Regardless of who wins the election, the next president likely will have to deal with an economic slowdown next year, several experts told The Epoch Times. The government may try to intervene, but there’s a risk any remedies will cause harm, they said.

On paper, the U.S. economy is chugging along nicely. Unemployment is low, the markets are up, and the gross domestic product (GDP) came in 3 percent above inflation in the second quarter. Third-quarter GDP is expected to climb 2.6 percent above inflation, and median wages increased by nearly 2.5 percent (adjusted for inflation) over the past two years.

Yet, a large proportion of Americans don’t feel like the economy is working well for them.

Only about 21 percent consider business conditions “good”—a far cry from the nearly 40 percent who thought so five years ago, according to Consumer Confidence Index surveys. Self-reported family financial situation has virtually stagnated for the past year, the survey shows. Meanwhile, credit card debt is up about 16 percent over the past two years.

Economic indicators likely won’t remain as encouraging for long, said Lance Roberts, the chief investment strategist at RIA Advisors.

“I think you’re going to start looking at much lower rates of economic growth somewhere sub-2 percent growth as consumers become challenged by making ends meet,” he said.

Financial markets should brace for a similar slowdown, according to Adam Taggart, founder of Thoughtful Money, a financial education firm.

In recent weeks, Taggart spoke to more than a dozen market analysts and noticed there’s an unusually wide disagreement on the market direction.

His best suggestion is to follow the global liquidity model produced by Michael Howell, chief executive of CrossBorder Capital, a London-based market research firm.

The model indicates that bull and bear markets in today’s economy trace liquidity: how much money is in the system overall. Howell posits that liquidity waxes and vanes in cycles. Right now, he says the market is in an upward cycle that’s likely to peak next year, signaling a slowdown.

“Just like when you throw a ball up in the air as it gets close to its apex, its speed of rise is declining,” Taggart said.

Market predictions, however, assume that “everything remains status quo next year,” Roberts noted.

As the economy slows down, letting a large numbers of Americans descend into poverty would be politically indigestible for whomever becomes the president. It would be expected for the administration to intervene, he suggested.

“The system will do everything it can to fight it,” Taggart said.

How that may happen would partly depend on who wins.

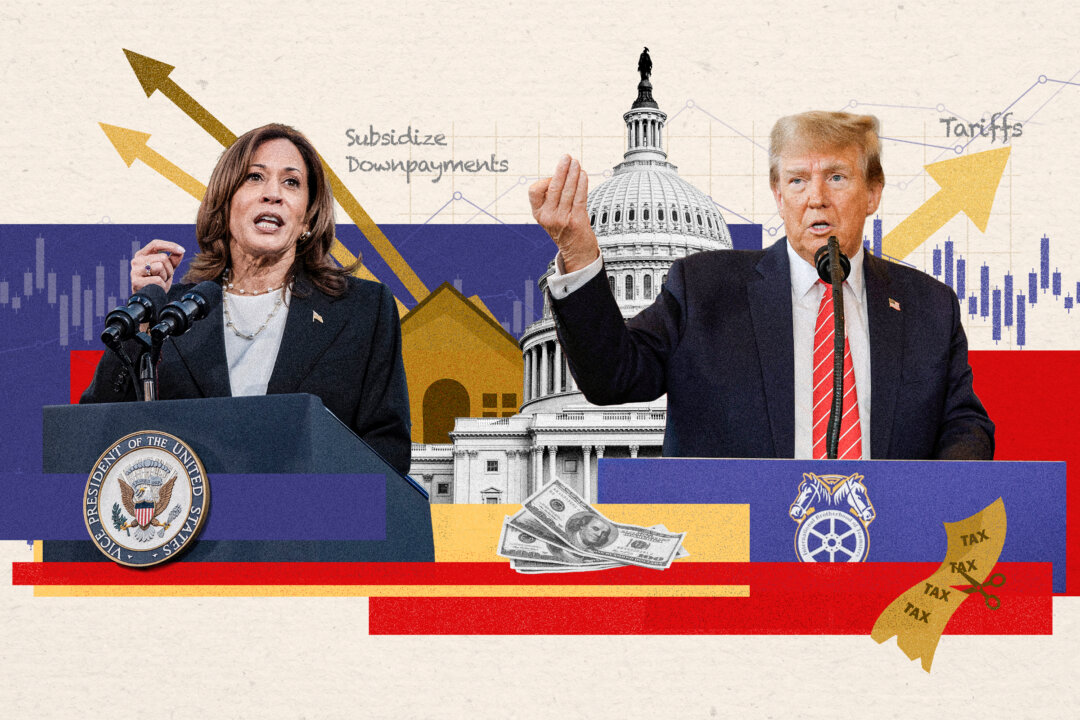

If Vice President Kamala Harris is elected and gets Congress on her side, her plan would be to institute a series of government programs, such as to finance public housing and subsidize downpayments for first-home buyers.

“That’s very inflationary,” Roberts said.

