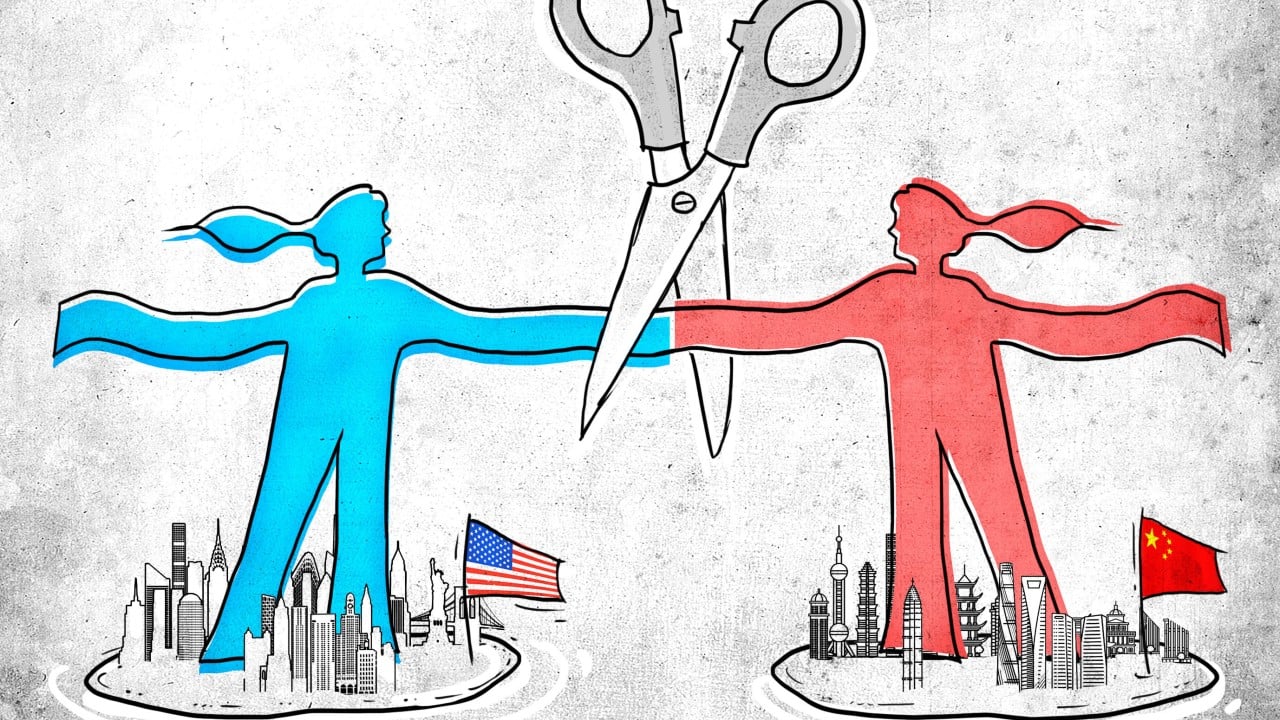

They’re an hour apart and shared the same Chinese sister city. But two US Midwestern locales have taken markedly different approaches as pressure mounts to cut ties with China.

Once seen as benign, subnational partnerships face growing opposition, with the state of Indiana the first to pass a law barring, effective July 1, new sister-city partnerships with China.

Carmel, with a population of 101,000, ended its relationship with Xiangyang, an industrial city in northwestern Hubei province. “The Chinese Communist Party will have no influence over the city,” Mayor Sue Finkam said.

Sixty-five miles (103km) away, 51,000-population Columbus held firm. “The intent and the purpose was to create a much broader understanding between two different cultures,” said Mayor Mary Ferdon. “That’s really important.”

The opposite approaches underscore diplomatic battles being fought city by city. Once a welcome source of jobs and investment, US-Chinese partnerships connecting cities, counties, states and provinces face growing US scepticism as bilateral relations tank and four in five Americans surveyed view China unfavourably.

