Towering skyscrapers, candy-coloured public housing blocks, and lush green spaces – Singapore has long been recognised for its meticulous urban planning.

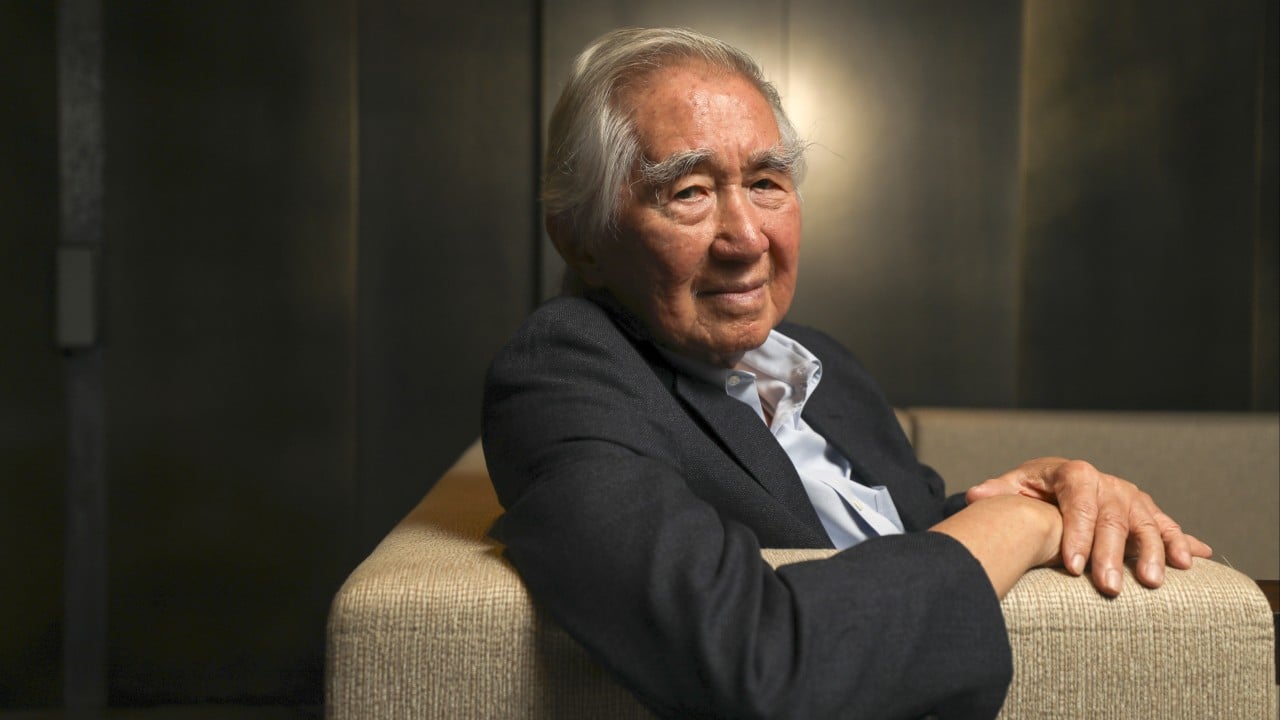

The city state is home to a population of 5.9 million people despite spanning just 284 square miles, and much of the credit for the city’s layout goes to Liu Thai Ker, 86, an urban planner who’s often considered the architect of modern Singapore.

During his time at the Housing Development Board, (HDB), Liu oversaw the building of 20 new towns and over half a million housing units in the city. In the late 80s and early 90s, he also served as the chief planner of the Urban Redevelopment Authority, where he developed Singapore’s land-use plans.

And yet, Liu has said he has two regrets about how Singapore was planned.

“When I was in the HDB, I raised the issue of planning bicycle paths for citizens,” Liu said.

“At that time, my colleagues and I had several discussions, but eventually decided against it due to Singapore’s tropical climate, which we felt would be too hot for cycling.”

The Singapore government is planning to double the city’s existing cycling network by 2030.

However, the attitudes of Singaporeans and people around the world today have changed, he said.

Liu says he wishes he had developed bike sections for roads and incorporated bicycle paths into streets. “Fortunately, I believe it is still possible to do so,” he added.

In 2023, The Straits Times reported that local authorities are planning to double the city’s existing cycling network from 530km now to 1,300km by 2030.

