Chen Yulu never thought her home province of Hunan had any culture that she would be proud of, much less become an ambassador of.

But these days, the 23-year-old is a self-proclaimed ambassador of nushu, a script once known only to a small number of women in central China.

It started as a writing practised in secrecy by women who were barred from formal education in Chinese. Now young people like Chen are spreading nushu beyond the women’s quarters of houses in Hunan’s rural Jiangyong county, whose distinct dialect serves as the script’s verbal component.

Today, nushu can be found in independent bookstores across the country, transport advertisements, craft fair booths, tattoos, art and even everyday items like hair clips.

Nushu was created by women from a small village in Jiangyong, in the south-central province where late Chinese leader Mao Zedong was born, but there is little consensus on when it originated. Scholars estimate the script is at least several centuries old, from a time when reading and writing were deemed male-only activities. The women developed their own script to communicate with each other.

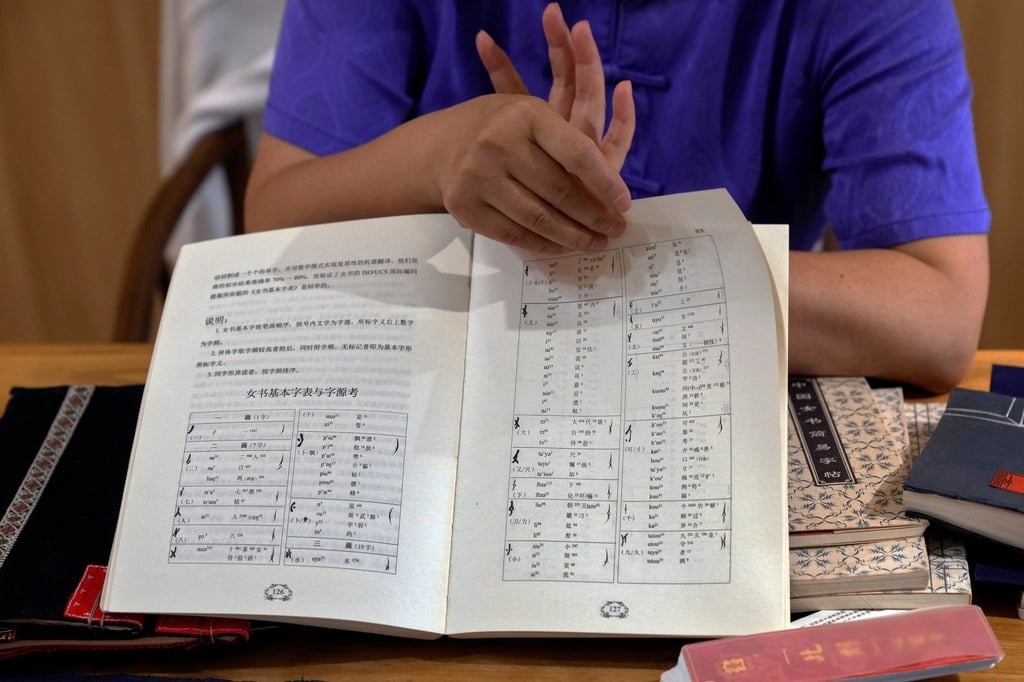

The script is slight with gently curving characters, written with a diagonal slant that takes up much less space than boxy modern Chinese with its harsh angles.

