Chinese scientists say they have come up with a method to extract water from the moon’s soil – a potentially vital step towards building a lunar research base.

The technique depends on extracting hydrogen and oxygen from the soil at extremely high temperatures, and was described on Thursday as “highly practical” by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS).

The search for water has long been one of the top priorities for lunar exploration missions, but previous efforts had focused on the search for natural water reserves.

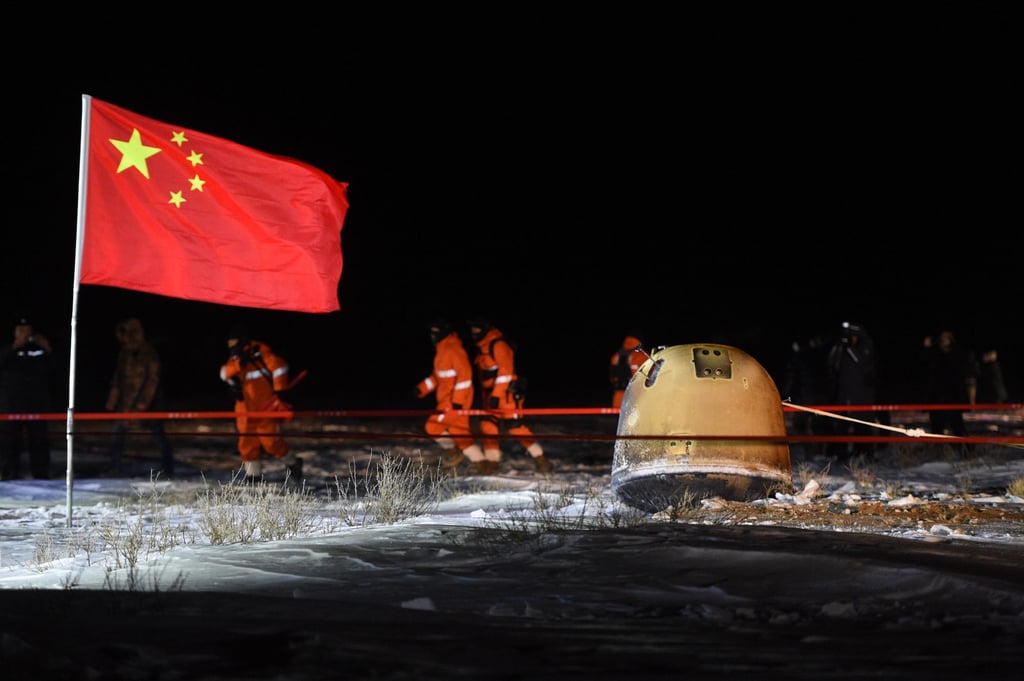

But researchers from the Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, the CAS Institute of Physics and other institutions came up with the new method after studying lunar rocks brought back to Earth by China’s Chang’e-5 probe in 2020.

The team found that some of the minerals in lunar soil – especially the oxide mineral ilmenite – store large amounts of hydrogen as a result of billions of years of exposure to the solar wind.

When heated, the hydrogen chemically reacts with iron oxides in the minerals to produce large amounts of water, as well as iron and ceramic glass.

Then, when the temperature passes 1,000 degrees Celsius (1,832 Fahrenheit), the lunar soil itself will start to melt, releasing the water in the form of a vapour.

The team said they had studied the lunar soil using techniques such as high-resolution electron microscopy and concluded that 1 gram of lunar soil would produce about 51 to 76 milligrams of water.

This means that a tonne of lunar soil could produce about 50 litres (13 gallons) – “basically enough for 50 people to drink in a day”, the academy said.

Based on these findings, the team proposed a method of heating the lunar soil until it melts by focusing sunlight through concave mirrors.

The researchers said that the iron produced as a by-product of this process could be used as a raw material for making electronic equipment on the moon, while the melted lunar soil could be used as a construction material for a base.

But they also warned that subsequent Chang’e lunar missions would have to carry out further feasibility checks to see if this technique can become a reality.

The academy said: “This method is highly practical and is expected to provide a design basis for the construction of future lunar research stations and space stations.”

The study was published on Thursday in The Innovation, an English-language, peer-reviewed academic journal founded by a group of young Chinese scientists in 2020, which has become one of the world’s top multidisciplinary publications.

The search for water on the moon has been a decades-long quest for lunar scientists, who now believe that ice may exist in its natural state at its south and north poles, as well as in areas that lie in perpetual shadow.

The samples brought back from Chang’e-5 have shown that some minerals in the lunar soil – including glass and pyroxene – contain small amounts of water.

A separate analysis of those samples – published in the journal Nature Astronomy last month – detected a hydrated mineral “enriched” with molecular water.

But the Chinese Academy of Sciences warned on Thursday that the water content of these minerals is very sparse, ranging from 0.0001 to 0.02 per cent, making it difficult to extract and use them.

A variety of missions in the next few years will continue the hunt for water on the moon, including Russia’s Luna 26 orbiter and China’s Chang’e-7 mission, which is scheduled to launch around 2026 and will land on the lunar south pole.

Meanwhile, Nasa’s efforts suffered a setback last month when the Viper lunar rover was cancelled on cost grounds, but the agency said it will continue the search by other means.

Beyond the immediate benefits to lunar missions, a recent article in the Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences said lunar water resources could one day be used as a fuel source for vehicles involved in deep space missions by breaking them down into oxygen and hydrogen.

The article, written by researchers from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics, added that the search could also help reveal key processes in the formation and evolution of the Earth and moon, and even the wider solar system.