Integrating more bicycle paths would enhance Singapore’s sustainability efforts, aligning with global trends in urban development seen in cities like Copenhagen and Amsterdam, Thomas Schroepfer, a professor of architecture and sustainability design at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, said.

Shared tracks – for pedestrians and cyclists – are commonly found in parks and other recreational areas in Singapore.

“Creating bicycle paths is crucial for sustainable cities and would benefit Singapore by reducing traffic congestion, lowering emissions, and improving public health through increased physical activity,” Schroepfer said.

Additionally, bicycle paths can boost local economies, as cyclists are more likely to stop at local businesses, he said.

Singapore’s skyline today includes some world-famous builds.

There’s the Marina Bay Sands and its infinity pool. There’s the Oasia Hotel in downtown Singapore, which has been called a “living tower” for the greenery that’s intentionally overgrowing its 620-foot facade. And there’s Esplanade, a theatre by the Singapore River that’s nicknamed “The Durian” for its resemblance to the tropical fruit.

But in the 60s, Singapore looked drastically different.

According to the Ministry of National Development, an estimated 300,000 people lived in semi-permanent shelters in squatter areas, while another 250,000 were in rented partitioned cubicles in old shophouses.

While there are no longer any squatter settlements in Singapore, other architectural features, such as shophouses, have been conserved.

Through HDB, the government managed to rehouse around 1.2 million squatters by 1985, Liu said.

“While it is a very gratifying achievement, my regret is that we did not attempt to save a few hectares of the original squatter colonies for Singaporeans of today, and future generations to see how far we have transformed the city to its present condition,” Liu said.

“No amount of photographs or written text, can convey adequately the poor living conditions of our squatters in the early days,” he continued.

“As we always say, seeing is believing. While regretfully, we can no longer see our squatter colonies today, this also implies that Singaporeans are living in much better conditions.”

Indeed, Singapore’s public housing flats are home to about 80 per cent of the country’s resident population today.

While there are no squatter settlements in Singapore any more, other old architectural features, such as shophouses and black-and-white colonial bungalows, have been conserved.

However, the purpose of preservation should be to encourage the younger generation to think about who they are as individuals and as a society, Rita Padawangi, an associate professor at the Singapore University of Social Sciences, said.

“Squatter huts are probably a reminder of the need for supporting infrastructures so that people do not take for granted the basic standard of living that is almost universal in Singapore, which is a tremendous achievement,” she said.

“But we must also think about the people who live in these old homes when they are preserved, because preservation is only meaningful when the place is lived in.”

Pulau Ubin is a small island situated in the northeast of Singapore. It is one of the last rural areas to be found in Singapore.

Instead of conserving squatter settlements – where people lived in squalid conditions – it’ll be better to conserve the “kampongs,” or villages, of Singapore instead, she said.

She added that this would allow younger generations to learn about urban change, what Singapore has achieved, and what has been lost along the way.

Two places in Singapore, she added, still come to mind when locals think about the old days: Kampong Lorong Buangkok, the last traditional village in Singapore, and Pulau Ubin, a small island off the northeast coast of Singapore that’s home to around 38 villagers.

“They are still around, not because they are purposely preserved. These two places are still lived in, and that is why they become meaningful,” she said.

Singapore already has an efficient waste-management system and advanced water-management strategies like rainwater harvesting, desalination, and waste water recycling, Schroepfer said.

At the same time, the city has been criticised for its heavy reliance on air conditioning – which puts a strain on the environment but also provides relief from the hot and humid climate, where the average daily temperature is about 82 degrees Fahrenheit.

The city has been criticised on the sustainability front for its over reliance on air conditioning.

In recent years, the government has been ramping up its efforts to improve the city’s district cooling system, in which a centralised chiller plant is used to cool multiple buildings through a network of underground pipes carrying chilled water.

However, to future-proof the city for challenges such as climate change and population growth, there are other measures that Singapore can take, Schroepfer added.

This includes reducing waste generation and lowering water consumption, as well as enforcing higher sustainability standards for all new buildings while retrofitting older ones, he said.

“Urban planning should prioritise sustainability, inclusivity, and resilience. Integrating green spaces, efficient public transport, and renewable energy sources are crucial,” he added.

This article was originally published by Business Insider