President-elect Donald Trump has vowed to issue a day-one executive order to restore federal approvals for the proposed Keystone XL Pipeline, similar to his January 2017 directive overturning the Obama administration’s 2015 rejection of the same project.

Trump’s first-term Keystone restoration was reversed by President Joe Biden in a January 2021 executive order, again halting development of the 1,180-mile pipeline between Alberta, Canada, and Steele City, Nebraska.

While Trump 2.0 could nullify Biden’s directive in a pen stroke on Jan. 20, 2025, he won’t be able to resurrect Keystone XL because the project no longer exists.

“My understanding is the company has pulled the steel out of the ground and shipped it elsewhere and found alternative routes to get its product to market,” said Brett Hartl, government affairs director for the Center for Biological Diversity.

“That would make it hard for Trump to approve an application that doesn’t exist,” he told The Epoch Times.

“Like most black-and-white stories, it’s a bit more complicated than that,” senior market analyst Phil Flynn with Chicago-based Price Futures Group told The Epoch Times.

But a simple straight line between supply and demand illustrates why XL was—and is—needed, he said.

“Whether or not this pipeline gets built, there will be another pipeline along the same route, just it’s not called ‘Keystone,’” Flynn said.

Toronto commodity analyst Rory Johnston, founder of CommodityContext.com, said a lot of things had changed since 2021 when “they had all the pipes in place in many places, like on-site, waiting to be installed.”

“Now it’s a zombie pipeline. What is dead can never die,” he told The Epoch Times.

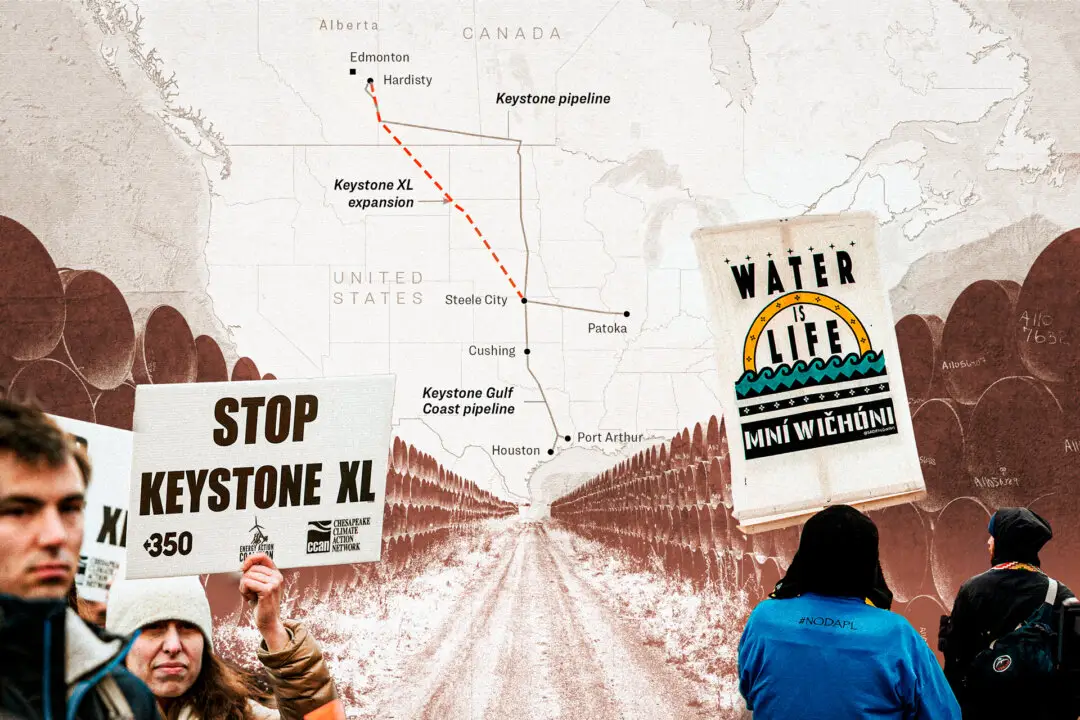

Calgary-based TC Energy’s Keystone XL Pipeline 2008 proposal sought to add a 30-inch diameter line traversing 1,179 miles from Hardisty, Alberta, to Steele City, Nebraska, to its existing 3,000-mile Keystone pipeline network.

