The issue of foreign judges serving, or ceasing to, on our Court of Final Appeal has flared up, raising important questions about Hong Kong’s future. There has been a flurry of commentaries, some heated, not all of which have helped clarify matters.

To set the scene, let us start with the Basic Law. Article 8 provides that “laws previously in force in Hong Kong”, including “the common law”, “shall be maintained”. President Xi Jinping, visiting Hong Kong in 2022 for the 25th anniversary of the handover, reinforced the commitment in his July 1 speech. He twice mentioned the common law as continuing to apply in Hong Kong.

The question of foreigners serving in our judiciary is covered in two places in the Basic Law. Article 92 says that “judges and other members of the judiciary […] may be recruited from other common law jurisdictions”. Article 82 provides that Hong Kong “may as required invite judges from other common law jurisdictions to sit on the Court of Final Appeal”.

And earlier this month, a senior mainland official affirmed that “foreign friends” were welcome to remain part of Hong Kong’s legal system. Nong Rong, deputy head of the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, in a speech delivered in English, told a conference that Hong Kong’s legal practitioners, including foreigners, supported the rule of law. Clearly, the central government fully supports Hong Kong’s common law system.

In summary, the rule of law, common law and foreign judges are all here to stay.

In the last few years, there have been a number of withdrawals from the list of foreign judges invited to sit on the Court of Final Appeal, by way of resignation or non-renewal of contract. These events have led some to query whether the arrangement is still in Hong Kong’s best interests.

One Post commentary suggested the time for the arrangement had passed because Hong Kong’s legal system could include mainland talent and incorporate some mainland legal practices. I disagree. Such a sentiment plays into the hands of detractors looking for every opportunity to say we are becoming just another Chinese city. The rule of law and common law system are precisely what distinguishes us, and makes us more useful to the country.

More reasonably, Executive Council member Ronny Tong Ka-wah has asked whether we have not now built up a sufficiently large and respected body of common law practitioners that we can dispense with outsiders. It is a legitimate question and in theory, the answer must be yes. But that is to ignore the optics of the situation, the perception in the minds of the international business community.

Twenty years ago when InvestHK was just starting out and we talked about the advantages of doing business here, what often clinched the argument was the presence of foreign judges, including on the Court of Final Appeal.

The annual surveys of foreign and mainland businesses in Hong Kong seeking views on the city’s attractiveness invariably rank the rule of law, independent judiciary and common law system as key factors. Why would we give up what makes us the best?

The issue has become heavily politicised, particularly since the “Five Eyes” nations – the United States, Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand – have chosen to see China as a threat.

