On Dec. 31, 2025, a Vietnamese court convicted and sentenced prominent political dissident Nguyễn Văn Đài to 17 years in prison under Article 117, which criminalizes what the law terms “propagandizing against the state.”

For observers of Việt Nam’s human rights record over the past decade, his name is a familiar one. This was not Nguyễn Văn Đài’s first conviction for political activity, nor even his second; it marked the third time he had been convicted for dissent in the country.

Đài was first arrested and sentenced to four years with four years probation for “propagandizing the state” in 2007. Ten years ago, on Dec. 16, 2015, Đài was arrested for the second time and later sentenced in April 2018 to 15 years in prison, followed by five years of probation.

Just two months later, on June 7, 2018, he was released from custody and allowed to leave Việt Nam for Germany, where he was granted political asylum; he has remained a resident there ever since.

Despite his absence from the country, the Vietnamese authorities ironically tried Đài in absentia on Dec. 31, 2025, imposing a new 17-year sentence on him.

The third sentence came more than five years after the EU–Vietnam Free Trade Agreement entered into force, underscoring that Việt Nam’s prosecution of high-profile dissidents has continued unabated during the EVFTA era.

In the last decade, Việt Nam arrested and tried almost 500 individuals for raising their voices, according to The Vietnamese Magazine’s dataset, compiled mainly from Project 88’s database and social media.

Việt Nam’s Jailing of Dissident Voices Over the Past Decade

The data we compiled for this article shows that from 2015 to 2025, Việt Nam has followed a clear pattern of punishing political prisoners, marked by waves of arrests, frequent use of arbitrary laws, and consistently severe prison sentences year after year.

Along with changes in the number of arrests, this time period shows a stronger use of laws to punish people who speak out, based on information gathered from court records, human rights reports, and independent news sources.

