The biggest puzzle in financial markets since Donald Trump won the US presidential election and his Republican Party gained control of Congress, limiting legislative curbs on the new president’s power when he takes office, is the sanguine reaction on the part of investors, especially in the United States.

Advertisement

While the prospect of tax cuts and deregulation is seen as a boon for stock markets, the threat of punitive tariffs reminiscent of the 1930s that spark a trade war should at least give investors pause for thought. One of the oft-cited reasons for the continued rise in the benchmark S&P 500 index is the persistence of American exceptionalism.

This is the notion that US assets, especially stocks, deserve to be valued more highly because of the US dollar’s role as the world’s pre-eminent reserve currency, the large US consumer market, the country’s vast energy resources and its dominance of the industries of the future.

The US is also exceptional in the closed nature of its economy. Merchandise trade as a proportion of economic output stood at just 19 per cent last year. In the euro zone, by contrast, the share was 75 per cent. The latter figure was more than twice the level in China, which can rely on its huge internal market.

However, more trade-dependent economies in Asia have much higher ratios. South Korea’s goods trade as a proportion of economic activity was 74 per cent, Vietnam’s was 158 per cent and Singapore’s was 179 per cent, according to World Bank data.

Advertisement

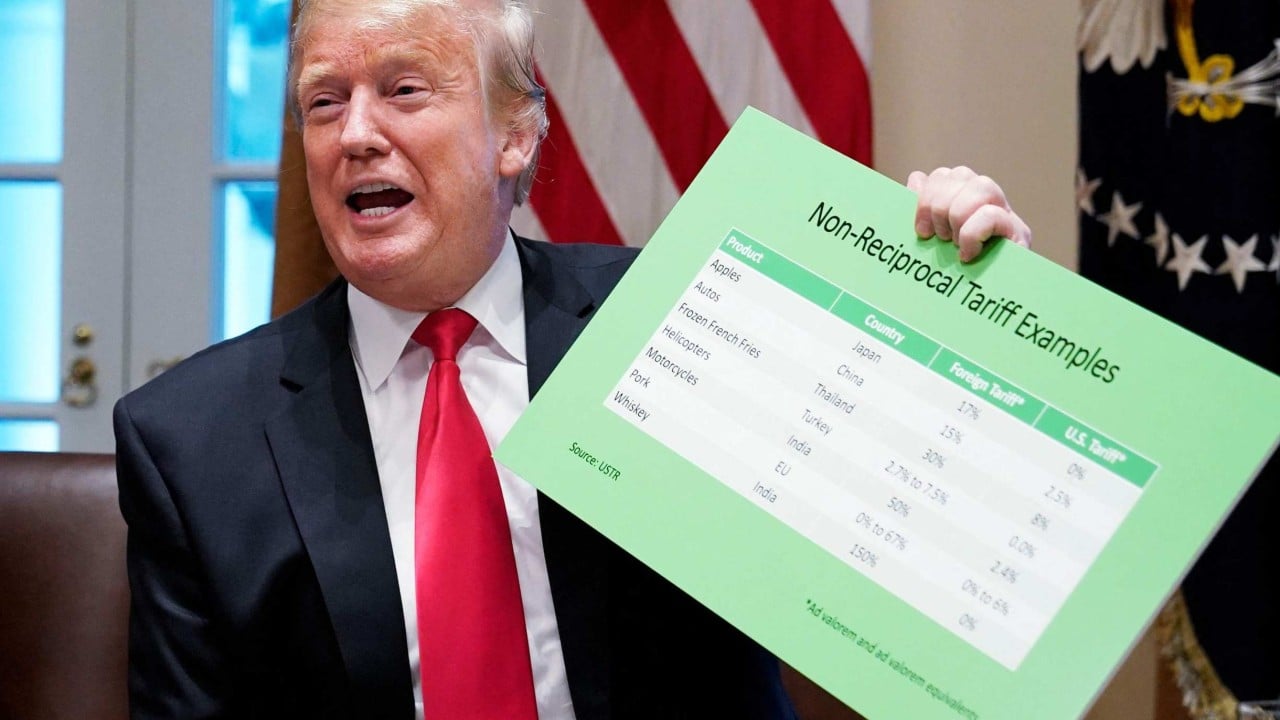

While the timing, scale and targeting of US tariffs under a second Trump administration are the subject of intense speculation, Asia is at the sharp end of the impending onslaught of protectionism.