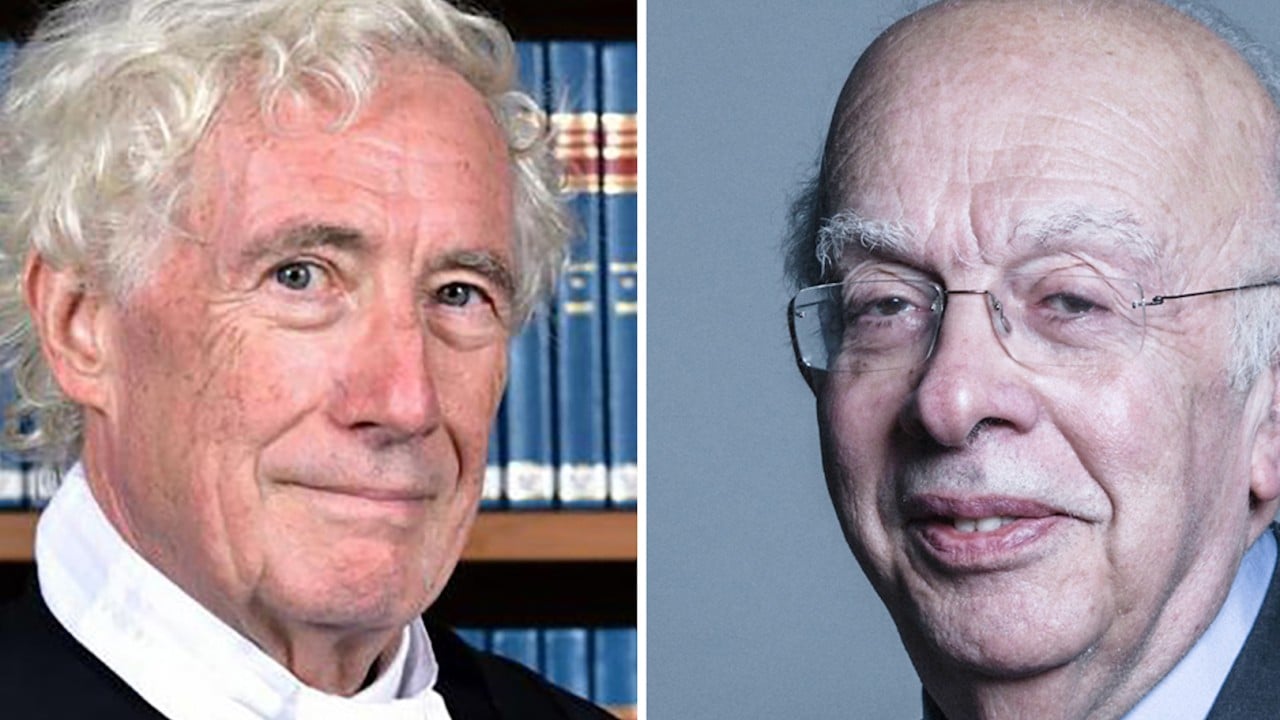

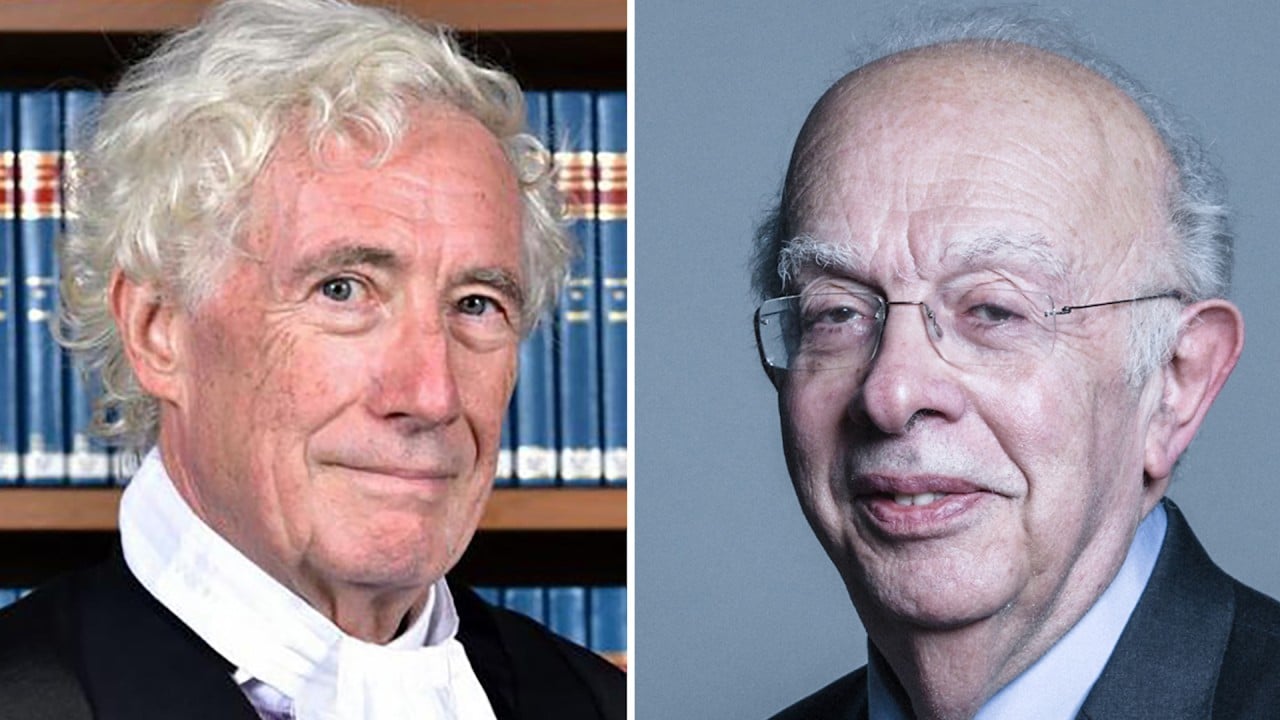

After Beijing promulgated the national security law for Hong Kong in 2020, there were calls in the UK for British judges to withdraw. In 2022, two serving British Supreme Court judges – Robert Reed and Patrick Hodge – did so in a high-profile way. It is widely believed they did so on British government direction, though this has been denied.

Earlier this month, two more British judges stood down. One, Lawrence Collins, expressed continued confidence in the judiciary here while the other, Jonathan Sumption, gave his reasons in a Financial Times commentary, saying the rule of law here was in grave danger.

Meanwhile, former Canadian chief justice Beverley McLachlin, aged 80, gave notice she would not be renewing her term when it expires.

Western media have used the withdrawal of foreign judges as evidence of Hong Kong’s decline, supporting the false narrative that Hong Kong is over.

Nonetheless, it would be wrong to claim there has been no change of mood or atmosphere in Hong Kong in recent years. Some public statements have taken on “wolf warrior” tones.

Perhaps the most egregious example of undesirable administrative behaviour is the abuse of the police bail system under which many young people not yet charged with, let alone convicted of, any offence have been kept in limbo, in some cases for many years. A mature, confident government would not behave like this, or pretend it did not know the scale of the situation.

Specifically on the matter of the Court of Final Appeal’s foreign judges, what are we doing to keep those we have and replenish the supply of willing ones?

The “Five Eyes” governments seem determined to browbeat their citizens into withdrawing, but are there any countermeasures we can introduce to bolster the morale of those who remain and inspire new ones to come and see for themselves?

Are there no alternative jurisdictions we could draw on? Both Ireland and India practice common law and both countries are familiar with and have a history of resisting British bullying.

If the presence of foreign judges in our courts is one of the distinguishing features that makes Hong Kong different and special, then we should be doing everything we can to preserve that difference.

Mike Rowse is an independent commentator