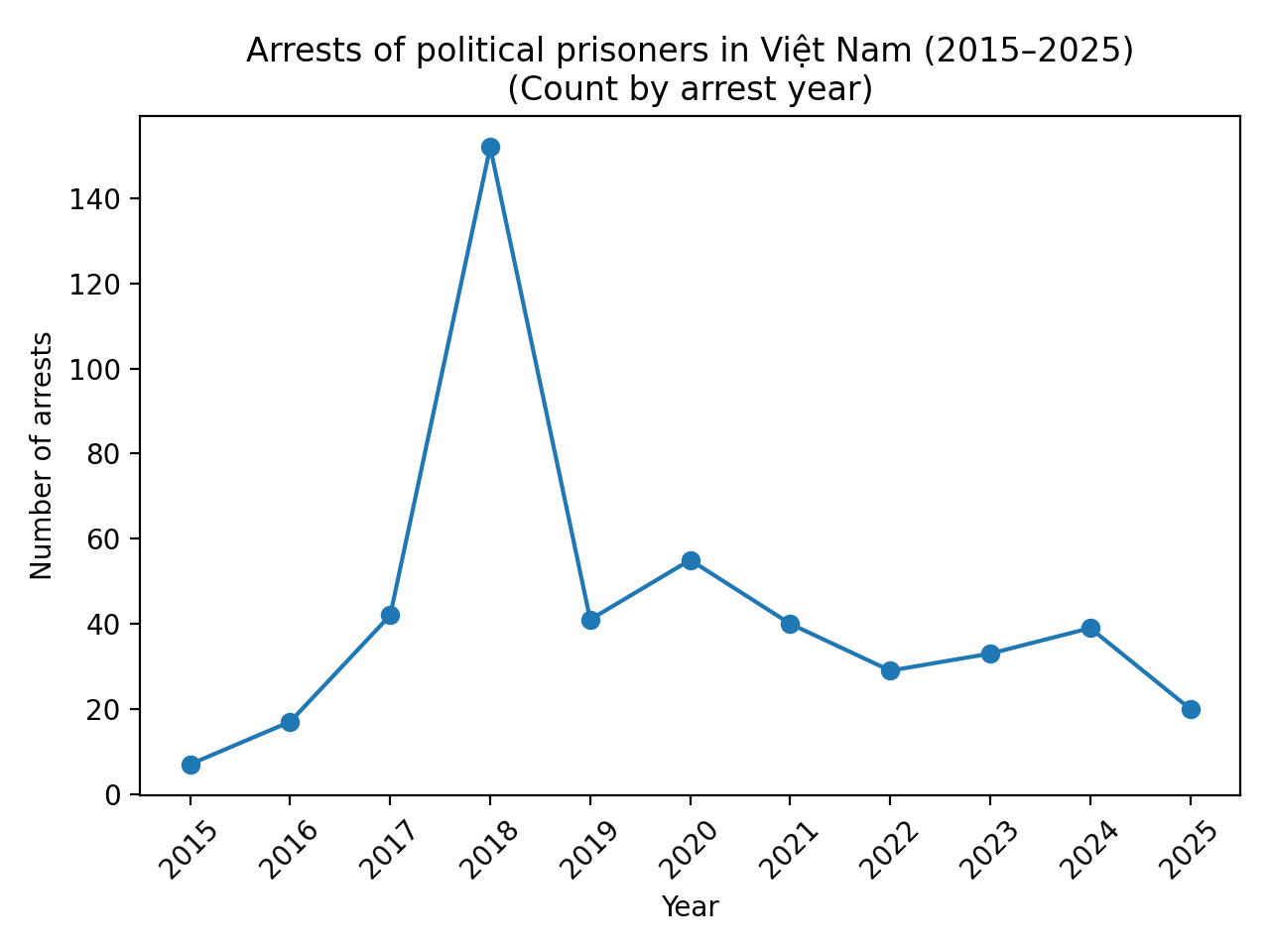

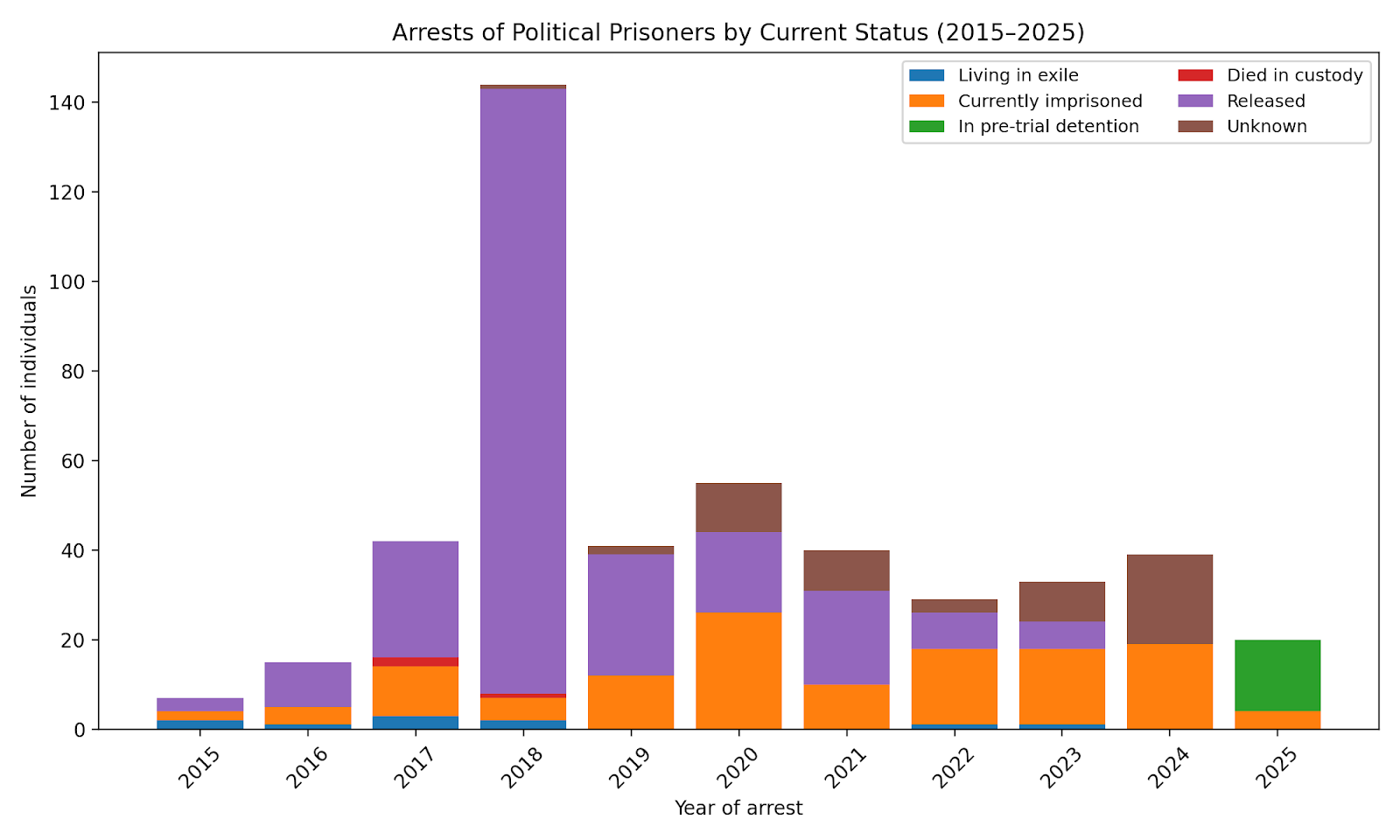

There is a sharp surge in arrests in 2018, which stands out as the peak year in the decade under review. The spike coincided with heightened political sensitivity surrounding nationwide protests and growing online activism.

One of the reasons for the surge of arrests and convictions in 2018 was the biggest protest in Việt Nam since 1975, which happened on June 10, 2018. At the time, widespread and largely unplanned protests erupted across major cities in the country, Hà Nội, Sài Gòn, Đà Nẵng, Nha Trang, and others.

Thousands of ordinary citizens, not led by well-known dissidents, took to the streets to oppose controversial draft laws on Special Economic Zones and cybersecurity, which they feared would undermine sovereignty and civil liberties.

On that day, participants livestreamed their actions on social media, cited constitutional rights such as Article 25 of Việt Nam’s Constitution to challenge police detentions, and remained peaceful even in the face of police crackdowns.

Some observers saw the event as a rare instance of grassroots civic involvement in Việt Nam’s tightly controlled political climate since it demonstrated a level of political knowledge and collective action. Unfortunately, the Vietnamese government responded with crackdowns, arrests, detentions, and the sentencing of numerous individuals to prison in 2018.

Even if the number of arrests went down after 2018, they never went back to the comparatively low levels seen before 2015–2016. This suggests that the time following 2018 is not a retreat but a recalibration of repression.

