As candidates in Sri Lanka prepare for next month’s pivotal presidential election, analysts warn its future relations with India and China will hinge on the winner’s policies.

The race is on, with a diverse field of 39 candidates vying to lead the island nation out of its worst economic crisis in decades. It’s the country’s first presidential elections since the turmoil of 2022, which saw the once-dominant Rajapaksa political dynasty tumble from power amid mass protests and a crippling financial collapse.

Among the most closely watched contenders is Namal Rajapaksa, the 38-year-old scion of the former ruling clan. Representing the Sri Lanka People’s Front (SLPP), the son of popular wartime leader Mahinda Rajapaksa is seeking to restore his family’s legacy.

Other aspirants include incumbent President Ranil Wickremesinghe, contesting as an independent candidate instead of representing the United National Party (UNP) he has been associated with for close to five decades.

Sajith Premadasa, who split from the UNP in 2019, will represent Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), while Anura Kumara Dissanayake of National People’s Power (NPP), and leftist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) are also candidates.

The winner will decide the economic direction of the nation, which is currently in the process of implementing structural changes under a US$2.9 billion International Monetary Fund programme secured following 2022’s historic default.

Analysts say the outcome of the polls could shift the country’s delicate geopolitical balancing act between its two regional powerhouse neighbours – especially if the NPP’s Dissanayake wins a majority.

With recent political surprises in the region – including Narendra Modi losing a majority in parliamentary elections and strained relations between Delhi and Dhaka after the fall of Sheikh Hasina – “India is obviously going to look at this election with very, very sharp eyes,” said Uditha Devapriya, chief analyst at Factum, a Sri Lanka-based foreign policy think tank.

President Wickremesinghe is viewed as an astute diplomat for navigating delicate geopolitical currents. He has proven adept at maintaining amicable relations with nations in conflict, from hosting Iranian leaders to supporting US operations against the Houthis in the Red Sea.

Yet Wickremesinghe’s pro-India leanings are unmistakable. He has touted plans for currency integration with the Indian rupee and welcomed high-profile Indian investments, like those from the Adani conglomerate, which is thought to have close ties to Modi’s government. This has drawn vocal resistance from the opposition led by Premadasa.

“So obviously for the Indians, this [election] is going to be a game-changer,” Devapriya said. But whether it will truly upend Sri Lanka’s relations with China remains an open question. After all, it was Wickremesinghe himself who, as prime minister in 2017, gave the green light to the controversial 99-year lease of the Chinese-built Hambantota Port to a state-owned Chinese firm – a decision that drew fierce domestic backlash at the time.

Nilanthi Samaranayake, a visiting expert at the US Institute of Peace and adjunct fellow at the East-West Centre in Washington, said India would seek to preserve its positive ties with Sri Lanka, another vital neighbour in the region, especially given the challenges posed by a post-Hasina Bangladesh.

India has a long and complex history of working with both the incumbent Wickremesinghe and the previously dominant Rajapaksa clan. Yet amid this tangled web of relations, one thing is clear: whichever candidate emerges victorious, China will be eager to engage. The “bilateral relationship is entrenched”, Samaranayake said – Beijing has made deep inroads in Sri Lanka, and it’s unlikely to let a change in leadership disrupt its strategic foothold.

The potential rise of the NPP, however, has Delhi on edge. Its fiercely anti-India platform and its close ties to China are seen as a major thorn in the side for India, according to Harindra B Dassanayake, an analyst at Muragala Centre for Progressive Politics and Policy in Sri Lanka.

“India will be compelled to be cautious with a potential NPP leadership, while China will see it as an opportunity to increase their presence in the region,” he said.

Samaranayake echoed this sentiment, noting that the NPP would represent “a new and uncertain dynamic for India to manage in its external relations”.

