The New York-based foreign policy think tank known as the Council on Foreign Relations has launched a new project called the China Strategy Initiative. According to its website: “Competition with China poses a challenge unlike any the United States has faced before.” The initiative will aim to “answer the questions that go to the heart of American China strategy”.

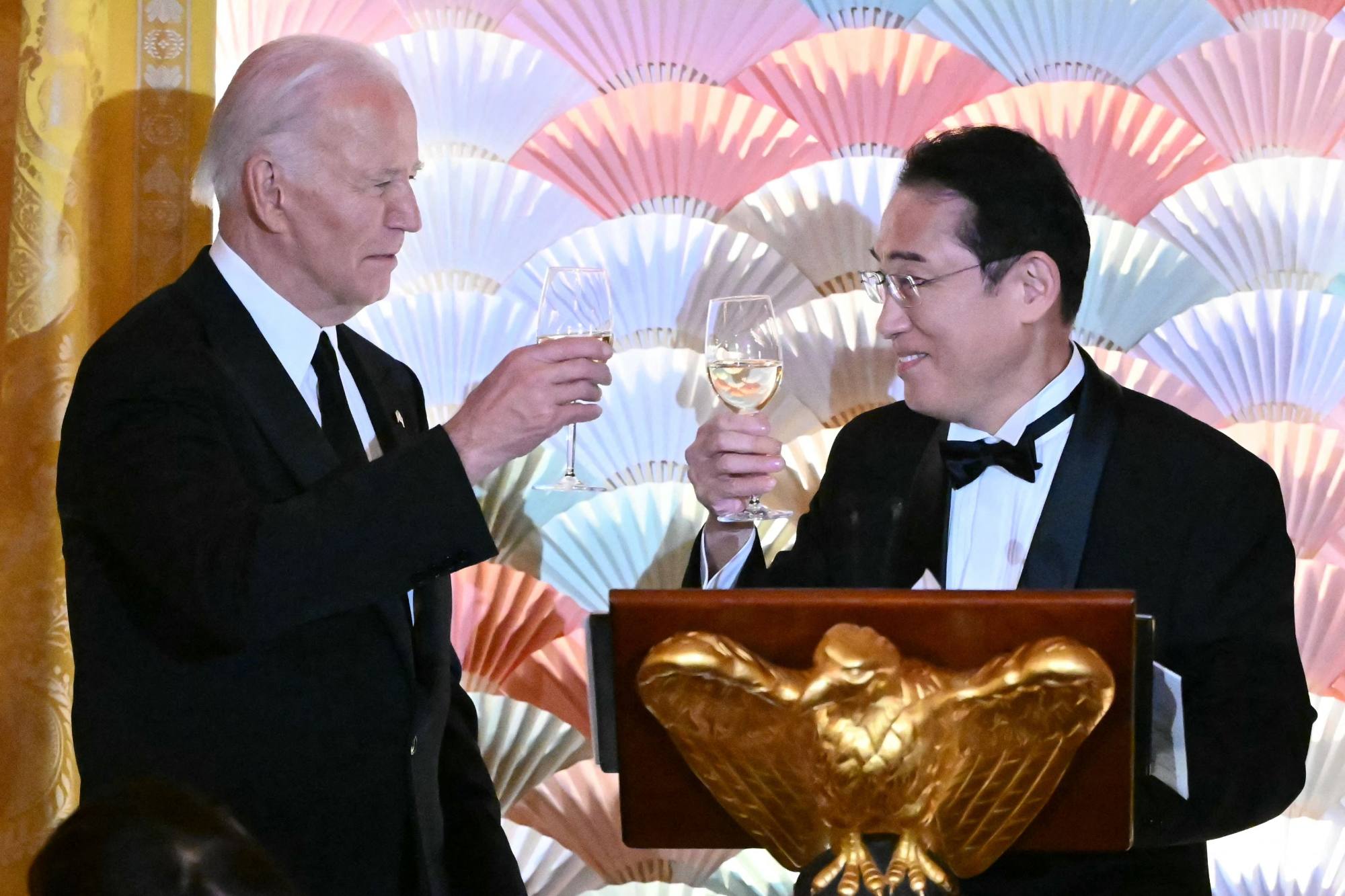

This initiative speaks to an overriding US imperative to re-engage a battle of the narratives that can credibly unify as many as possible of its key allies in explaining exactly why China’s rise constitutes an existential threat to the globally benign status quo.

Winning the narrative battle has been pivotal to governments justifying their rule throughout recorded history, and today is no different. That is why victors always write the history books: the story is often more important than the truth.

This Council on Foreign Relations initiative is likely to be important, partly because some inconvenient truths are undermining the credibility of the US narrative. The unifying narrative that has lent authority to the US claim to global leadership since World War II seems increasingly threadbare.