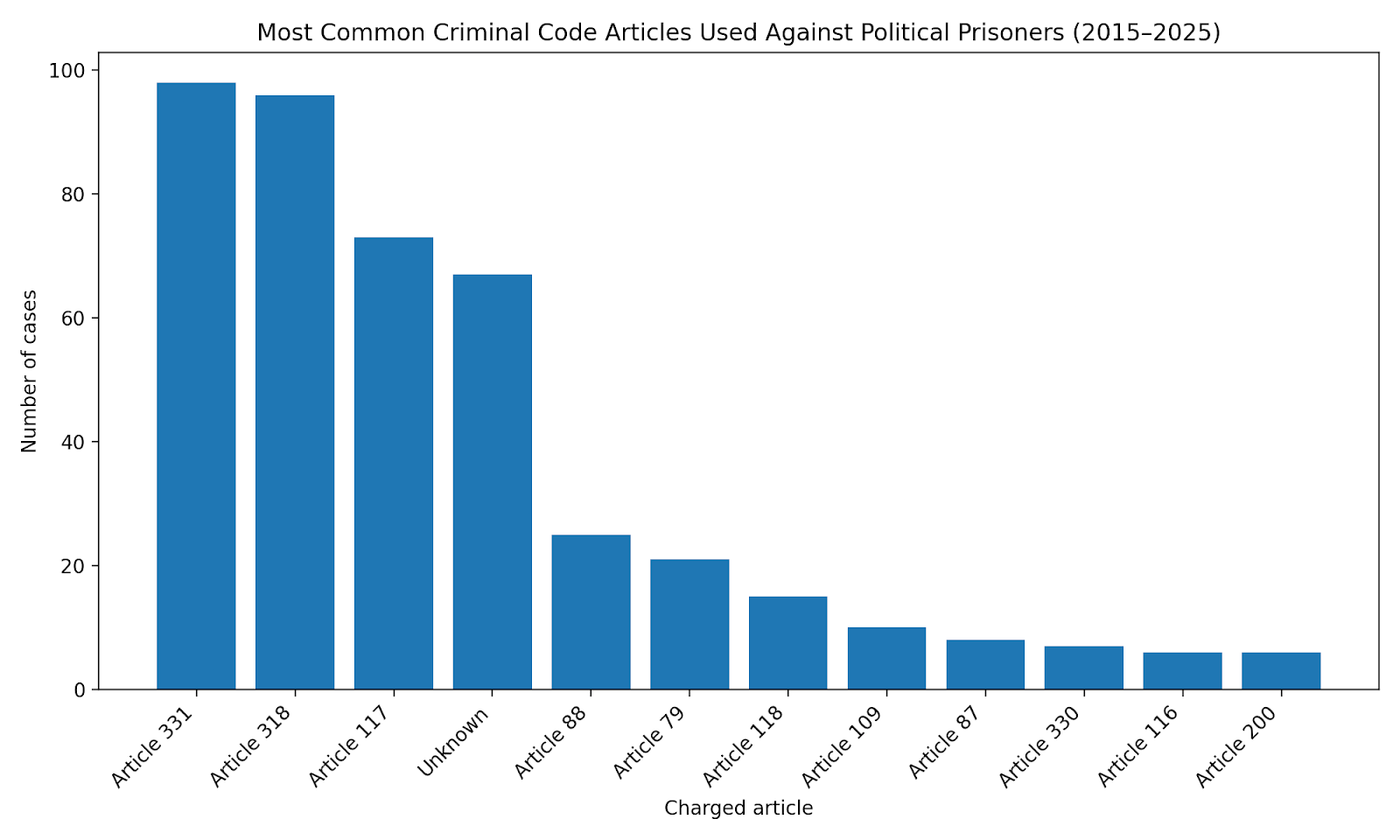

An examination of the criminal code articles most frequently used against political prisoners underscores the legal architecture of this repression. Article 331 (“abusing democratic freedoms”), Article 318 (“disturbing public order”), and Article 117 (“making, storing, or disseminating information against the state”) dominate the dataset.

The prevalence of application in political cases demonstrates how Việt Nam is treating its dissenters, which is less about specific acts of violence or incitement and more about controlling expression, association, and peaceful civic engagement.

