“Where the hills and streams end and there seems no road beyond, amid shading willows and blooming flowers, another village appears.” This quote from the great poet Lu You describes a situation in which even though things look bad, events have actually taken a turn for the better. After years of reading negative news about Confucius Institutes, I feel that it’s quite fitting to apply this line to one of China’s other outreach efforts, Luban workshops.

Confucius Institutes are supposed to “tell China’s story well” by teaching Chinese language and culture as well as providing a space for cultural exchange. However, they have been subjected to intense criticism in Western countries for allegedly serving as propaganda tools and encroaching on academic freedom.

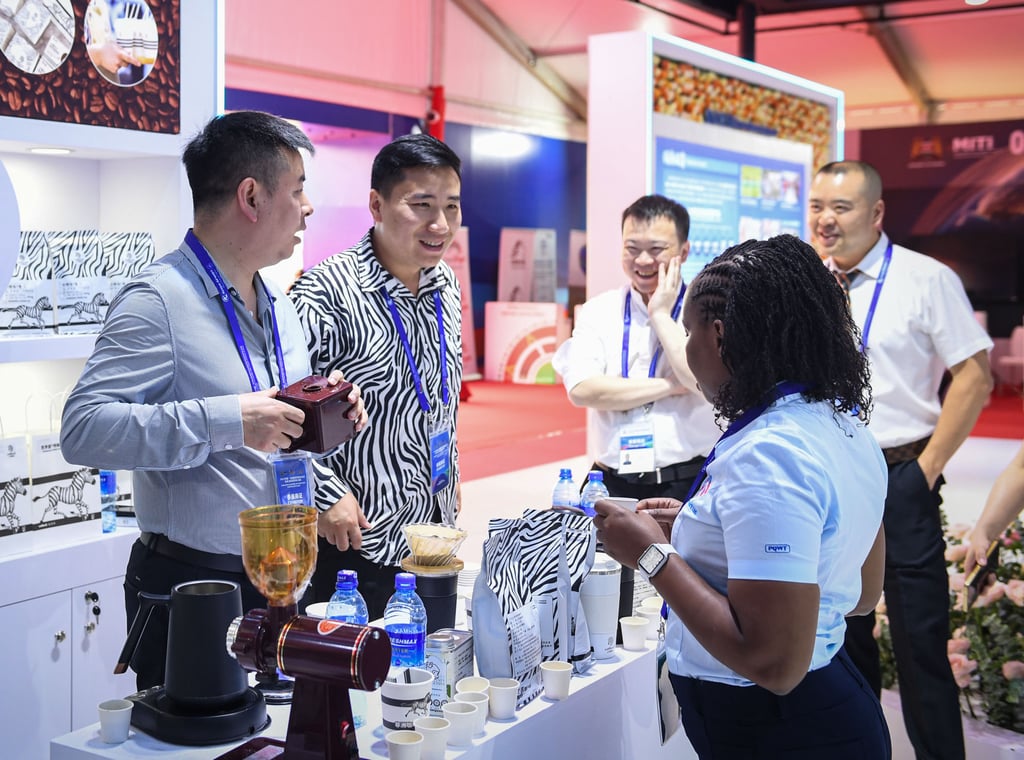

Fortunately, where Confucius Institutes have failed, Luban workshops have the potential to succeed. Since the first centre was established in 2016, the workshops have become a network of vocational training schools across Africa and Asia, offering courses such as electromechanics, new energy vehicles and “Internet of Things” engineering.

Another advantage of Luban workshops is that they’re geared towards the Global South as opposed to Western countries where China has met strong opposition and where many Confucius Institutes have been shut down.

Luban courses focus on skills that can be easily transferred to the workplace. This is arguably way more practical than courses offered by Confucius Institutes, such as calligraphy, which many would see as a hobby, or Chinese language, which requires years of study for students to only scratch the surface.

Thus, although they have a more technical orientation, courses offered by Luban workshops could have a stronger cultural impact than Confucius Institute offerings.

China struggled through years of decline and turmoil. It only began developing in earnest less than 50 years ago. Although still lagging behind in key areas, China has made huge strides in uplifting its people.

This story resonates with the Global South, where many countries have suffered exploitation for hundreds of years, and long for better economic conditions. Looking at China’s success, they know they too can succeed. This could explain the results of a recent poll published by Pew Research Centre last month, where 14 out of 17 middle-income countries had a favourable view of China.

When students at Luban workshops learn how to operate Chinese equipment, they are not only learning practical skills but also indirectly learning about China. It’s a form of education outreach that tells a pretty good China story.

However, for all the improvements that Luban workshops have made over Confucius Institutes, they still appear to be a one-way bridge – a flow of expertise from China to the Global South. For example, the Chinese Ministry of Education says these training centres bring the “standards, models, equipment and programmes of Chinese vocational education” to the countries involved.

Zhao Zhiqun, a vocational education specialist at Beijing Normal University, believes that “in the future, the focus of China’s vocational education should be about serving Chinese enterprises going abroad, by cultivating local vocational talent teams that understand Chinese language and culture”.

Such attitudes inadvertently leave an impression of condescension. It would be better if Luban workshops also facilitated the flow of information from the Global South to China, doing what Matteo Ricci did in the 16th C, only without the religious aspect.

Ricci was a well-educated Renaissance man. He helped bring Western scientific developments to China, such as those in astronomy, mathematics and geography. His “Great Map of Ten Thousand Countries” awed the Chinese. He was also one of the earliest Western scholars to read Chinese literature and study Chinese classics.

His Latin translation of the Chinese classics, The Four Books, as well as his letters and memoirs on his impressions and experiences in China, provided Europeans with fundamental knowledge about Chinese culture. He was a true cultural bridge between the East and the West.

Since Luban workshops already aim to bring technological advancements to the Global South, the next step should be to introduce the Global South to Chinese audiences.

Indeed, the term “Global South” itself is a vague concept. I bet most Chinese people are like me, and only have a fuzzy idea of what it means. We probably know more about American politics than the differences between Ethiopia and Kenya.

This is where Luban workshops could make a difference. Like Ricci, Luban workshops could use their geographical advantage to become a true cultural bridge between China and the Global South.

April Zhang is the founder of MSL Master and the author of the Mandarin Express textbook series and the Chinese Reading and Writing textbook series