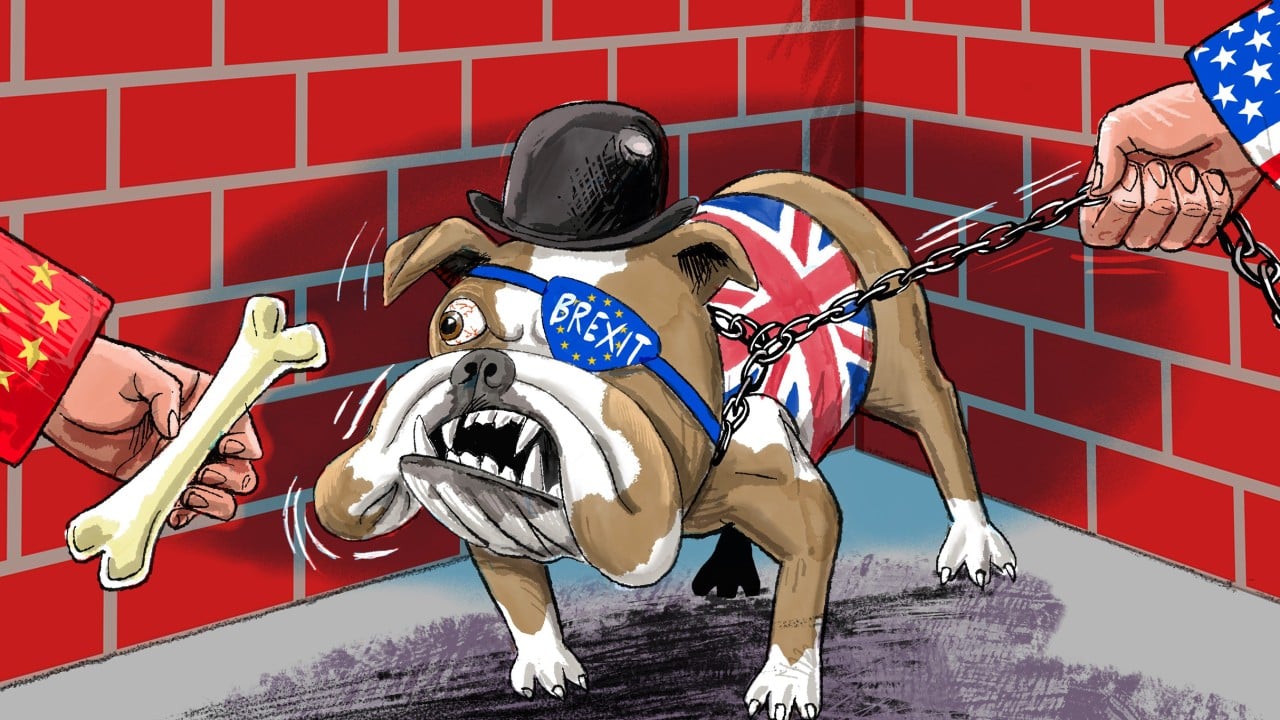

British politics is once again allowing domestic drama to override strategic thinking. The latest hysteria surrounding alleged Chinese spying and Beijing’s plans for a new embassy in London illustrates how Britain’s foreign policy risks being driven less by sober calculation than by political theatre. The consequences could be severe: Britain is edging towards repeating the mistakes of Brexit, trading its long-term national interests for short-term populist gain.

Advertisement

In the United States, the turbulence of Donald Trump’s presidency is reshaping the global order, disrupting trade, tariffs and even long-standing alliances. For Britain, logic suggests keeping a strategic distance, preserving room to manoeuvre and cultivating a wider range of partnerships.

Instead, the British political climate is making such a balance nearly impossible. Critics of Britain’s engagement with China are so quick to frame any cooperation as dangerous that London risks being left with only one option: to rely on Washington and align almost automatically with American positions. This deference is strikingly asymmetric. When Trump imposed sweeping tariffs that disrupted global supply chains, Westminster did not erupt with the outrage we now see over China.

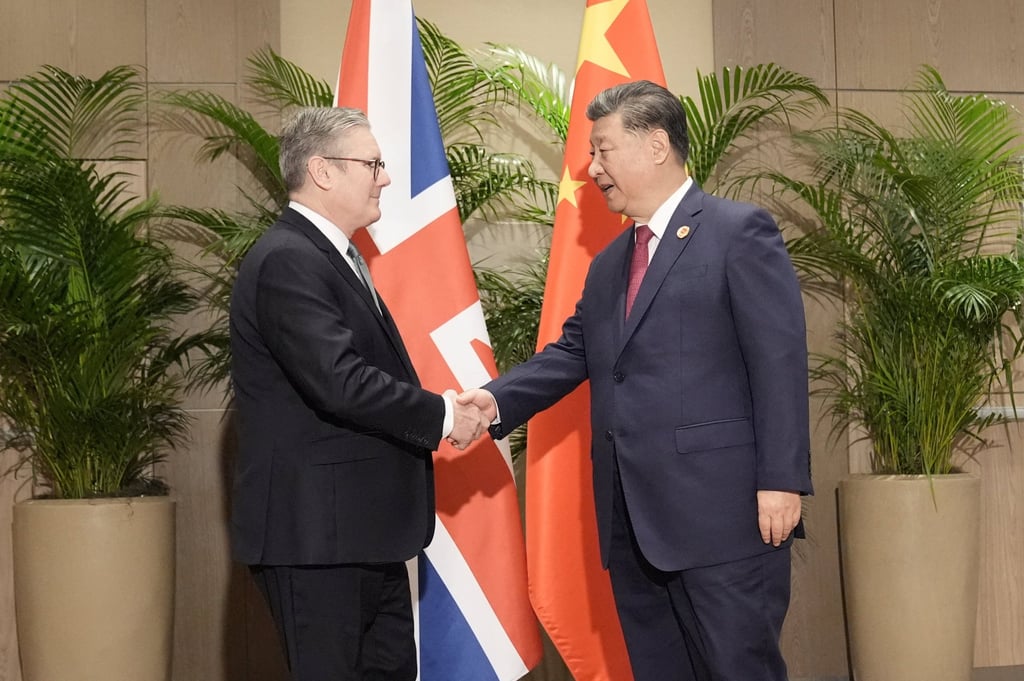

Yet today, a single weak spy case is enough to trigger headlines about a full-blown scandal, calling for the prime minister’s resignation. The controversy has become entangled with Beijing’s proposed new embassy in London – an issue that should never have been linked in the first place – leaving even less room for serious diplomacy. Any statement from China is reflexively cast as a threat from an authoritarian regime, while any attempt at dialogue is dismissed as weakness.

This pattern is painfully familiar. Brexit – Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union – was justified with passion, slogans and sentiment, but little coherent strategy. Years later, it is clear the economic and diplomatic costs were badly underestimated. Britain is poorer, more isolated and still without a credible plan to replace what it lost.

Advertisement

Now, the issue with China risks becoming the next Brexit. A rupture with the world’s second-largest economy would be driven not by a measured strategy but by political reflex. The result would be further self-inflicted isolation just when Britain can least afford it.