In an interview with the Post published last month, Columbia University professor Jeffrey Sachs said the war in Ukraine could end “tomorrow” through diplomacy.

He said the underlying cause of the conflict was Nato’s enlargement drive since the 1990s to include Ukraine and Georgia, and he maintained that peace could be restored only by removing that cause.

Sachs has been widely respected for decades but differs from mainstream Western media on many issues, including this view of the war.

Some Western analysts and politicians argue that enlargement of the transatlantic security alliance was just an excuse for Russian President Vladimir Putin to invade Ukraine.

They argue that Russia started the war in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea, part of Ukraine at the time, and the invasion by Russian troops in 2022 was an escalation of the ongoing conflict.

For years, Nato members were divided about whether to include Ukraine. There were also efforts to try to “neutralise” Ukraine – or ensure it was neither a Nato nor Russian proxy – by finding ways to guarantee its security without making it part of the alliance.

For example, retired French diplomat Maurice Gourdault-Montagne, who was a senior diplomatic adviser to French president Jacques Chirac, said the failure to set up a Nato-Russia Council in 2002 was a “missed opportunity” to neutralise Ukraine.

Of course, with the animosity now between Nato and Russia, even Gourdault-Montagne says the time for collaboration is over.

But that does not mean the main players should give up efforts to resolve the crisis through diplomacy. It will, however, require the right timing, skills, and the removal of the biggest obstacle for peace talks: Nato membership for Ukraine.

Nato says that each country has the right to make its own security choices, and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has repeatedly appealed to the alliance to give his country full membership.

That is something Putin is unlikely to ever accept, with his security concerns outweighing the cost of the war to his country.

Putin insists that a ceasefire can only happen if the areas occupied by the Russian military are accepted as his country’s new frontiers and if Ukraine is ruled out of Nato membership. Ukraine, meanwhile, demands the withdrawal of Russian troops from Ukraine, including Crimea.

However, as the dynamics of the war change, the frontiers may not be entirely non-negotiable for Russia – unlike the Nato membership issue.

Some analysts argue that Russia has always seen Ukraine as part of its “kingdom” and would not tolerate a pro-Western government in Kyiv.

But the fighting in the last two years shows that the “annexation of Ukraine”, whether that was Putin’s original goal, would not be possible.

The resilience of Ukraine also shows that it does not necessarily take Nato membership for Ukraine to remain independent.

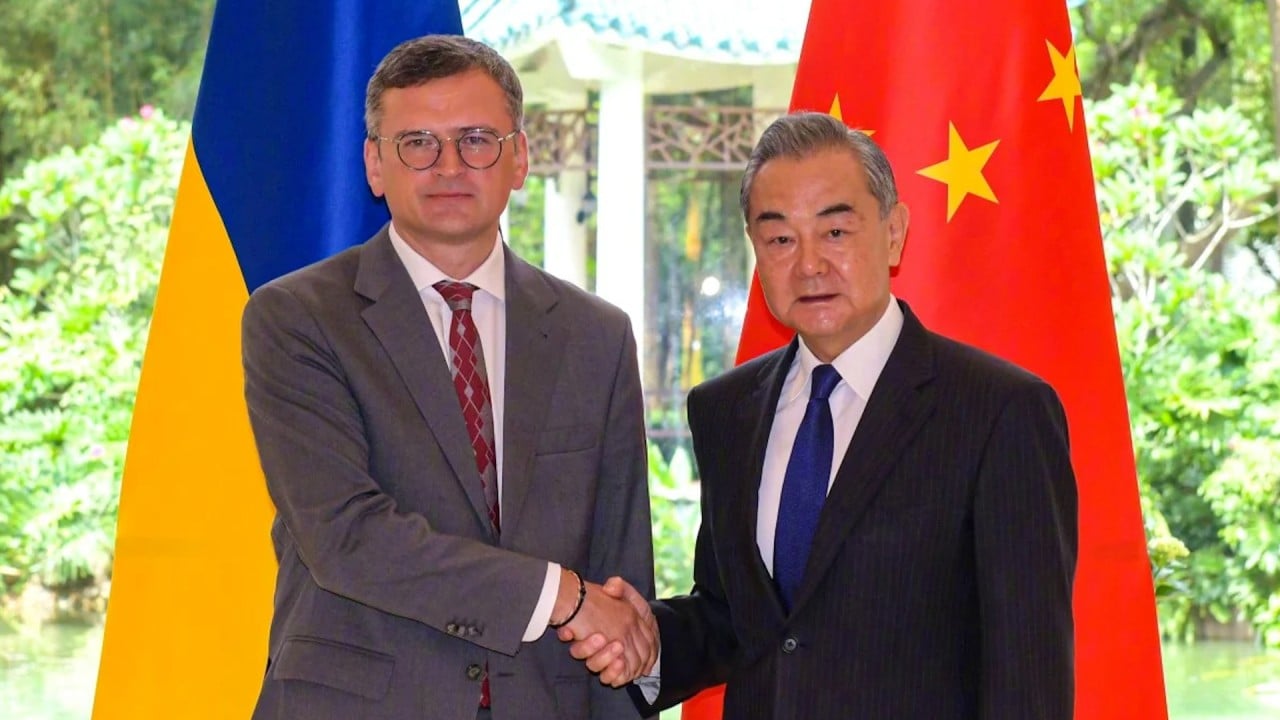

Beijing has repeatedly said it is willing to help mediate a way forward, offering a six-point ceasefire proposal. But the plan was vague and its suggestion to host a peace conference between Russia and Ukraine also failed to gain any traction.

Western governments see Beijing as siding with Moscow and accuse it of helping Russia to circumvent Western sanctions. Nato went so far as to call Beijing a “decisive enabler” of Russia’s war on Ukraine, a claim Beijing rejected as groundless.

Not all mediators have to be neutral. Sometimes a sympathiser plays a better role as the mediator because it has the trust of a certain party.

In that sense, Beijing, with its close ties with Moscow, can still play its part. Of course, the support from the United States and the European powers will also decide how long Ukraine can hold off Russia.

Resolution of the conflict depends on two big questions: does Putin want an exit from the war and can Ukraine’s Western allies offer it protection other than full Nato membership?

If yes and yes, then it is not totally impossible to reach a settlement.