On the national level, US Senator Marsha Blackburn, a Republican from Tennessee, and Representative Chip Roy, Republican of Texas, have introduced the Sister City Transparency Act, which would review all subnational partnerships on national security grounds.

Locally, 33 states introduced 81 bills last year restricting land purchases for Chinese nationals even as numerous communities blocked Chinese investments over national security and trade secret concerns, especially land near military sites, which number around 4,000 in the US.

US cities must juggle Washington’s often ill-defined “small yard, high fence” strategy for countering Chinese espionage, tech and trade overreach – even lithium battery joint ventures, where China leads.

“Cities are trying to figure out whether that project fits within or without the yard, and they’re nervous,” said Deborah Seligsohn, assistant professor of political science at Villanova University and formerly with the US embassy in Beijing. “We now have as much to learn from them as they have to learn from us, but we’ve set up all of the structures and our relationship as if it were a one-way street.”

While supporters advise vigilance when negotiating Chinese subnational agreements, they say these bolster economic growth, cultural understanding and environmental expertise.

Such ties flourished with China’s opening and entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, ebbing after 2016 amid trade wars and mutual distrust.

All 50 US states have seen a reduction in subnational ties with China since then, according to a recent study by assistant professors Kyle Jaros of the University of Notre Dame in Indiana and Sara Newland of Smith College in Massachusetts.

But many partnerships continue, motivated by supportive local leaders and strong economic ties.

“Sister cities are important because they highlight the importance of talking to each other,” Kimberly Bassett, secretary of the District of Columbia, said in July as the 43rd anniversary of Washington-Beijing ties was being celebrated.

Added Beijing Vice-Mayor Xia Linmao: “We welcome friends from all walks of life in DC to make new and greater contributions to subnational exchanges between China and the US.”

As of July 2022, there were 234 subnational relationships between US and Chinese cities and 50 between US states and Chinese provinces, according to the Heritage Foundation, although some may have disbanded or atrophied.

US wariness over these ties contrasts with Beijing’s enthusiasm, especially after the November summit in California between Presidents Joe Biden and Xi Jinping.

Despite Xi’s backing within his country’s authoritarian system, China has found more Washington doors closed, leading it to focus on local efforts, analysts said.

“They’re trying to go everywhere,” said Jaros. “But they’re having a hard time getting official meetings.”

At a US-China Sister City Summit in July in Washington state – co-sponsored by the civic group Sister Cities International and the Chinese government’s Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC) – some 200 Chinese attended compared with around 60 Americans.

“Just about everyone referred to the tension and difficult political environment,” said Ricki Garrett, Sister Cities International’s interim president. “But then they went on to things that they could do, people to people.”

In a video address, China’s ambassador to the US, Xie Feng, blamed American “political correctness” for undercutting sister city ties, which he said can “thaw the ice” of bilateral misunderstanding.

In contrast, the US ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, said in June that Beijing had made people-to-people exchanges “impossible” by restricting Chinese citizens’ access to US government programmes.

Some critics cite asymmetry concerns: while Western mayors and governors enjoy relative autonomy in forging overseas links, their Chinese counterparts must gain CPAFFC approval.

This pits under-resourced Western cities against China’s well-organised central government adept at furthering its human rights and geopolitical interests, critics said. They pointed to a requirement that the city of Columbia, Maryland, support Beijing’s one-China policy before partnering with Liyang in Jiangsu province.

A few cities maintain ties on both sides of the Taiwan Strait. Among Honolulu’s 36 sister cities are seven with the mainland, most forged around 2010, and one with Kaohsiung in Taiwan, established in 1962 and listed under its “China” heading.

“We are grateful for all of our sister-city relationships,” said Kaʻili Trask O’Connell, Honolulu’s cultural executive director. “Our focus is always on our areas of common interest.”

Municipalities can also be overwhelmed. After Beijing voiced a desire to “deepen subnational cooperation” with Europeans, reported Netherlands radio network BNR in 2020, a Dutch city received over 100 Chinese partnership requests in a year.

