China has “kicked” two of its experimental satellites into their designated lunar orbit, five months after they were left in limbo when the launch rocket’s upper stage did not fire.

The satellites, developed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, were shown operating in their planned distant retrograde orbit (DRO) in a PowerPoint slide attributed to CAS that started circulating on social media platform Weibo from Tuesday.

A researcher who works for CAS in Beijing and is familiar with the project confirmed to the South China Morning Post on Wednesday that the satellites DRO-A and B had been recovered.

The recovery was achieved by getting the spacecraft to fire their engines in a series of “perigee kicks” aimed at the closest point to the Earth, increasing velocity and extending their reach, the researcher said, on condition of anonymity.

The satellites left the Xichang launch centre on March 13 on top of a Long March 2C rocket but did not reach their destination, tens of thousands of kilometres above the moon’s surface.

The rocket’s first and second stages worked normally, but the Yuanzheng-1S upper stage did not, state news agency Xinhua reported the following day. “The satellites have not been inserted into their designated orbit, and work is under way to address this problem,” it said.

Two weeks later, the US Space Force tracked the pair at a raised orbit compared to the time of the incident, suggesting they were “still trying to get to the moon”, according to Harvard astronomer and space historian Jonathan McDowell.

At the same time, Scott Tilley, an amateur astronomer based in Canada, said the apparent orbital climb had probably cost considerable satellite propellant and would still not be enough to inject the satellites directly into a moon-bound trajectory.

Other challenges included limited fuel stocks and multiple transitions through the Van Allen radiation belt, where high-energy charged particles trapped in Earth’s magnetic field could damage the satellites’ electronics and solar panels, according to Tilley.

Since then, no further signs of the satellites were detected. “I bet the Space Force has lost it, as they are not good at tracking that far out,” McDowell said.

According to the slide, the satellites are in a large, circular orbit flying in the opposite direction to the moon’s rotation, giving them long-term stability and needing less fuel to maintain.

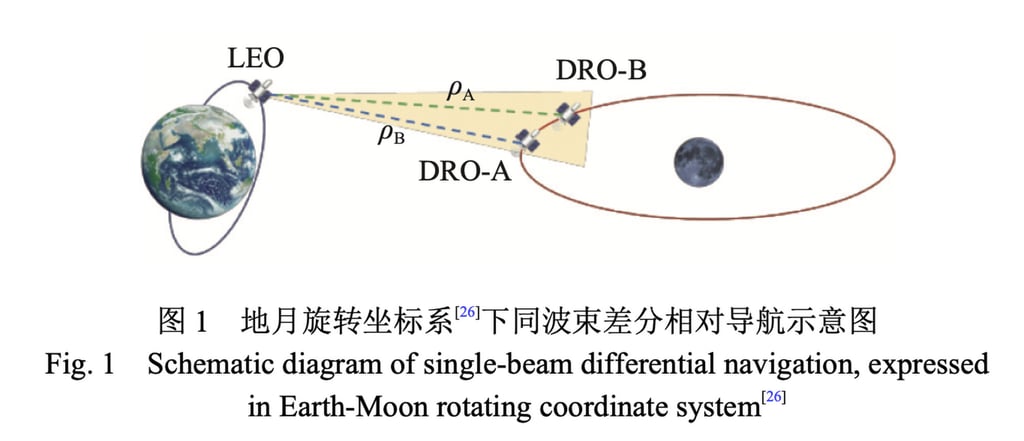

The slide’s information matches a paper published last year in the Journal of Deep Space Exploration, which said the satellites would be working with DRO-L – a third satellite that went into low Earth orbit in February.

The satellites are testing laser-based navigation and timing technologies between Earth and the moon, known as cislunar space.

CAS is also developing a next-generation constellation of satellites in a range of orbits near Earth, the moon and in between, for precision positioning, navigation and timing of future missions to the moon and beyond, the slide showed.