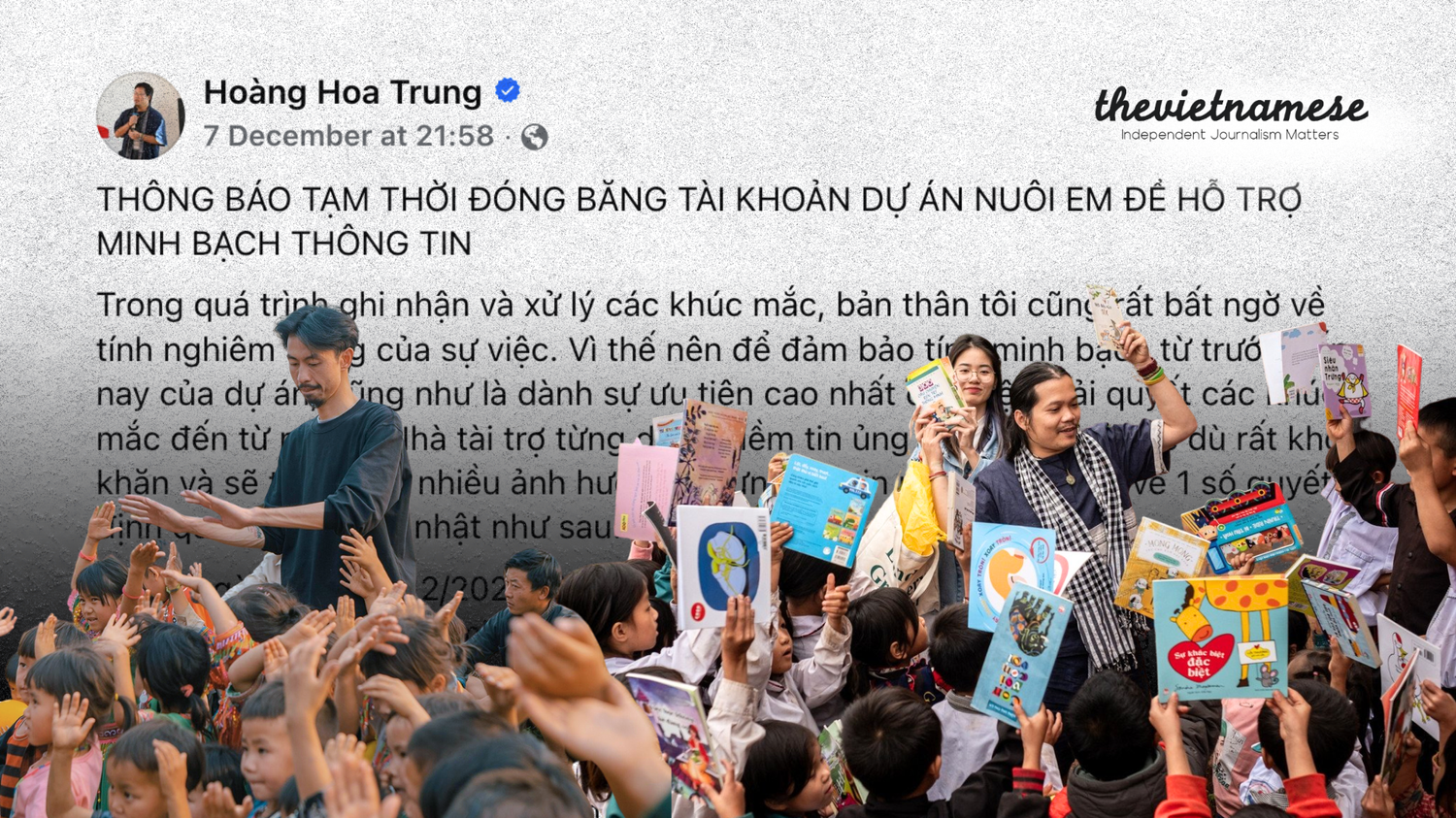

The “Nuôi Em” (Raise a Sibling) Project, one of the most prominent charitable initiatives in Việt Nam, is facing an unprecedented wave of criticism. [1] The controversy has spread so widely that the Criminal Investigation Department has instructed local police to urgently verify the project’s activities. [2]

This is not the first time Nuôi Em has sparked debate. When it gained widespread attention in 2023 following singer Đen Vâu’s music video “Nấu cơm cho em,” critics raised concerns about sustainability and the ethics of using children’s images to solicit donations.

