A key US-China science and technology treaty has expired with little apparent evidence of progress following a year of delay fuelled by American apprehensions over how China has benefited from the decades-old pact.

Renewal of the US-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA), the first bilateral deal signed between the two countries in 1979, had been postponed twice since August 2023. The most recent six-month extension expired on Tuesday.

A State Department official on Thursday said on background: “I don’t have anything additional to share at this time.”

This followed word by the same official a day earlier that the two sides were “in communication” about the STA “including on the necessary guardrails around any such cooperation, strengthened provisions for transparency and scientific-data reciprocity”.

“The United States remains committed to advancing and protecting US interests in science and technology,” the State Department official added. “We have nothing further to share about the status of the agreement at this time.”

On late Thursday, the Chinese embassy in Washington said China and the US are maintaining communication on the issue. “We don’t have further comments on this,” a spokesperson said in response to an inquiry from the Post.

In the lead-up to the deadline, the Chinese embassy in Washington told the Post that “China-US cooperation on science and technology is mutually beneficial”.

“To my knowledge, the two sides have maintained communication about the renewal,” spokesman Liu Pengyu said last Thursday.

Discussion of the treaty coincides with the US presidential race shifting into high gear ahead of the November 5 election.

The race has seen Republicans accuse Democratic presidential nominee, vice-president Kamala Harris, and her running mate, Minnesota governor Tim Walz, of being too close to Beijing.

Just hours before the pact was about to expire on Tuesday, the Chinese embassy said it would “release related information at [an] appropriate time”.

“China and the US side are keeping communication on this,” the embassy said late on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, a State Department spokesperson said on background last Friday that the department was negotiating on behalf of the US government to “modernise” the agreement “to reflect the current status of the bilateral relationship”.

“We are not prejudging the outcome,” the spokesperson.

The discussion also comes amid simmering tensions on multiple fronts between the two economic superpowers.

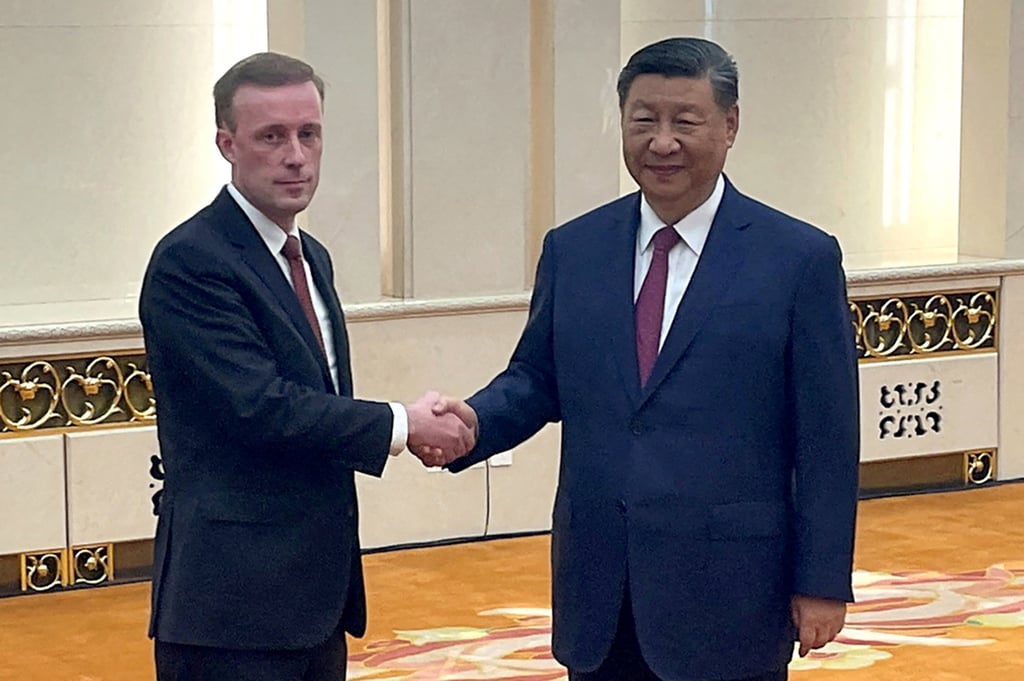

This week National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan met in Beijing with President Xi Jinping and Foreign Minister Wang Yi to stabilise bilateral relations tested by their differences over Taiwan, the South China Sea, tariffs and fentanyl.

Originally signed by US President Jimmy Carter and Chinese Premier Deng Xiaoping, the symbolically significant pact has been renewed every five years since it took effect, with the most recent renewal in 2018 under then-president Donald Trump.

After August last year, when it was on the verge of lapsing, the two countries extended it twice, for six months each time, to negotiate renewal terms.

In March, the US House Foreign Affairs Committee unanimously approved a bill to impose greater congressional scrutiny on future State Department efforts to enter, renew or extend any science and technology agreement with China.

For decades, the existing agreement has fostered scientific collaboration by providing American and Chinese researchers financial, legal and political support.

According to the Congressional Research Service, sub-agreements under the STA have encompassed research areas such as agriculture, energy, the environment, nuclear fusion and safety as well as earth, atmospheric, marine sciences and remote sensing.

Its supporters contend the deal shields American researchers working in China and enables research in the US by granting access to crucial Chinese databases, especially in areas like health studies.

But critics say China’s state supervision and control over local science and technology projects have allowed Beijing to exploit the STA.

They claim Beijing can address scientific gaps, hone skills and capitalise on America’s decentralised academic landscape to predominate in sectors like electric vehicles and renewable energy.

In June, the House select committee on China asked the Commerce department to provide information “to assess the damage already caused to US national security” caused by the STA.

“We believe the US-PRC STA is a vector to give the PRC access to US dual-use research and presents a clear national security risk,” Republican lawmakers said in a letter. “The Biden administration must stop fuelling our own destruction and allow the STA to expire.”

The agreement’s protracted renewal process after decades of uncontroversial renewals highlighted the complex new issues that have come between the two sides, according to Denis Simon of the Asian Pacific Studies Institute at Duke University.

“Many of the central issues being discussed were simply not issues in 1979, such as data security and personal security,” said Simon.

“The old STA had become almost obsolete, so renewal shifted to devising a new agreement that was more up to date and reflected the realities of 2024 and not the situation 40 years ago.”

As the US State Department and the Chinese embassy in Washington continue to say they remain engaged to work on the agreement, “at least neither side has thrown their hands up in disgust and walked out of the room”, Simon said.

On Thursday, the US deputy assistant secretary for science and space at the State Department co-chaired a meeting with Japan’s ambassador for science and technology cooperation.

They reviewed progress on cooperation in areas such as quantum, fusion and artificial intelligence and strengthened collaboration in emerging technologies including high-performance computing, according to the State Department.