Since the defeat of the Axis powers and the creation of the United Nations and other Bretton Woods Institutions, the US has worked brilliantly to generate a steady narrative justifying the “rules-based order”, which has provided a unifying story for the maintenance of peace and global prosperity. As Alexandra Homolar and Oliver Turner wrote in Oxford Academic in January, this delineated a “morally superior grouping” that “established a benign and mutually beneficial system of international organisation”.

“Overall, the [rules-based order] origin story is one of peace, stability and prosperity”, they wrote. It provided what they call “a unifying story for the maintenance of formal security alliances” that has been “dividing the world into those who belong to the community of righteous actors and those situated outside”.

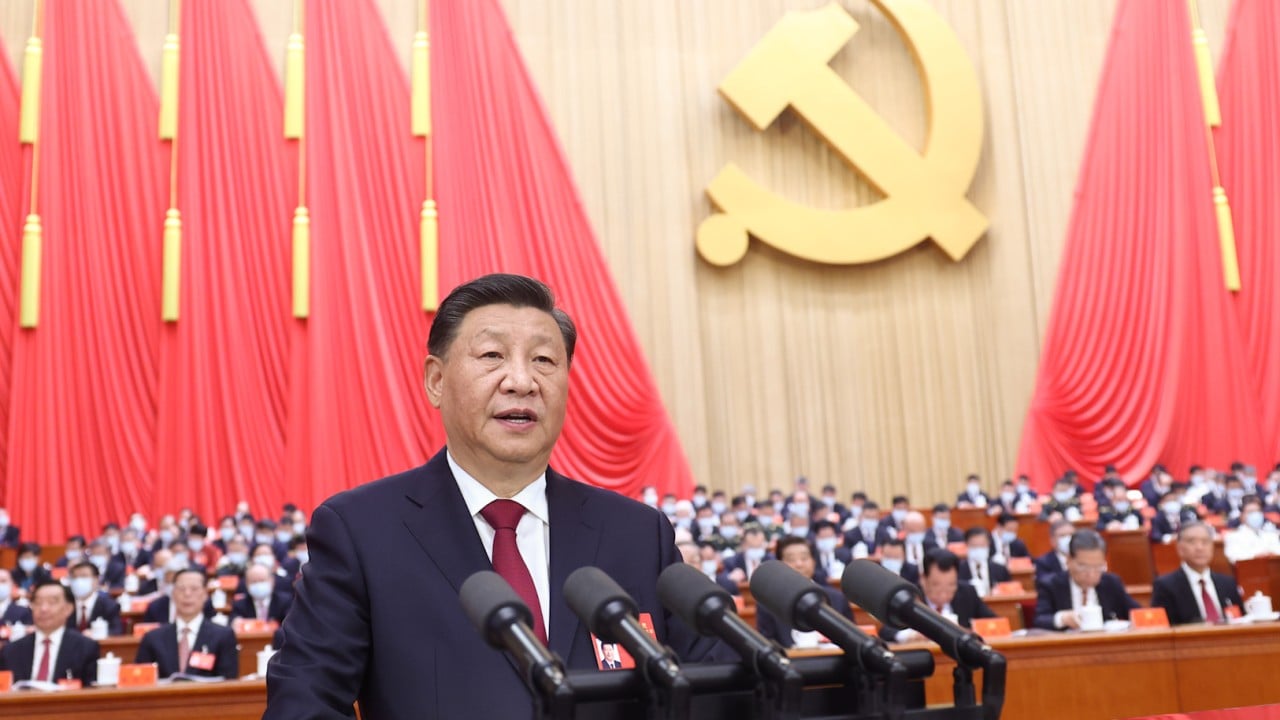

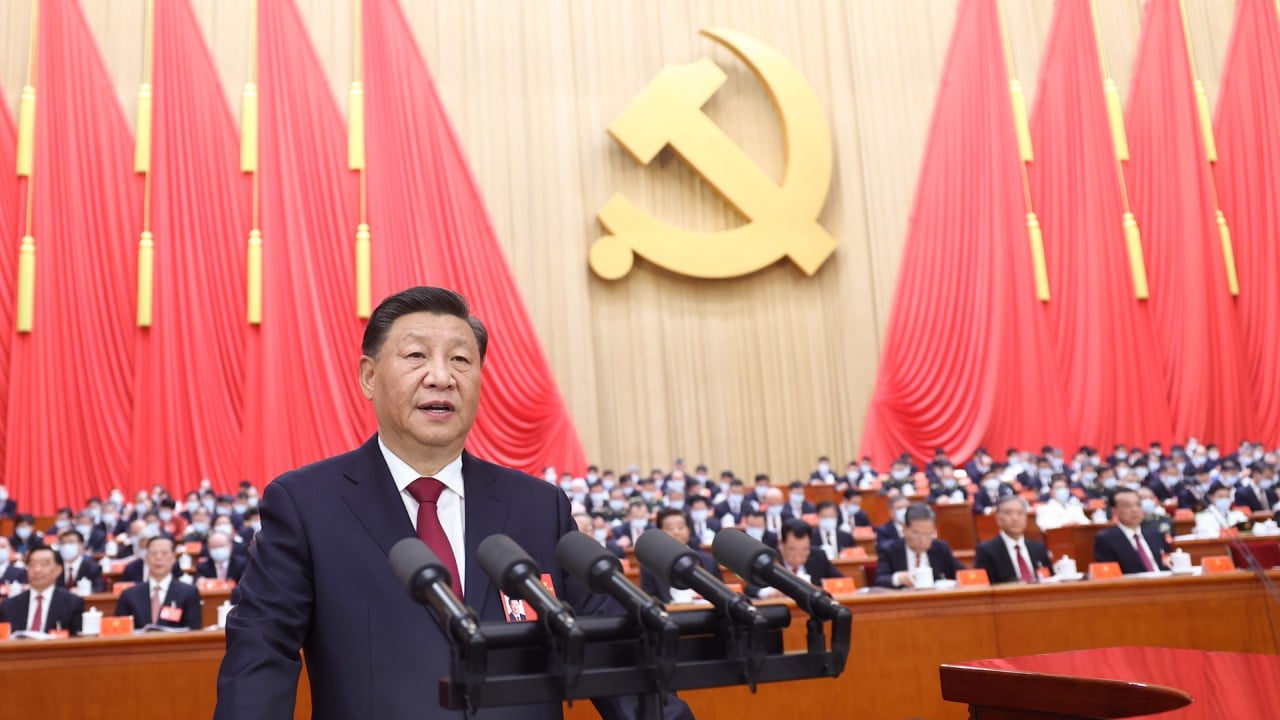

This narrative has been repeated by the Biden administration, in particular by US secretary of state Antony Blinken. Recall Blinken’s 2022 speech at George Washington University: “China is the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military and technological power to do it.”

He framed China as an aggressive and expansive one-party state whose “vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress over the past 75 years”.

This narrative persists, despite a lack of evidence of military aggression or territorial expansion that would lend it credibility. It is reinforced by claims that China is part of an “axis of evil” comprising China, Russia, Iran and North Korea, and that it is manipulating trade and investment rules with subsidies and protectionist industrial policies, intellectual property theft and “debt-trap” diplomacy.

While all of these claims are underpinned by dubiously concocted facts, and often no facts at all, this does not matter. In the battle for narrative control, the quality of the narrative counts more than the facts.

Over recent years, the US has masterfully created, fuelled and nurtured such narratives, served by think tanks, often based in Washington and well-funded by a wide range of interest groups. Some are more independent than others.