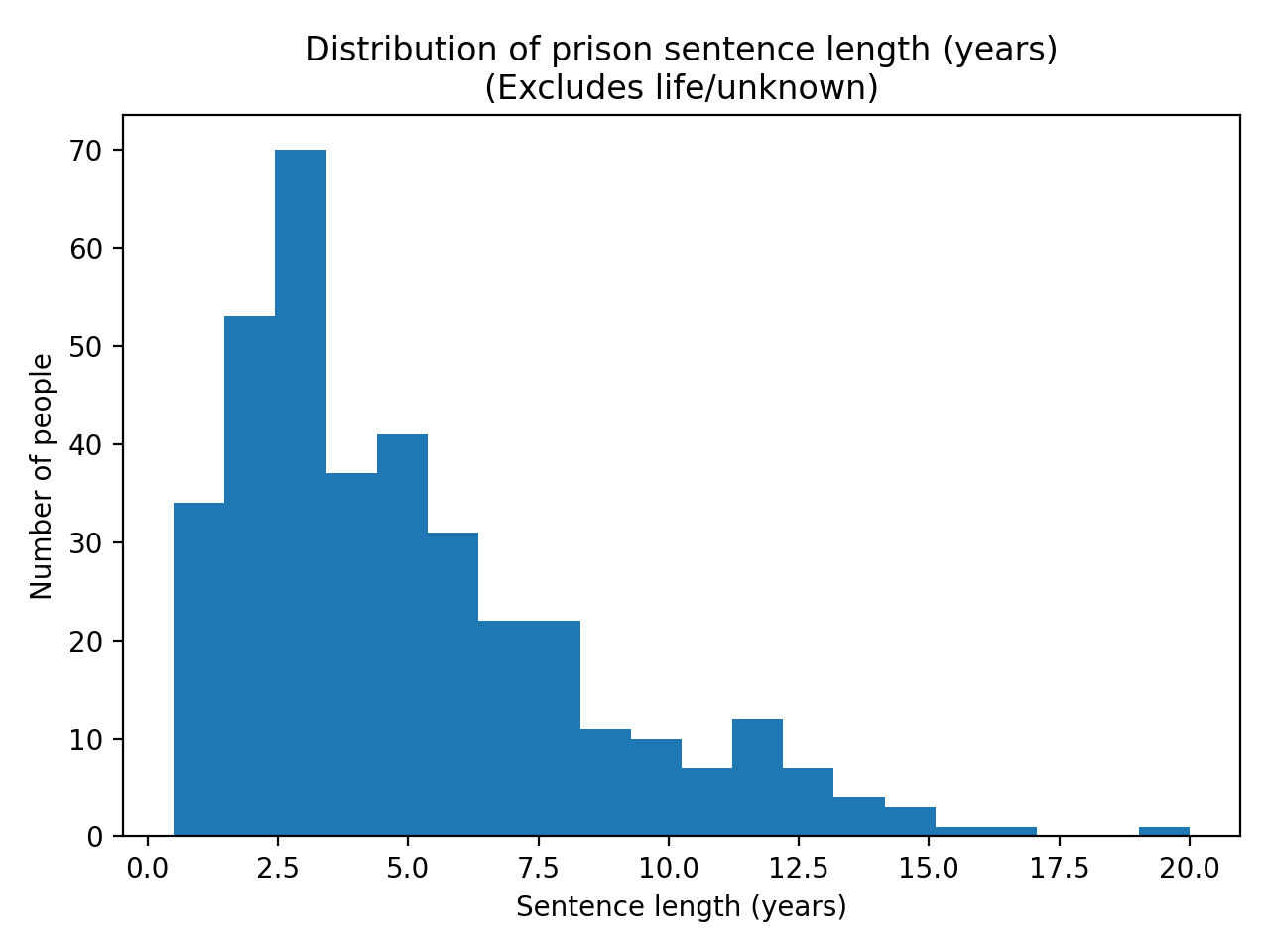

The information above about sentencing provides an equally grim picture. Prison sentences for political prisoners are always long, and they are often calculated in years instead of months. Median sentence lengths change from year to year, but they are always harsh, with some people getting terms of more than ten years.

We don’t include life sentences or sentences that are unknown in the graph above. There were, however, reports of deaths while in detention, though they were fewer in number. This graph illustrates the severity of charges imposed on individuals accused of political crimes.

There are more short sentences in subsequent years, but they sometimes come with longer pretrial imprisonment or further restrictions on freedom after release.

Current status data makes the story much more complicated. A lot of the people who were arrested between 2015 and 2025 are now classified as “released,” but it does not mean they were found innocent or given back their freedom.