“It’s not a real city-to-city-level partnership, and it’s top-down,” said Cheryl Yu, a Jamestown Foundation China fellow. “Democratic societies should understand this before they head into any kind of collaboration because the party is using them.”

According to a US Director of National Intelligence report in 2022, China has cultivated US local leaders to bolster economic ties, influence Washington and reduce US criticism of its Taiwan, Uygur and other policies, using a “local to surround the central” strategy.

In recent years, the US has sought to address the imbalance. The FBI – which did not respond to a request for comment – likely consults with most US cities in Chinese partnerships, Jaros said. And the US State Department has tightened reporting requirements for Chinese diplomats meeting with local officials and established a Subnational Diplomacy Unit supporting local governments on national security issues.

But supporters note that US officials also meet with Chinese local officials to further soft power and influence. “The Chinese didn’t invent this idea,” said Seligsohn. “It’s gotten to the point where people view everything as suspicious.”

I really don’t think we can sustain this where everything is a national security issue

Citing the Indiana law, Jessica Bissett, senior director of the National Committee on US-China Relations, said: “Blanket legislation worries me. States and municipalities need to make the decisions that are best for them. We think they’re smart enough to do that.”

“I really don’t think we can sustain this where everything is a national security issue,” she added.

The calculations that Carmel and Columbus made reflect a conservative state where China has seen a decidedly mixed reception. In September, Indiana’s state pension fund voted to divest from China, and in July it banned Chinese land ownership.

The sister city law, initially a few sentences slipped into a 112-page tax bill, does not mention China by name. But it bars ties with “foreign adversaries”, which typically refers to China, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, Russia and Venezuela. Indiana reportedly has 19 sister city agreements with Chinese cities, although some appear dormant.

Carmel formed its partnership with Xiangyang in 2012, inspired by then-mayor Jim Brainard. Last fall, shortly before stepping down after three decades, Brainard revisited Xiangyang to bolster ties.

“Although there are issues of disagreement between China and the United States, it is vital to talk to each other,” he said before leaving.

But when US Representative Jim Banks of Indiana learned about the trip, he pressured Brainard’s replacement, Finkam, to “undo others’ mistakes” and end the programme. Banks, a China hawk, also serves on the House Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party.

Banks also urged Finkam, a fellow Republican, to avoid China trips, end Carmel’s membership in the pro-engagement US Heartland China Association and otherwise “distance itself from the Chinese Communist Party”.

Things soon got personal. Banks accused Brainard of being “wined and dined – expensive liquor, massages” on his trip to China. Brainard criticised Banks’ comments as “symptomatic of the dumbing down of America” and “simply immature”.

Finkam cut ties with Xiangyang – although the state law only bans new partnerships – adding that the move was not directed at local “freedom-loving” Chinese-Americans.

The mayor declined an interview but said in a statement: “I take the safety of our nation and city very seriously,” noting that Carmel, with a sizeable Asian population, will retain its popular mooncake festival.

Carmel, Columbus and Xiangyang share similar economies built on agriculture and manufacturing, although Xiangyang’s 1.8 million population dwarfs the other two.

Anchoring Columbus’s decision to continue its Xiangyang partnership are long-standing ties. Its largest employer, engine-maker Cummins, sent its first delegation to China in 1975, established a Beijing office in 1979, exports extensively and has long collaborated with Xiangyang-based Dongfeng Motor, Foton Motor and other carmakers.

American cities should be aware they are not dealing with independent Chinese cities free of party influence. But Washington and Beijing also need to avoid injecting excessive geopolitics into partnerships and clarify national security boundaries, said Jaros.

“We’re at a kind of desperate moment,” he said. “We need basic forms of contact and mutual understanding albeit with the idea that we’re not going to agree on everything and that we do have to be cautious.”

Others have a more existential view.

“I realise that the relationship between China and the US is not particularly good right now,” said Garrett of Sister Cities International, which sprang from US president Dwight Eisenhower’s People-to-People conference in 1956. “But, we think, if people get to know each other personally, it helps prevent wars.”