The programs would be at least partly financed through increased taxes on higher earners, which could offset the impact on government deficit. But that’s not the main issue, as Roberts explained.

“Once you start providing capital to people to go buy stuff, that massively increases the demand on the available supply,” he said.

Housing construction can’t be increased at will due to limited number of people skilled to build them.

“You’re trying to solve a housing problem; you’re going to massively create one at that point,” Roberts said.

“If we give $25,000 to three million people to go buy houses, there’s not enough houses to buy, and they can’t build them that fast. So that’s going to be very inflationary.”

Not only would housing prices rise but also construction labor, commodities, and transportation, which all are tied to the housing supply chain, Roberts said.

If former President Donald Trump wins and gets Congress on his side, his plan would be to cut taxes, increase domestic energy production, cut regulations, and impose tariffs on imports.

Cutting taxes and regulations stimulates economy, as does cheaper energy. Tariffs, on the other hand, could create problems, Roberts said.

Even if the tariffs are calibrated to minimize impact on domestic prices, they would “put pressure on foreign trading partners,” he said.

“It’s certainly going to ramp up a lot of the rhetoric in the market … That’s going to make the markets nervous at that point, depending on how aggressive these tariffs are.”

That has real economic impact as nervous investors are more hesitant to invest.

He also suggested Trump would press the Federal Reserve to “cut rates more aggressively.”

“The Fed’s not going to respond to that, but it’s going to give a lot of rhetoric to the markets,” he said.

“So you potentially get an environment next year where you get a bit stronger growth, but a lot more volatility—both in markets as well as the economic data.”

Split Congress Scenario

It could easily happen that whichever candidate wins, she or he won’t get majority in both chambers of Congress. In that case, the Congress would likely remain gridlocked, with neither party getting its way. Government spending would stay in an autopilot mode of about 8 percent annual increases, Roberts said.

“That’s the best outcome for the markets. It’s probably the best outcome for the economy, because nothing actually happens that causes a potential unexpected shock to markets.”

The Federal Reserve is expected to continue to cut interest rates, perhaps down to about 2.5 percent. To shore up prices of Treasury bonds, the Fed would likely start buying them again, switching from quantitative tightening to quantitative easing, Roberts predicted.

Economic Shock

Another scenario could involve an unexpected shock to the economy, such as a war disrupting global trade, another pandemic, or other black swan event.

Since 2008, the government and the Fed have established a toolkit for managing economic downturns that sacrifices long-term prosperity for immediate stability, Roberts said. That includes slashing interest rates to zero, injecting money into the financial system through buying up Treasuries and other assets, and giving money directly to the people, such as through the pandemic “stimulus checks.”

“That will be the game plan, because it worked last time,” he said.

Taggart agreed.

“All of that stuff very well may be on the table, but before we get to that stage, we’re going to have to go through the pain of the system starting to falter, which then triggers the central planners’ response,” he said.

It appears, however, that every time the government and the Fed scrambles to salvage the market and economy in a time of crisis, the required intervention becomes much larger.

Next time, “it would probably happen on a scale that we can’t imagine right now,” Taggart said.

Such interventions would most likely restart inflation, both he and Roberts acknowledged.

“The thing that always has to pay the price of intervention is purchasing power of the currency,” said Taggart.

Inflation or Bust

Some analysts believe that another bout of high inflation is not only inevitable but possibly the only way out.

Much of that attitude centers around the issue of “fiscal dominance.”

The term suggests that the Fed, despite describing itself as independent of the government, is still ultimately beholden to the continuous functioning of the government. While the official mandate of the Fed is to keep unemployment low and inflation around 2 percent, all those concerns are in reality superseded by the necessity of keeping the government able to borrow more money.

“It just has to keep the credit markets continuing to flow and the debt serviceable,” Taggart said.

By raising rates to counter inflation in 2022–23, the Fed made it increasingly expensive for the government to borrow, to the point that debt interest has superseded military expenditures.

Market researcher Luke Gromen recently told Taggart that the Fed’s recent half-precent rate cut signaled the central bank is aware that the rates have been too high to be fiscally sustainable.

Gromen pointed out that debt interest plus entitlement programs, such as Social Security and Medicare, currently consume the bulk of government tax receipts. If the budget gets even more off balance, the Treasury may start to have real trouble finding buyers for its debt.

“Once you’re over tax receipts, the bond market’s going to see right through that,” he said.

In the absence of substantial spending cuts, which could plunge the economy into a recession, the other option is to cut rates, let inflation rise again, and thus reduce the debt as a share of the inflated GDP.

To ensure that long-term Treasurys remain in demand, even when they yield less than inflation, Gromen speculated the government may at some point institute capital controls, such as by requiring funds to hold certain percentage of their portfolio in long-term treasuries.

One wild card that may mix up the economic outlook is technology, especially improvements in automation powered by artificial intelligence (AI). Depending on “how quickly AI is going to show up and how quickly robotics are going to show up,” productivity could significantly increase and help offset inflation, Gromen said.