Many people who have been released from prison are still on probation, being watched, not allowed to travel, or under other forms of post-release supervision.

At the same time, many people are still in jail or in pre-trial custody, which shows how long the repression lasts after the first arrest. For instance, look at the case of Nguyễn Văn Đài in 2015. He was taken into custody on December 16, 2015, but his trial didn’t occur until April 2018. Before his case went to trial, he spent almost three years in prison.

Nguyễn Văn Đài’s case is one of the pieces of evidence that indicates that the system depends less on short-term crackdowns and more on long-term, legally organized pressure when all the data is looked at together.

The similar types of charges, the long sentences, and the consistent use of detention during different political periods show that repression is a normal way of governing, not just a rare action.

From an investigative perspective, the data indicate that Việt Nam’s political prisoner cases are not isolated occurrences but rather components of a systematic, enduring plan to suppress dissent and regulate civic space via its criminal justice system.

A Decade of Arrests Tied to Online Expression

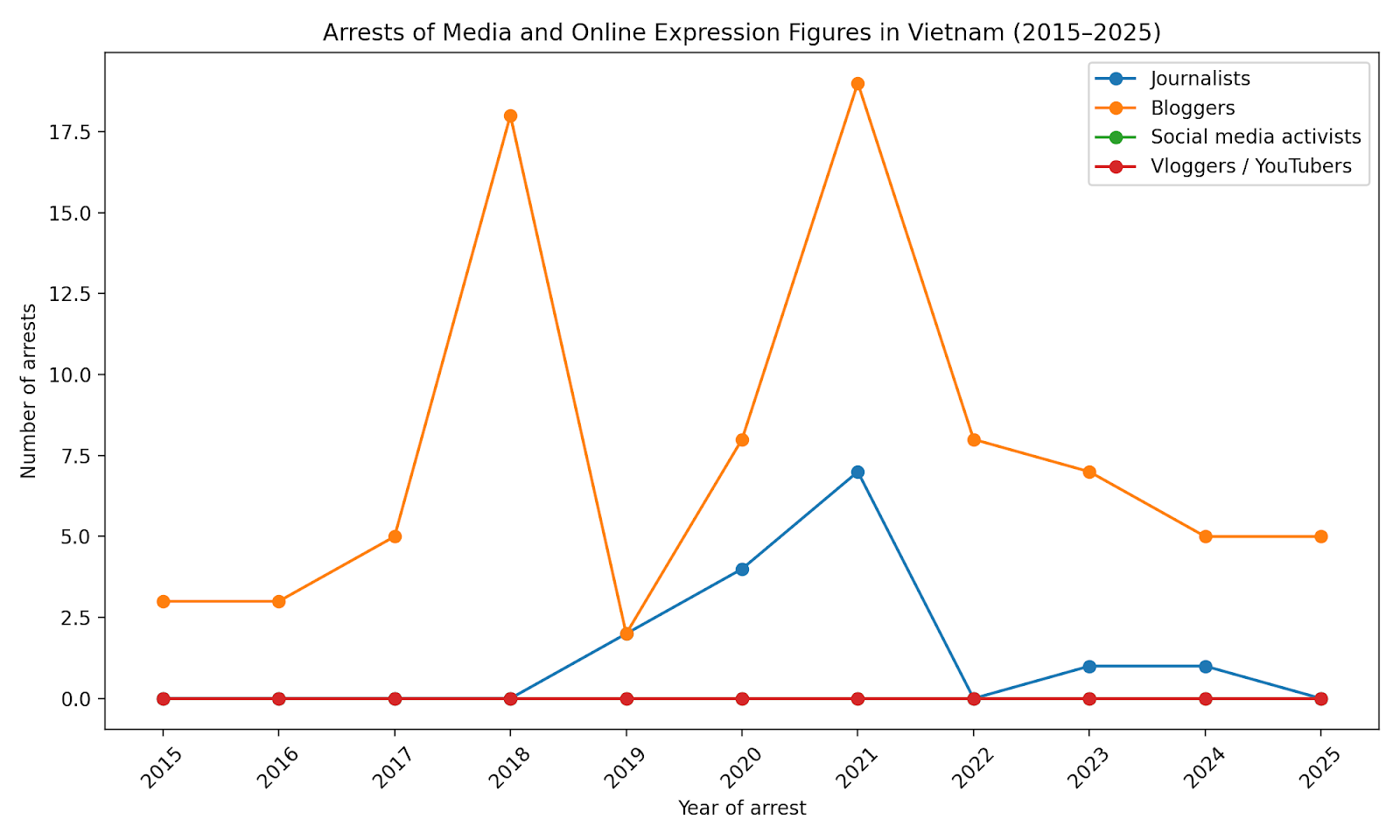

Arrests linked to journalism and online expression in Việt Nam increased sharply in 2018 and continued to grow in the years that followed, according to data compiled from court records, human rights groups, and media reports covering the period from 2015 to 2025.

The dataset shows that independent bloggers were held responsible for the most cases each year, and arrests were made every year for the past ten years. Protests and rising political tensions around the country coincided with a spike in arrests in 2018. However, arrests remained even after the turmoil died down.

Professional journalists were less common in the records, but arrests went up after 2020 as the government paid more attention to reporting and criticism that wasn’t in state-controlled media.

Phạm Chí Dũng, Nguyễn Tường Thụy, Lê Hữu Minh Tuấn, and Phạm Đoan Trang were some of the most well-known journalists who were arrested during this time. The arrests, which took place in late 2019 and throughout 2020, led to prison sentences of nine to fifteen years, which is one of the heaviest punishments for journalists in recent years.

The whole editorial crew of Báo Sạch (Clean Newspaper), an independent online news site, was also detained between 2020 and 2021. Each member of the group got more than three years in prison. This shows how the government is cracking down on independent journalism in general, not just in high-profile cases.

