In July, senior executives from Midea, a leading Chinese consumer-electronics brand, travelled to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to host a recruitment event amid the company’s push to localise operations and boost its American presence.

The event at one of the world’s most renowned research centres saw Midea’s top managers sharing stories of personal growth and inviting jobseekers to explore opportunities in the US, the company’s second-largest market.

But the nearly 100 prospective job applicants, mostly mainland students attending universities in greater Boston, bore a more pressing concern: how was the firm navigating a politically hostile terrain for Chinese businesses?

The question and the challenges it encompasses have vexed countless mainland companies and prospective employees alike.

One Boston University student asked if Midea planned to set up a manufacturing plant in the US given the rising zeal of “Made-in-America” branding.

Another asked how the company protected customers’ personal data or if it planned to build a local data centre. Several said they were looking for jobs in Asia – not stateside.

The concerns loomed “because the US government is always worried that Chinese companies take data from the US and that it’s a safety risk”, explained an attendee who asked not to be named.

Another admitted: “I am seeking a job in Midea working in China because it’s a large company, perhaps because it will be more secure.”

Their preoccupations reflect hardening attitudes about China in the US, where some lawmakers and regulators deem the popular short-video app TikTok owned by mainland-based start-up ByteDance a dire threat.

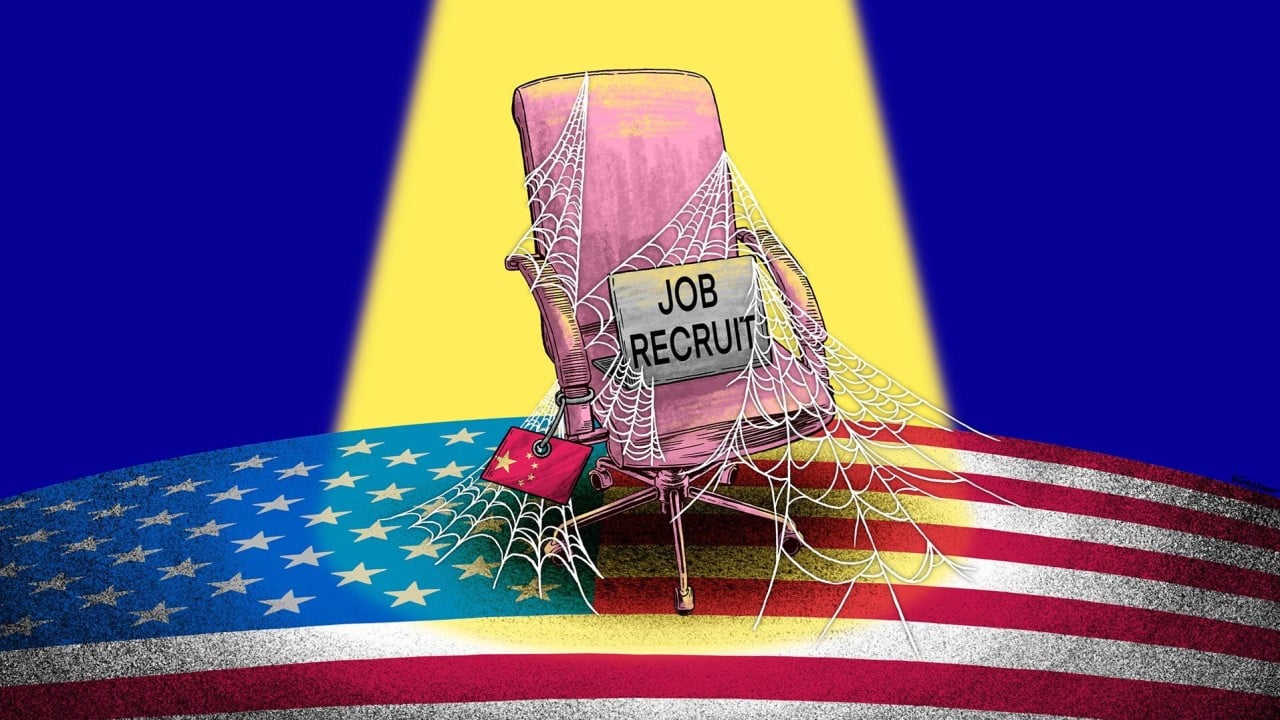

As politicians raise national security fears and accuse Chinese companies of taking American jobs, the stigma has ensnared lower-profile firms.

Apprehensions are increasingly widespread for those seeking to localise operations and lure talent in the US, experts observe, and differences in management style can complicate retention.

Midea, a Fortune 500 company whose market capitalisation exceeds US$60 billion, is a major manufacturer of air conditioners, microwaves, refrigerators and other home appliances. Its production facilities can be found in Brazil, India and Vietnam.

However, high production costs leave it reluctant to open factories in North America. That is despite Midea’s US revenue surging from under US$100 million in 2015 to over US$1 billion in 2021, according to a 2022 Forbes interview with Kurt Jovais, the firm’s then president of American operations. Its global revenue totalled about US$53 billion in 2023.

In 2022, some 173 staff worked at Midea’s New Jersey headquarters and plans are afoot to grow that figure next year by 20 per cent. Last month, the company announced its R&D facility in Kentucky would expand with 110 new jobs “over the coming years”.

Globally, Midea has more than 30 R&D centres. Yet a representative, speaking on the condition of anonymity, called attracting top talent in the US its “biggest bottleneck”.