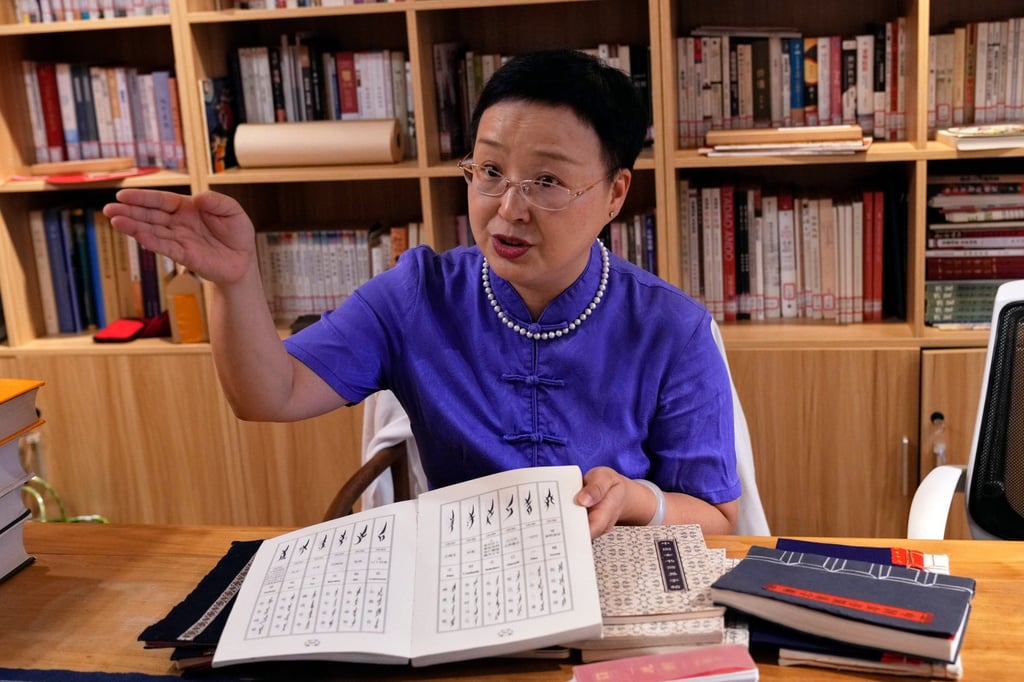

“You won’t allow me to go to school. OK, I get it. So what’s my way out? I’ll find ways to educate myself,” said Xu Yan, 55, the author of a textbook on nushu.

Women lived under the control of either their parents or their husband, and used nushu, sometimes called “script of tears”, in secret to record their sorrows: unhappy marriages, family conflicts, and longing for sisters and daughters who married and could not return in the restrictive society.

Xu is also the founder of Third Day Letter, a nushu studio in Beijing named after a centuries-old practice of the script’s practitioners. The third-day letter is a hand-sewn book presented in farewell to a woman in Jiangyong on the third day after her marriage, when she is allowed to visit the childhood home she left.

The script became a unique vehicle for composing stories about women’s lives, typically in the form of seven-character line poems that are sung. A secret world sprang from the script that gave Jiangyong women a voice through which they found friends and solace.

That secret world still resonates today as a source of strength for young women dissatisfied with patriarchal constraints.

Chen, who studied photography at an art school in Shanghai, said her male professors often doubted that she could keep up with the male photographers because of her slight physique. That attitude, she said, is “in every aspect of life, there’s nowhere it doesn’t touch”.

She was frustrated but did not see much room to retaliate – until she learned about nushu.

“I felt that I had received a very strong power, and I think a lot of women need this power,” she said.

Chen wanted to make a documentary about feminism and came across nushu in her online search. When she realised the script originated from Jiangyong, just a few hours from her hometown, she immediately knew that she had found her graduation project’s topic.

The more she learned about this script, the more she learned about its duality: that it was as much a painful thing as it was a source of strength.

In her documentary, she follows He Yanxin, a formally designated inheritor for nushu who is now in her eighties. She asks Chen: “Do you think nushu has any use?” Chen says yes. In response, He says: “Nushu is useless.”

He comes from Jiangyong and says she was forced to marry a man she did not want to be with, who physically abused her and tore up photos from nushu meet-ups and workshops she attended. She did not feel that the script had made her life materially better, according to Chen’s first-person account, published on social media.

Yet He is the one who urged her to learn the script.

Formal inheritors of the script have to be from Jiangyong, Chen said, and have to master nushu, but there was nothing stopping her from sharing her love of the script with others.

Beginning in 2022, Chen began spreading the practice. She started an online nushu group, taught writing workshops and set up nushu art exhibitions in cities across China.

Most participants at her writing workshops are women, she said, and some people even bring their mothers. Chen also runs a social media account to promote nushu and its culture beyond Hunan.

Lu Sirui, a 24-year-old working as a marketer, learned about nushu from online feminist groups and joined Chen’s nushu-focused group on messaging platform WeChat.

“At first, I just knew that it was a women’s inheritance, belonged only among women,” Lu said. “Then, as I got to know it better, I realised that it was a kind of resistance to traditional patriarchal power.”

For Lu, nushu means “a very powerful rebellion” and a bond of sisterhood. She said it was important for women to stick together.

Lu once encountered a property agent in Beijing who, drunk in the middle of the night, knocked on her door and tried to enter her home. Lu said that she picked up a stick at the doorway and ran out to confront him.

Afterwards, she confided in a small feminist community online, where she received comfort and advice on how to handle the situation.

She says communities like that have supported her in the face of gender-based violence, inequality and mother-daughter relationship problems, among other challenges.

Seeing nushu as another representation of sisterhood, Lu bought a textbook and practises the script in her spare time. Even though she is not a formal nushu ambassador, she began hosting nushu workshops at bookstores and bars in Beijing. When organising these events, Lu discovered that very few people had heard of nushu, but the feedback was always positive.

“It’s a manifestation of female strength that transcends time and space,” Lu said.