The dataset’s numbers also reveal that the government has primarily targeted written content on the internet for enforcement. The timeline indicates that arrests related to expression were not just made during short periods of political instability. Instead, they happened again and again across many years and political cycles.

Việt Nam’s Arrests of Dissenters Show Sustained Crackdown Over a Decade

Data collected on arrests from 2015 to 2025 show that the Vietnamese government has been systematically cracking down on people who are exercising their rights to free speech, free association, and peaceful participation in civil society. These rights are protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Vietnam is a party to.

In the early years of the period studied, the number of recorded arrests stayed low, with only seven in 2015 and 17 in 2016. But we should be careful since these numbers don’t always mean that things are getting better; they could mean that prior cases weren’t fully documented.

In 2017, arrests surged substantially to 43 cases. This marked a shift from isolated events to a more concerted pattern of enforcement targeting independent voices.

The trend reached its peak in 2018, when there were 152 arrests, which was several times more than in previous years. The rise happened at the same time as rallies around the country and more instability in the community, as well as a wider use of broadly defined “national security” measures.

In 2018, the number and severity of criminal cases against peaceful expression reached a new level. This is against ICCPR guarantees for free speech and assembly.

From 2019 to 2024, there were between 28 and 56 cases per year. This suggests that the suppression lasted for a long time instead of being a short-term response to the crisis.

In 2020, there were 56 arrests, despite the COVID-19 epidemic, which caused a lot of problems. This figure shows that law enforcement proceeded without interruption.

By 2025, at least 21 arrests had been documented at the time of data compilation. While the figure may not cover the full year, we say it points to the continuation of the same pattern, with no clear sign of a reversal.

This timeline does not claim to record every case. Rather, it provides an overview of a narrowing space for free expression and the increasing legal and personal consequences faced by those who speak out in Vietnamese society.

Has Việt Nam Met the EVFTA Compliance with Human Rights?

The pattern of arrests and convictions of dissident voices was already established by the time the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement entered into force in 2020, and it persisted in subsequent years.

