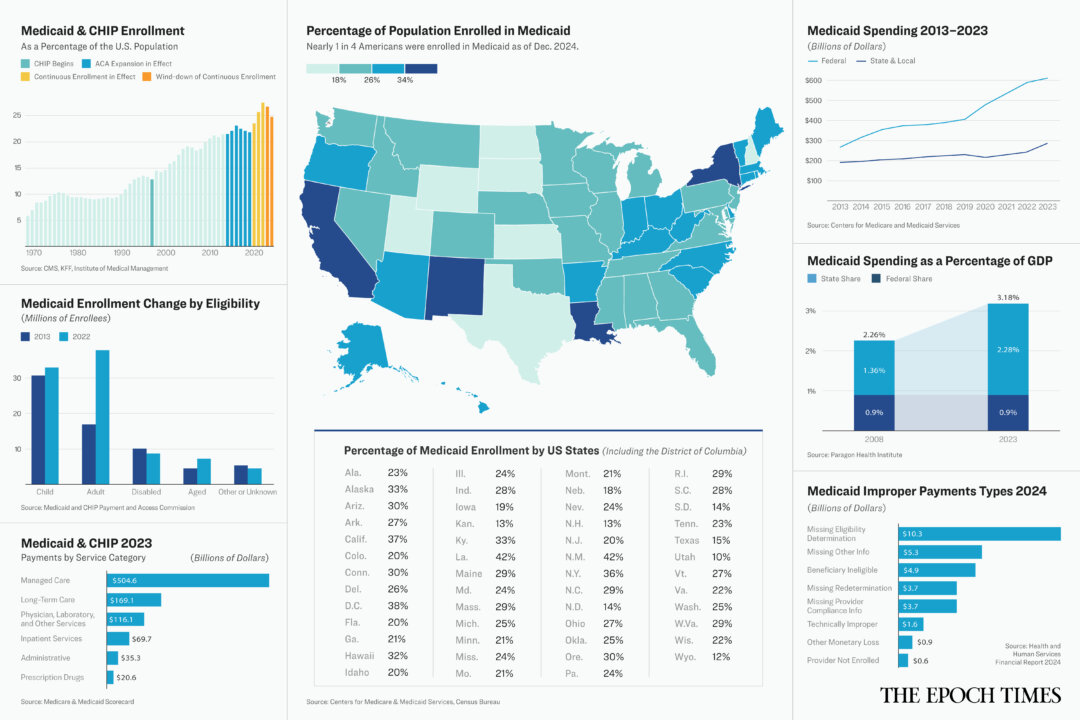

Though nearly one in four Americans is covered by Medicaid, many people seem to know little about the program or how it works.

Here are the basics of this complex system, which was created in 1965 and has been altered several times since.

What Is Medicaid?

Medicaid is a program that provides health coverage for lower-income Americans, underwritten by state and federal tax dollars. About 85 million people were enrolled in the program as of December 2024.

Medicaid is operated by the states but overseen by the federal government. No state is required to participate in Medicaid, though all states have chosen to do so.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services oversees the program on the federal level, but each state has its own Medicaid office. Some states refer to Medicaid by a different name. In California, it’s known as Medi-Cal. In Oklahoma, Medicaid is called SoonerCare.

Medicaid is not the same as the Children’s Health Insurance Program, usually called CHIP. However, the two are similar and are usually considered together.

CHIP was started in 1997 to cover medical costs for uninsured children and pregnant women whose income is too high to qualify for Medicaid but who still have trouble affording health insurance.

Who Can Get Medicaid?

Original Medicaid covers low-income people in certain categories including children, pregnant women, parents of dependent children, the elderly, and people with disabilities.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) expanded Medicaid eligibility in 2014 to include most people who are under age 65 and who earn at or below 133 percent of the federal poverty line. That’s about $22,000 for an individual or about $42,000 for a family of four including two children.

Forty states and the District of Columbia have chosen to provide this expanded coverage.

The income threshold for CHIP eligibility varies by state and ranges from 170 percent to 400 percent of the federal poverty line.

Medicaid enrollment grew to a high of 94.6 million in April 2023 when states were required to maintain the “continuous enrollment” of nearly all Medicaid beneficiaries during COVID-19 regardless of their eligibility status. Under the Families First Coronavirus Response Act of 2020, Medicaid coverage could not be discontinued unless the enrollee requested it, moved out of state, or died.

That provision expired in March 2023, but due to the large backlog of eligibility recertifications to be processed, states have had some flexibility in winding down their continuous enrollment. The deadline for all states to comply with Medicaid and CHIP eligibility requirements is Dec. 31, 2026.

