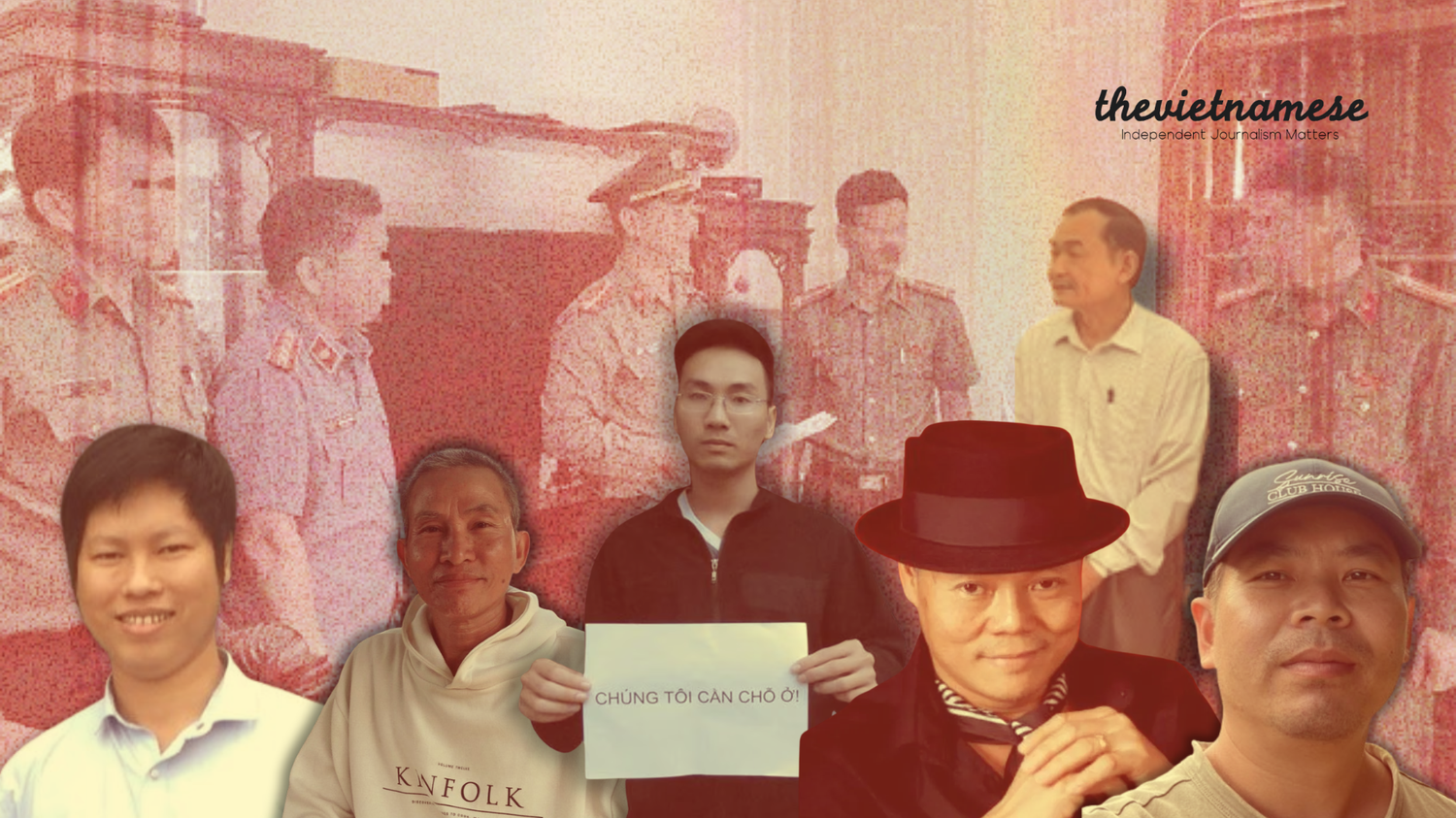

CIVICUS Monitor has released further updates on the state of freedom of expression and association in Việt Nam for the second half of 2025. Despite a formal review by the UN Human Rights Committee (CCPR) in July, the Vietnamese government has only accelerated its campaign against perceived dissent.

The subsequent months have been defined by a fresh unrelenting wave of arrests targeting activists, journalists, religious leaders, and land rights defenders. Those working with ethnic minorities or on environmental issues have also been silenced under the regime’s preferred tools: vague national security laws under the 2015 Penal Code, particularly Articles 116 (“undermining national unity”), 117 (“propaganda against the state”), and 331 (“abusing democratic freedoms”).

CIVICUS, an international alliance dedicated to strengthening citizen action, continues to rate the civic space in Việt Nam as “closed,” a designation the country has held for seven consecutive years.

This new crackdown follows a relentless first half of the year. The period from January to June 2025 saw authorities target religious and minority leaders, including Protestant pastor Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng (arrested in January 2025) and Khmer Krom advocates Venerable Kim Som Rinh, Thạch Nga, and Thạch Xuân Đồng (arrested in March 2025). The government also handed prominent activist Trịnh Bá Phương his first new charge—spreading anti-state propaganda—while he was already in prison. In a move that shocked the international community, the Ministry of Public Security officially designated the respected refugee aid organization Boat People SOS (BPSOS) as a “terrorist” group. The sentencing of independent journalist Trương Huy San (Huy Đức) and the banning of The Economist for its cover art, also culminated in a nationwide block of the messaging app Telegram in June.

The second half of 2025 illustrates a continuation of Việt Nam’s actions.

Latest Developments in Freedom of Association

Việt Nam’s assault on freedom of association intensified after the UN review, targeting any individual perceived as a threat to the state’s prevailing narrative.

