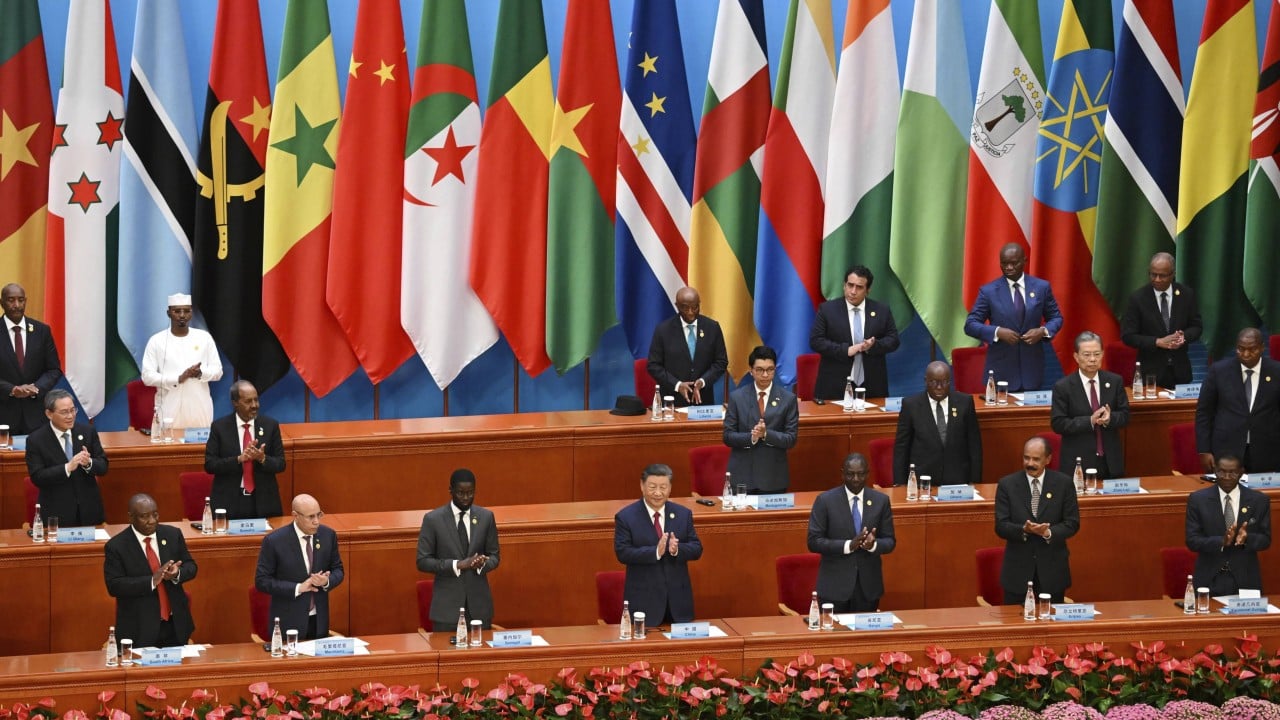

As Xi Jinping last week rolled out the red carpet in Beijing for more than 50 of Africa’s leaders, along with the UN’s Antonio Guterres, at the ninth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, one could only muse on the recent comment from Singapore’s Kishore Mahbubani that “the coming decades may belong to the Global South”.

Advertisement

Given its unlovely acronym, FOCAC, many can be forgiven for being unaware of this three-day “grand reunion of the China-Africa big family”. (Tiny eSwatini, population 1.2 million out of Africa’s 1.2 billion, sits alone outside the family because it has stubbornly maintained diplomatic relations with Taiwan since 1968).

After all, FOCAC only meets every three years – and the last reunion, hosted by Senegal, was necessarily a virtual affair because of Covid-19.

But you miss FOCAC’s significance at your peril – as with other creations like Brics, the Belt and Road Initiative, and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, all of them evidence of rising power and confidence among countries once dismissed as poor and benighted.

Such groupings, mostly driven by Beijing, have given form and substance to the once-vague concept of the Global South. They reflect accelerating change in the global balance of economic and diplomatic power. They illustrate vividly the persistent failure of the post-World War II powers, gathered around the Group of 7, to move beyond what many in the Global South see as a condescending, colonial relationship with the Third World.