What Does Medicaid Cover?

Medicaid coverage varies from state to state and depends on the eligibility category of the person enrolled.

Traditional Medicaid programs are required to cover some basic services including hospital stays, doctor visits, and nursing home care. Beyond that, states can choose to cover a variety of services including personal care, prescription drugs, and physical therapy.

A second type of coverage known as the Alternative Benefit Plan is usually required for people who enrolled in Medicaid under the ACA expansion. Under the alternative plan, coverage must include the essential health services covered by most private health insurance plans.

Who Pays for Medicaid?

Everyone pays for Medicaid through tax dollars. In some states, beneficiaries pay part of the cost through copayments for certain services.

Each state sets the reimbursement rates for its Medicaid program. States pay providers or managed care organizations to treat their beneficiaries.

States can use a traditional fee-for-service system, in which they pay a doctor or other provider for each service provided to a patient.

Or they can use a managed care system, which pays an annual amount for each beneficiary to a managed care organization, which must then pay for all the covered services the beneficiary needs.

Most states use both systems.

The federal government then reimburses each state a certain portion of the amount it spends on Medicaid.

The reimbursement rate varies by state and is determined based on the income level in the state. The reimbursement rate currently ranges from 50 percent to 83 percent of the amount spent on Medicaid.

The total cost of Medicaid and CHIP in 2023 was $896 billion. About 70 percent of that amount, $616 billion, was paid by federal taxpayers. The rest was paid with state taxes.

Medicaid beneficiaries may have to pay copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles. The amount of those fees varies by the patient’s income.

Why Do Some Want to Cut Medicaid Spending?

Under the plan to implement Trump’s agenda, House Republicans intend to reduce federal spending by at least $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years.

A recently passed budget blueprint directs the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, which oversees Medicaid, to find $880 billion in cuts.

According to data from the Congressional Budget Office, Medicaid accounts for 93 percent of the spending overseen by the Energy and Commerce Committee.

Trump and House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) have consistently said they will reduce Medicaid spending by eliminating fraud and abuse but will not cut benefits.

Democrats have said that the program does not contain enough fraud and waste to produce the savings Republicans want. They have urged Republicans not to consider cutting the program.

How Much Does Medicaid Lose to Fraud?

The Government Accountability Office has estimated that the federal government may lose between $233 billion and $521 billion annually to fraud.

Based on data provided by that office, it appears that less than 3 percent of the estimated total of fraudulent payments are proven by a judicial verdict. Much of it appears to go undetected.

Yet fraud does exist in the Medicaid system.

One state lost an estimated $2 billion to Medicaid fraud over the past five years, a staff member in that state’s attorney general’s office told The Epoch Times.

The Department of Health and Human Services reported that more than $31 billion in Medicaid payments were made improperly in 2024 alone.

Of those, nearly $5 billion was paid for medical services for patients who were not eligible for Medicaid, and more than $10 billion was paid for claims where no eligibility information was provided.

Medicaid Fraud Control Units recovered $1.2 billion in 2023, which was more than three times the amount spent on fraud enforcement efforts, according to the Office of Inspector General. Investigators said they could eliminate more fraud if more funding for enforcement activities were available.

Is There Any Other Way?

Dr. Mehmet Oz, the administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, told senators during his confirmation hearing that he would improve Medicaid’s efficiency.

Oz referred to ideas for using artificial intelligence to make prior authorization decisions for medical procedures more quickly and require less physician interaction and by using communications technology to allow nurses to provide remote support to rural nursing home staff members.

A frequently raised suggestion for reducing federal Medicaid spending would involve lowering or eliminating the taxes some states levy on medical providers.

These provider taxes, used by every state but Alaska, help fund states’ Medicaid expenses. The taxes are generally returned to the providers through increased payments for Medicaid services.

However, the increased payments to Medicaid providers then increased the federal reimbursement received by the state. The arrangement effectively shifts more of the financial burden of Medicaid to the federal government.

The Congressional Budget Office, which provides nonpartisan financial assessments to Congress, estimated that eliminating the provider tax would reduce the federal deficit by $612 billion over 10 years, or as much as $241 billion if the tax rate were limited to 5 percent.

Others have suggested setting a per-capita cap on the amount the federal government would reimburse states for Medicaid.

Altering the provider tax or setting a per-capita cap on reimbursement would save federal dollars but would almost certainly increase the cost of Medicaid to the states.

Some experts, including Leonardo Cuello, a research professor at Georgetown University, think that would force states to reduce eligibility, coverage, and provider payments.

Congress returns on April 28 to consider a budget reconciliation bill. Medicaid funding is likely to figure prominently in the discussion.