“When you’re localising staff, there’s going to be challenges, whether you’re famous or not,” the company representative said, adding that the strategy was to “localise as much as possible” and offer more salary and opportunities “than average”.

Midea is not alone among Chinese firms confronting steep hurdles to US expansion.

A senior official at REPT Battero, a mainland renewable battery maker whose American operations commenced in 2022, said its hiring was sluggish.

“We have 10 local people in the US and we are planning to increase our team to 25 to 30, but it’s very difficult,” said Jason Hong, the company’s US general manager.

Having looked “for several months”, Hong voiced frustration over the time needed to interview candidates, saying recruitment agencies were expensive.

In response, REPT’s US-based sales and technical roles now require fewer years of prior work experience.

Chris Pereira of iMpact, a New York-based consultancy, believed professional hazards befell American applicants, especially “if it’s a government relations role or a public affairs role”.

“There could be some reputational risk or even legislative risk in the future if you’re working for a Chinese company,” Pereira said.

Julian Ha of Heidrick & Struggles, a Washington-based executive recruiter, attested to a shift in sentiment from “10 to 15 years ago”.

Before, “executives would reach out to us”, Ha said. “That’s certainly not the case any more. It’s we who actually have to really actively recruit people.”

Isaac Stone Fish of Strategy Risks, a company that analyses corporate exposure to China, contended Americans contemplating such employment must consider risks like sanctions, legal issues and reputational damage.

“The negative press some US government officials have received because they had previously lobbied or advocated for Chinese companies certainly discourages others to follow in their path,” he said.

A China General Chamber of Commerce survey this year of some 100 mainland enterprises in the US found more than 90 per cent viewed “stalemate” in Sino-American political and cultural relations as a challenge of doing business stateside.

The report attributed the pessimism to a complex “policy environment and the hostile public sentiment influenced by ongoing US-China trade tensions”, advising mainland firms to appoint local employees with knowledge of the American culture and market.

As for TikTok, reports in May emerged that the social media platform boasting more than 1 billion monthly active users worldwide would lay off about 1,000 employees globally. The company last year disclosed it had 7,000 employees in the US alone.

TikTok had largely escaped vilification since 2020, when then-US president Donald Trump signed an executive order to ban it over national security reasons and asked parent company ByteDance to sell off its American operations.

Weeks later, then-TikTok CEO Kevin Mayer resigned just months into his job, citing pressure from the Trump administration.

Although a court later reversed the order, TikTok faced calls for a nationwide ban after the US Congress passed a law giving the company nine months to find a non-Chinese buyer or be removed from American app stores and servers.

Amid such developments, some executives at American subsidiaries of Chinese companies have reported encountering harassment.

Chuck Thelen, a North America-based vice-president for mainland battery maker Gotion High-Tech, said he has “personally experienced a great deal of bullying from a number of people”.

Thelen has been booed and yelled at during public meetings and is regularly accused of being “CCP-tied” despite Gotion anticipating its projects in Michigan and Illinois will generate more than 2,000 jobs.

US congressman John Moolenaar, a Michigan Republican who chairs the House select committee on China, has dug in.

“We must not welcome companies that are controlled by people who see us as the enemy and we should not allow them to build here,” Moolenaar said in July.

Billboards and yard signs telling Chinese companies they are unwelcome highlight the unease. At a Gotion job fair in Manteno, Illinois in January, a prospective employee told a local newspaper that, while “No Gotion” placards dotted the village, people still needed work to pay their bills.

In the current environment, Ha said uncertainty forced Western executives “to think twice about whether or not they are going to be able to commit and be successful”.

“Will this company be able to continue to operate? Will they be placed on the Entity List?” asked Ha, referring to the American government’s catalogue of trade restrictions.

Washington has added more than 100 Chinese companies to its blacklists since US President Joe Biden took office in 2021. The lists count about 600 mainland firms.

Pereira, a former Huawei Technologies employee, said “everyone wants to work at a place with long-term prospects” and seeing “the negative about your company will make you think twice about staying long term”.

For an American who has a bad experience at one Chinese company, it is “harder for you to decide to join the second”, added Pereira.

A report last September by Rhodium Group, a New York-based consultancy, found that “restrictive economic policies fuelling US-China economic decoupling over the past five years” had precipitated a “severe and prolonged” decline in not just mainland investment but also employment at Chinese companies in the US.

Unlike in 2017, when 229,000 Americans worked at Chinese firms, in 2022 only 140,000 Americans were employed by Chinese businesses, it said. In contrast, Germany hired 920,000 Americans and Japan hired 1,045,000.

Companies such as Midea have taken cues on localisation from successful counterparts in places like close US ally Japan.

“We don’t want to hide who we are,” said the Midea representative when asked about mainland firms trying to distance themselves from their origins.

“Midea learns more from Japanese and [South] Korean companies … where they don’t hide that they’re from Japan or [South] Korea. They also really do a great job of localising in America.”

Management’s approach can shape success, Pereira observed. “Many Chinese companies think if they hire a local person with a local face then that’s localisation.

“What you need to do is give the local staff autonomy to make real decisions, have control of the budget and let them run with their projects and make mistakes even and let them build their own teams,” he said.

“That’s a step that many Chinese companies have trouble with at this stage.”

Citing reviews on websites like Glassdoor, where former employees share feedback on employers, Pereira noted a common complaint was working overtime while getting free pizza on Fridays and nothing more.

“I’m not saying you have to pamper them like babies. But you do have to compare yourself to other local employers if you want to keep the best talent in the United States.”