The Council on Foreign Relations is one of America’s most impressive focal points for discussion and analysis of international affairs. The leader of its China Strategy Initiative, Rush Doshi, has impeccable credentials – degrees from Princeton and Harvard and experience at the State Department and the White House. He previously served as the director of the Brookings China Strategy Initiative.

But it is unclear if the Council on Foreign Relations initiative is setting out to burnish a narrative that no longer seems to be working as well as it should, or if it will edit that narrative to make it more credible not just to China, but to a growing number of countries in the Global South that are now queuing to join supposedly unaligned bodies like the Brics or the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation.

As Vu Le Thai Hoang and Ngo Di Lan at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam contend, the gap between the US narrative on China and China’s own narrative is too large to not be reconciled. How will the Council on Foreign Relations initiative be able to provide better facts to underpin the charges that China constitutes an existential threat?

How willing will Doshi’s team be to examine China’s own narrative claims – that it is focused on economic recovery after a century of national humiliation, that the US is acting to “contain” China’s recovery and is meddling in China’s domestic affairs and that China’s rise is infused with mutual respect and peaceful coexistence.

In a world where actions speak louder than words, and where social media has the embarrassing capacity to scrutinise false narratives, the initiative will do great good if it can re-audit the often-specious evidence of the rules-based order, not to satisfy officials in the State Department, but to satisfy leaders across the Global South who have experience of a China different from the one described so messianically by Washington.

Perhaps Yale Law School senior fellow Stephen Roach has a point when he says there is neither a China problem nor a US problem, but a relationship problem that needs a relationship solution. I am sure he could weave a narrative for that.

David Dodwell is CEO of the trade policy and international relations consultancy Strategic Access, focused on developments and challenges facing the Asia-Pacific over the past four decades