However, the current backlash is different; it focuses directly on financial transparency. Many “sponsors” and donors have discovered that their personal “Nuôi Em ID codes” were duplicated, while others report being urged to donate for children who had already left the program.

Amid this organizational scandal, several respected development experts have called for Việt Nam to revisit the Law on Associations, a piece of legislation that has been shelved for nearly a decade. [3] While the law is often seen as a solution to such governance issues, the question remains: is this really the right time to reconsider it?

A Chapter from a Distant Past

The legal history of the Law on Associations in Việt Nam is defined by a document from 1957. Just one day after his 67th birthday, President Hồ Chí Minh promulgated Decree No. 101-SL/L.003 on the right to freedom of assembly. [4] Though only a page long, it established a strict “permission-based” framework.

Specifically, Article 3 of the decree states: “In order to ensure public order and security, public assemblies, except for meetings specified in Article 2, must be granted prior permission by local administrative authorities.” This provision became the foundation for Việt Nam’s long-standing “permission-based” approach to public gatherings.

Moreover, Article 9 included a rare provision: “All regulations contrary to this decree are hereby annulled.” In other words, the decree imposed a kind of legal “command” that no subsequent law could override.

Following the Đổi Mới reforms, discussions began in the early 1990s to replace Decree 101 and grant citizens greater freedoms. However, progress was slow. In 2003, the government issued Decree No. 88/2003/NĐ-CP, which, rather than replacing the 1957 decree, continued its restrictive spirit and cited it directly. [5]

The debate peaked between 2005 and 2006. In 2005, the government released its first official draft Law on Associations, which faced immediate backlash for preserving the old philosophy. In response, the Vietnam Union of Science and Technology Associations (VUSTA) took the unprecedented step of drafting its own alternative law in 2006. [6] VUSTA’s version proposed replacing the “permission” model with a “registration” mechanism to give civil groups more operational space. This period likely marked the height of public engagement on the issue, even without today’s digital tools.

The outcome, however, is well known. Despite the intense public discourse and a new draft introduced to the National Assembly in 2016, the legislation was ultimately withdrawn. [7] It has remained off the agenda ever since.

Pushback from Civil Society

Why was the Law on Associations never passed? According to a 2024 study by scholar Phuong Nguyen-Pochan, the answer lies not in a lack of political will, but in the specific dynamics of the 2016 legislative attempt. [8]

The primary reason for the law’s failure was strong resistance from development experts and domestic NGOs. These groups argued that the 2016 draft merely continued to impose heavy restrictions on freedom of association rather than reforming them. Notable intellectuals, including Atty. Trương Hồng Quang and Cao Vũ Minh (Secretary-General of the Legislative Studies Journal), alongside organizations like VUSTA, criticized the draft for relying on outdated regulatory approaches. They demanded a fundamental reconsideration of how “associations” were defined and questioned the legal status assigned to civil organizations.

Unlike in neighboring China, non-state actors in Việt Nam during this period held significant influence over policymaking. [9] The broad and heated public debate they generated likely forced the government to halt the legislative effort.

A House Divided

According to Phuong Nguyen-Pochan, the second reason for the shelving of the Law on Associations lies in the internal divisions of the Communist Party. While often viewed as a monolith, Việt Nam’s authoritarian system is prone to intense factional conflict—a reality that dictates the fate of legal reforms. [10]

Alexander Vuving, in a 2016 analysis, categorized these internal divisions into four competing currents: [11]

- Conservatives: Exemplified by the late General Secretary Nguyễn Phú Trọng, this bloc is anti-Western and focused primarily on defending the regime.

- Modernizers: This group advocates for reform, national development, and integration with the West.

- Moderates: This faction attempts to balance the preservation of the regime with the need for modernization.

- Rent-seekers: This group blends communist control with crony capitalism, prioritizing financial gain and maintaining authoritarian politics.

Nguyen-Pochan argues that the debates over the Law on Associations, particularly from 2005 to 2006, exposed deep rifts between the reformist and conservative camps.

By 2016, when the draft law was ready for debate, the political landscape had shifted again. This period coincided with the Communist Party’s 12th Congress, a pivotal event that, according to Vuving, signaled the weakening of rent-seeking groups and a resurgence of modernization-oriented forces. [12]

In this authoritarian-pluralist environment, the momentum of reformists likely played a key role. A draft law seen as restricting civic freedom may have been withdrawn simply to pacify public sentiment during a sensitive political transition.