The XL pipeline would add 800,000 barrels per day (bpd) to TC Energy’s existing Keystone network, including up to 730,000 bpd of tar sand crude oil from Canada and 100,000 bpd from North Dakota’s Bakken Formation.

Crossing the border at Morgan, Montana, XL would run 875 miles to Steele City, where it would split, sending oil east to an Illinois refinery and south to Cushing, Oklahoma, a trans-shipment hub with 90 million barrels of storage space and access to its Marketlink common-carrier pipeline, which is linked to Texas refiners.

The proposed pipeline drew heated opposition from an array of groups, including environmental nonprofits, climate change lobbyists, Native American organizations, land owners, and local governments, particularly in Nebraska.

Although preliminary approvals were secured by 2014, President Barack Obama in 2015 vetoed XL as unnecessary for the nation’s energy security, locking it in limbo.

Following his Jan. 20, 2017, inauguration, Trump restored XL’s approvals. Four years to the day later, Biden revoked Trump’s restoration.

After failing to regain momentum during Trump’s short-lived reprieve and facing at least four years of assured Biden sanctions, TC Energy withdrew its application in June 2021.

In July 2021, TC Energy filed a $15 million claim against the U.S. government for Biden’s “unfair and inequitable” revocation of its XL permit, claiming the 13-year “regulatory rollercoaster” caused significant financial harm.

“TC Energy, they did everything right and had spent a whole bunch of money, had it approved, and they pulled the rug from under them,” said Flynn, who also produces The Energy Report.

In October 2024, TC Energy announced it will “spin off” its pipeline business to a subsidiary, South Bow. Since then, portions of the pipeline have been dug up and sold, easements have lapsed or been transferred, and investors have shied away.

In November, water company Cadiz bought 180 miles of steel originally purchased for the pipeline to transport water through the Mojave Desert.

Some speculate Trump’s Dec. 10 pledge to expedite permitting and trim environmental reviews for projects worth at least $1 billion could spur interest in reviving XL.

South Bow “is noncommittal,” Flynn said, noting he’s curious if Trump’s fast-track pledge could spur Keystone’s exhumation.

“When you have the power of the presidency behind you, that might entice them,” he said. “I think this could be fast-tracked. If South Bow wants to do this, it could entice them to do it.”

South Bow isn’t saying much one way or another.

“South Bow supports efforts to transport more Canadian crude oil to meet U.S. demand,” South Bow spokesperson Solomiya Lyaskovska said in an emailed response to The Epoch Times’ queries. “South Bow’s long-term strategy is to safely and efficiently grow our business.”

Shifting Landscape

TC Energy’s primary reason for building XL was to boost its capacity to ship Alberta tar sands crude to refineries and shipping terminals for export.

In May 2023, Trans Mountain Pipeline completed the expansion of its existing 610-mile TransMountain Pipeline between Edmonton and Burnaby, British Columbia, from 300,000 bpd to 890,000 bpd capacity.

The expanded pipeline gave Canadian exporters the port access they needed, defusing the urgency for XL, but the Gulf is still the prized destination, Flynn said.

Canadian producers “love access to the Gulf. That’s where all the refineries are and where the ships are already geared to export everywhere in the world,” he said.

Many say market conditions indicate there’s no need for another cross-border oil pipeline. U.S. production is at an all-time high, and Canada is exporting at record levels. OPEC has at least 5 million bpd of spare capacity.

Meanwhile, economic forecasters mostly project growth in global oil demand will slow, making investors wary of long-term infrastructure commitments.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) projects demand for oil will increase between 0.9 percent and 1.3 percent annually the next few years, below pre-2020 annual averages of 1.5 percent growth. In October, it lowered its 2025 world oil demand by 20,000 bpd.

“Declining demand … is central” to opponents’ arguments, Hartl said.

“The reality with drilling is it’s always contingent on price points, on profitability,” he said. “The company would have to want it, to commit resources to drill and, right now, there’s little motivation. The market itself doesn’t bear it.”

Shrinking Market

This gradual demand downturn has a subsidiary influence across related industries. According to a 2024 IBISWorld analysis, for instance, the U.S. pipeline construction industry includes 1,870 businesses and 184,000 workers and annually generates $47 billion in revenues. However, those revenues have been declining an average of 7 percent each year since 2019.