CIVICUS notes that the new wave of persecution began with the detention of activist Hồ Sỹ Quyết in Hồ Chí Minh City on Aug. 28, 2025. His wife, Trần Ngọc Trâm, later reported that her last contact with him was a brief call at 9:30 p.m. that same day, when he managed to say, “I’m at the police station,” before the line was cut. When she was able to confirm his location at the 258 Nguyễn Trãi Police Station, she was denied permission to see him and received no explanation for his arrest. On Sept. 19, she learned that her husband was charged with “spreading propaganda against the state” under Article 117 of the 2015 Penal Code.

Days later on Sep., human rights activist Lý Quang Sơn (Trần Quang Trung) was arrested and detained while “illegally infiltrating” across the border of Việt Nam and Cambodia.” He was accused of being a member of the overseas Viet Tan—a U.S.-based Vietnamese political organization labeled a “terrorist group” by Hà Nội.

The crackdown on land rights has also escalated. Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that on Oct. 6 and Oct. 8, 2025, police in Gia Lai Province arrested the land rights activist Võ Thị Phụng and her accomplice, Nguyễn Văn Tông. Authorities charged both with “abusing the rights to freedom and democracy to infringe upon the interests of the state” for opposing a groundbreaking ceremony at an industrial park; confiscated land was allegedly used for its development.

Religious figures that operate outside the state’s strict control remain a primary target, as reported by CIVICUS. On Oct. 8, 2025, the Security Investigation Agency of the Đắk Lắk Provincial Police detained Y Nuên Ayun, a Montagnard pastor. He was charged under Article 116 of the 2015 Penal Code for “undermining the policy of national unity,” for his involvement in the Evangelical Church of Christ in the Central Highlands. This organization has often been targeted by police for illegally operating and not being officially sanctioned by the state.

Land rights defender Trịnh Bá Phương, who was already serving a 10-year prison sentence beginning in 2021 for spreading anti-state propaganda, was handed a second conviction and prison sentence in September 2025. This new charge stemmed from an incident in November 2024, when police allegedly found pieces of paper in his prison cell with the slogans “Down with the Communist Party that Violates Human Rights” and “Down with the Court that Convicted Me.” During this trial, Trịnh Bá Phương’s lawyers were not allowed to present their case, and he himself was not allowed to make his final statement; neither his family members nor foreign diplomats were allowed to attend the hearing.

Latest Developments in Freedom of Expression

Alongside the crackdown on association, Việt Nam has waged a parallel war on free expression, targeting the few independent journalists and bloggers still brave enough to operate.

In the CIVICUS update, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reported that authorities issued an arrest warrant on Aug. 14, 2025, against Đoàn Bảo Châu for “propagandizing against the state.” Châu, a freelance photographer and reporter for several international news outlets, currently communicates information via his personal Facebook page, which has over 200,000 followers. On July 3, 2025, over 20 officers raided his home in Hà Nội and charged him under Article 117.

CIVICUS also notes the arrests of independent journalist Huỳnh Ngọc Tuấn, alongside a blogger, Nguyễn Duy Niệm, in October 2025. Both individuals were charged with “conducting propaganda against the state,” under Article 117 of the Penal Code. Prior to this current arrest, Tuan, who received Human Rights Watch’s Hellman/Hammett Award, had been previously imprisoned for 10 years. Niem was accused of being affiliated with the Collective for Democracy and Pluralism, a pro-democracy group founded in France.

To formalize its absolute control over information, the National Assembly’s Standing Committee proposed amendments to the Press Law on Oct. 8, 2025. A controversial new clause introduces a provision that would “[empower] chief investigators of the Ministry of Public Security and provincial police to request that news organizations or journalists disclose the identities of their information sources for use in criminal investigations, prosecutions, or trials.”

CIVICUS mentions that, if passed, this would negatively impact any remaining press freedom and journalistic independence in the country; this would challenge the principle of source protection that underpins investigative reporting, effectively dismantling it by law.

Latest Developments in Peaceful Assembly

Finally, CIVICUS briefly tackles the UN Human Rights Committee’s July 2025 findings that directly addressed the state of peaceful assembly in Việt Nam, noting several issues about the “excessive restrictions” imposed on public meetings. The Committee was particularly concerned about the application of Prime Minister Decision No. 06/2020, which requires advance government approval for any public events related to human rights. The Committee also noted reports of “disproportionate use of force and arbitrary arrests” by law enforcement to disperse peaceful assemblies.

The arrests of Võ Thị Phụng and Nguyễn Văn Tông in October for protesting land confiscation serve as a clear and immediate rejection of the Committee’s recommendations.

Conclusion

It has been seven years since CIVICUS first rated Việt Nam’s civic space as “closed.” The events of 2025—from the “terrorist” designation of BPSOS in February to the prison trial of Trịnh Bá Phương in September and the proposal of a new, draconian press law in October—only prove that the government is committed to continuing its streak of intensifying human rights violations.

Việt Nam is waging a war of attrition against activists on the ground while simultaneously ignoring and defying the formal recommendations of UN human rights bodies, a reflection of the deep-seated insecurity festering at the heart of the one-party state.

The government still appears to operate under the belief that if it jails enough journalists, intimidates enough pastors, and sentences activists to terms so long that they are functionally erased from public life, it can achieve lasting “stability”. But the UN’s own findings and the continued courage of individuals like Võ Thị Phụng and Huỳnh Ngọc Tuấn offer a different, more pointed lesson. “A fortress built on silence is, ultimately, a fortress built on sand.”

As the second half of 2025 has shown, the regime is now frantically trying to outlaw the tide itself.