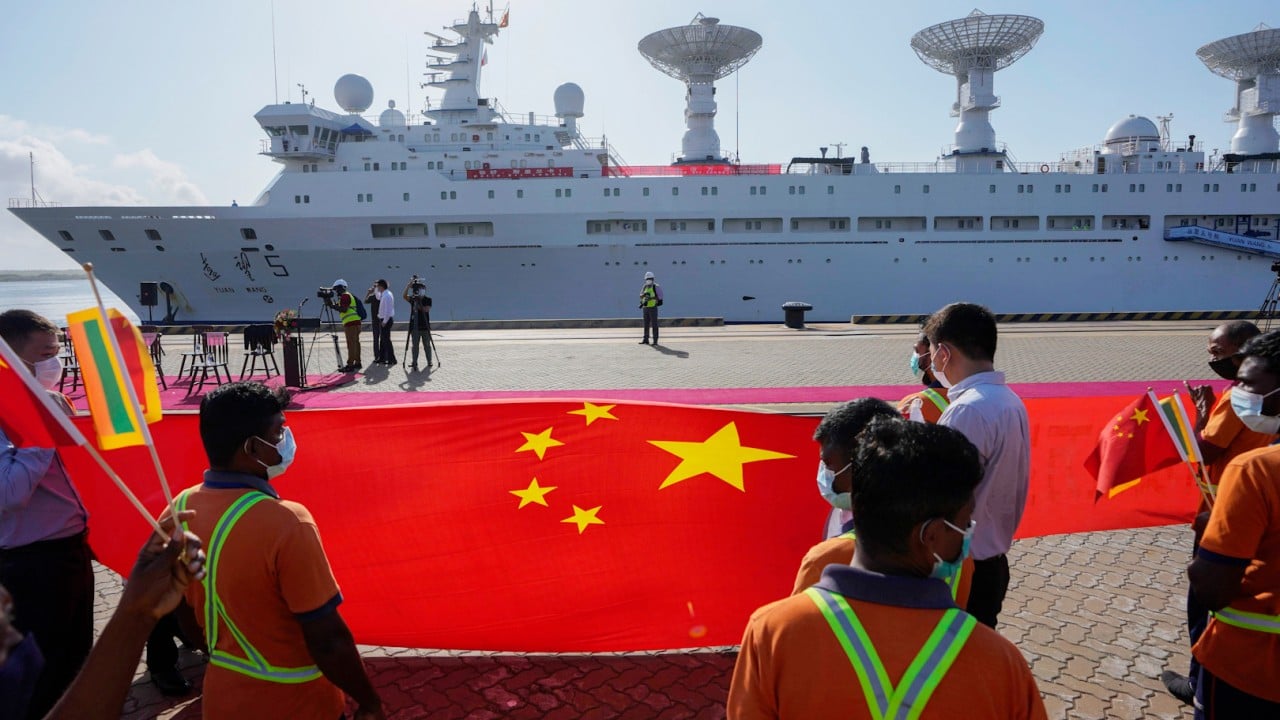

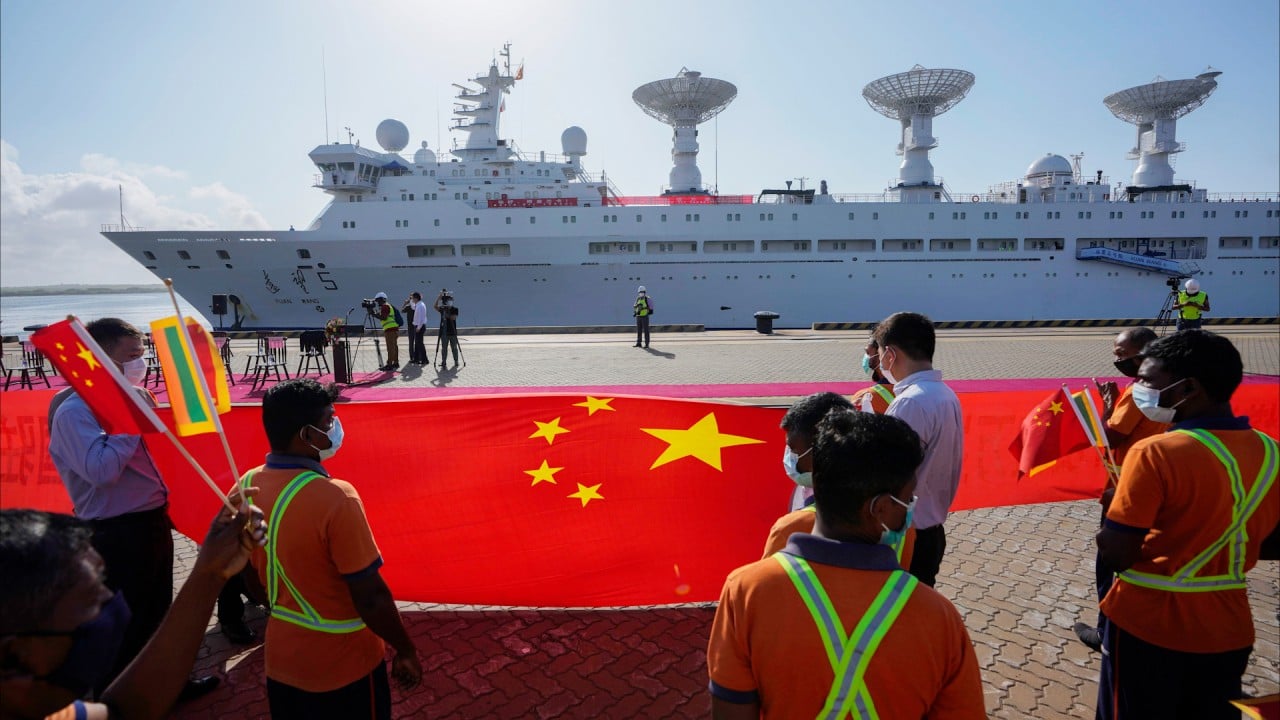

Sri Lanka has long prioritised its own domestic interests over the whims of its neighbours, but often pulls back if that means upsetting India’s regional threat perceptions, Samaranayake said – citing Colombo’s move to ban foreign research vessels from its ports amid Indian concerns over Chinese activities.

“This reflects the asymmetry of power for a smaller state, navigating the dominant country in its region,” she said. “If the NPP wins, this will be a new development in Sri Lanka’s history that observers will need to track for potential shifts in the country’s external approach.”

Meanwhile, a continuation of the status quo under either Wickremesinghe or Premadasa would likely mean business as usual for both China and India, Dassanayake said. However, he noted that the spectre of a “potentially weak political legitimacy” for the incoming president could “open a new avenue for increased pressure from geopolitical actors”.

Colombo has long viewed its foreign policy through an economic prism, rather than ideological allegiances, Devapriya said – though there is broad recognition that Sri Lanka now needs to be both “non-aligned” and “multi-aligned”.

“Multi-aligned in terms of trying to gain economic leverage by being as friendly as possible with everyone,” he said. “Non-aligned in terms of not being involved or privy to any of the big power plays and power conflicts and tensions that we are seeing right now.”