Johnston said such forecasts temper investment, noting that the project still languished, even after Trump approved XL.

“They had four years, and over those four years, [TC Energy] barely got 10 percent of the pipeline constructed,” he said.

The “weird inherent tension in trying to drive [energy prices] down but keep it profitable” is unsustainable, Hartl said.

The growth in oil consumption has declined for about 15 years and will continue to slow, Texas Tech University Department of Economics Professor Michael Noel told The Epoch Times.

“All of that is true,” he said, buttressing XL opponents’ arguments.

“So, the argument is we won’t need this infrastructure, so we’re going to put up with higher prices now because we’ll get lower prices later,” Noel said. “That’s great, but that argument historically means that you’re going to end up with higher and higher and higher prices while you keep on waiting for the lower thing to come.”

The “better idea” is “always build the infrastructure you need when you need it, then you’ll have cheaper prices now, and then at some point when you don’t need it, it gets decommissioned,” he said.

Even if renewable energies power the grid, “it takes time to build these things,” Noel said. “So the question is, what do you do in the meantime?”

Political Challenges

Environmentalists spearheaded opposition to XL. They argued that developing fossil fuel infrastructure would contribute to climate change by enabling the consumption of oil sands, a heavy, carbon-intensive crude.

The 3-million-member National Resource Defense Council (NRDC) noted that Canada tar sands oil is a viscous sludge that leaves hazardous byproducts and releases substantial carbon emissions.

“Making it usable creates three to four times the carbon pollution of conventional crude extraction and processing,” NRDC’s analysis states.

The Center for Biological Diversity, which sued the Trump administration more than 266 times, is “prepared to push back on things that are clearly illegal” with Trump set “to be more aggressive with executive power,” Hartl said, but it does not anticipate another legal fight over XL.

“At the moment, there isn’t a big marquee pipeline project” on the books, he said.

The Northern Plains Resource Council, a Montana-based coalition that galvanized local landowners and tribal governments, is “in a wait-and-see mode,” said a representative who spoke anonymously on background

“To be fair, there were [legitimate] arguments” against the pipeline, Noel said, but most were ideological and “had nothing to do with where the pipeline was. It was just that the pipeline existed, and it’s the same argument for every pipeline—that pipelines exist, that oil exists.”

Flynn had the same logic.

“Nobody stopped to think how [pipelines are] the safest, most environmentally sensitive way to move oil,” he said. “Nobody stopped to think how it would not significantly add to carbon emissions because the oil was going to be produced anyway.”

Symbolic or Shovel-Ready?

For Trump, restoring XL is “not literally” about one pipeline but about supporting “pipeline infrastructure,” Johnston said.

He said re-permitting XL would fit within Trump’s “drill baby drill” campaign pledge to deregulate energy, generate more power, and increase production to lower electricity and fuel costs.

Hartl said Trump’s pledged post-mortem approval for XL “really is code” for deregulation, environmental rollbacks, and streamlined permitting.

“I’ll be constantly hitting refresh on the White House webpage” after Trump’s inauguration, he said.

Noel said such policy commitments must be encoded into legislation by Congress rather than issued by one administration in executive orders that its successor administration will rescind.

“If you got the green light to go ahead and start this thing all over again, there’s a very good chance in four years, on the first day of the new Democratic administration, it gets killed again,” he said.

Yet, as Trump’s Energy Secretary-select Chris Wright recently told Barrons, resurrecting XL may be more feasible than some realize.

“It’s already been through an exhaustive environmental review,” Wright said. “Canada is probably the second-biggest country that could grow its oil and natural gas production. It’s just limited by access to markets. Build that pipeline, restore some confidence in Canada, and in the U.S. industry.”

With a fast-track incentive for $1 billion projects, Flynn said it would “be tougher for [opponents] to slow things down with Trump in office” and Republicans in control of both chambers.

True, Hartl said, but only if the next GOP majority isn’t as dysfunctionally factional as its current lame-duck iteration.

When Trump was sworn in for his first term in January 2017, Republicans had a 241–194 House advantage. He’ll begin his second term with the GOP holding a 217–215 chamber toehold riven by factions.

“I’m a little puzzled how they expect to accomplish things when they can only afford one or two defectors in any particular vote,” Hartl said. “I’m certainly going to have the popcorn out.”