Based on the data in this article, Việt Nam has not met the EVFTA’s human rights conditions in substance, and the post-EVFTA arrest record directly contradicts the agreement’s underlying assumptions.

The EVFTA was presented to the European Parliament and member states on the premise that trade integration would catalyze human rights progress – specifically through substantive legal reform, the strengthening of labor rights, and a marked reduction in political repression. The arrest data from 2015–2025 shows the opposite dynamic.

Most critically, the EVFTA entered into force in August 2020, yet The Vietnamese Magazine’s dataset shows:

- continued arrests of political prisoners after 2020,

- sustained use of the same vague criminal provisions (Articles 117, 331, 318),

- and ongoing long prison sentences imposed well into the EVFTA period.

The trade agreement failed to deter repression, representing a clear breakdown in policy conditionality. In policy terms, this was a failure of conditionality.

Supporters of the EVFTA might argue that Việt Nam was on a reform trajectory, citing labour law amendments and institutional dialogue. But the arrest data reveals a parallel—and dominant—trajectory: the criminal justice system continues to be used as a tool of political control.

We can take a look at the three points that are decisive.

First, the legal tools of repression remain unchanged. The most frequently charged articles, Article 117 (“anti-state propaganda”), Article 331 (“abusing democratic freedoms”), and Article 318 (“disturbing public order”), are precisely the provisions EU institutions and human-rights bodies have criticized for years.

Their dominance after 2020 demonstrates that Việt Nam did not narrow or restrain their use in response to EVFTA commitments. In fact, Việt Nam just sentenced Nguyễn Văn Đài and Lê Trung Khoa to 17 years under Article 117 on Dec. 31, 2025.

Secondly, repression in Việt Nam is not episodic; it is institutional. Arrests occur across multiple years, political cycles, and issue areas (journalism, religion, environmental advocacy, and labour organizing). This pattern refutes any argument that abuses are the result of “local excesses” or temporary security concerns.

Third and lastly, “Release” does not equal an improvement in rights. Even where prisoners are listed as released, many remain under probation, surveillance, or informal restrictions. This weakens claims that post-EVFTA outcomes represent normalization or liberalization.

The EVFTA’s human rights clause is legally anchored in the EU-Vietnam Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, which treats respect for human rights as an “essential element.” If that clause is taken seriously, then persistent political arrests should trigger consequences or, at a minimum, formal escalation.

Instead, the EU continued trade implementation largely uninterrupted; human rights dialogues continued without measurable benchmarks; and no enforcement mechanism was activated in response to arrests.

This sends a clear signal: human rights conditionality is politically subordinate to trade interests.

When the arrest data is treated as primary evidence rather than an inconvenient backdrop, the conclusion is unavoidable: Việt Nam has not fulfilled the EVFTA’s human rights conditions in any meaningful sense, and the EU has accepted this non-compliance.

The EVFTA did not halt repression, did not reduce abusive laws, and did not protect peaceful civic actors. Instead, it normalized a situation in which economic integration advanced while political imprisonment continued.

The question is no longer whether the EVFTA “encouraged reform,” but whether the EU knowingly traded away its leverage while repression remained predictable, documented, and measurable.

References:

- Database of persecuted activists in Vietnam. (n.d.). https://the88project.org/database/

- Thereporter. (2018, June 10). Vietnam, a step closer to democracy with the latest nationwide protests?. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2018/06/vietnam-a-step-closer-to-democracy-with-the-latest-nationwide-protests/

- Thereporter. (2018b, June 29). Black Sundays report: Vietnamese people’s response to police brutality during June 2018 protests. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2018/06/black-sundays-report-vietnamese-peoples-response-to-police-brutality-during-june-2018-protests/

- Vietnam free trade agreement. EU. (n.d.). https://trade.ec.europa.eu/access-to-markets/en/content/eu-vietnam-free-trade-agreement?utm_source=chatgpt.com