Based on the current landscape, it is not the right time to revisit the Law on Associations. While a legal framework to protect civil organizations is undeniably important, the current political moment is uniquely hostile to such reforms.

The legislative environment in 2025 has been defined by speed and restriction. Acting under directive, the National Assembly has fast-tracked an extraordinary volume of bills, including constitutional amendments completed in just 43 days in June. [13] [14]

The pace has been so frantic that National Assembly Chairman Trần Thanh Mẫn famously remarked: “We’re not Sun Wukong—how can we pass laws the day after receiving them?” [15]

More concerning than the speed is the direction. Recent legislation consistently empowers the security apparatus at the expense of civil liberties and public freedoms. The revised Press Law now compels journalists to reveal sources to the Ministry of Public Security, [16] while the revised Cybersecurity Law mandates that companies identify and hand over user IP addresses. [17]

If a progressive Law on Associations could not survive the “blossoming” era of civil society, it has no chance in this climate. Pushing to replace the restrictive Decree 126/2024/NĐ-CP now would likely backfire, resulting in a law that is even more draconian than the decree it replaces. [18]

With the 15th Party Central Committee conference unscheduled and the 14th National Congress looming, Việt Nam is in a fragile political transition. The fate of the Law on Associations must remain on hold. For now, the wisest course for citizens is to stay alert and observe, preserving their energy for a moment when protecting their rights is actually possible.

Sa Huỳnh wrote this article in Vietnamese and published it in Luật Khoa Magazine on Dec. 18, 2025. Đàm Vĩnh Hằng translated it into English for The Vietnamese Magazine.

- Hoàng Nam. (2025, December 17). Bị nghi vấn về tài chính, dự án Nuôi Em đóng băng tài khoản để giải trình. Luật Khoa Tạp Chí. https://luatkhoa.com/2025/12/bi-nghi-van-ve-tai-chinh-du-an-nuoi-em-dong-bang-tai-khoan-de-giai-trinh/

- Trọng, D. (2025, December 15). Bộ Công an thông tin về việc xác minh dự án Nuôi Em. TUOI TRE ONLINE. https://tuoitre.vn/bo-cong-an-thong-tin-ve-viec-xac-minh-du-an-nuoi-em-2025121510322058.htm

- See:: https://www.facebook.com/son.pham.2012/posts/pfbid0VD6mSmkLdJDcMZitnqbCKKTF2Q73nwXKfDAvvaquJqWARQN83beFNUkVX4yDcVcbl

- Thuvienphapluat.Vn. (2025, January 10). Luật về quyền tự do hội họp 1957. THƯ VIỆN PHÁP LUẬT. https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Quyen-dan-su/Luat-quyen-tu-do-hoi-hop-1957-101-SL-L-003-36793.aspx

- Moha.Gov.Vn, & Vụ, B. N. (2009, November 4). Nghị định số 88/2003/NĐ-CP ngày 30/7/2003 của Chính phủ. moha.gov.vn. https://moha.gov.vn/to-chuc-phi-chinh-phu/huong-dan-xay-dung-dieu-le-va-quy-che-hoat-dong-cua-hoi-to-chuc-phi-chinh-phu/nghi-dinh-so-882003nd-cp-ngay-3072003-cua-chinh-ph-d748-t54928.html

- DỰ THẢO LUẬT VỀ HỘI – VIB Online. (n.d.). VIB Online. https://vibonline.com.vn/du_thao/du-thao-luat-ve-hoi

- Thuvienphapluat.Vn. (2025, January 10). Dự thảo Luật về hội do Quốc hội ban hành. THƯ VIỆN PHÁP LUẬT. https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bo-may-hanh-chinh/Luat-ve-hoi-280232.aspx

- Nguyen-Pochan, Thi Thanh. “The Draft Law on Association in Vietnam: Legal, Political, and Practical Norms under Debate.” The Palgrave Handbook of Political Norms in Southeast Asia, 2024, 81–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-9655-1_5.

- Nt, tr 87.

- Sa Huỳnh. (2025, August 12). Why constitutional review failed to take root in Việt Nam. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2025/08/why-constitutional-review-failed-to-take-root-in-viet-nam/

- Vuving, Alexander. “The 2016 Leadership Change in Vietnam and Its Long-Term Implications.” Southeast Asian Affairs SEAA17, no. 1 (2017): 426–27. https://doi.org/10.1355/aa17-1x.

- Nt, tr 432.

- Bảo Khánh. (2025, June 26). Hoàn tất sửa đổi Hiến pháp trong 43 ngày: Những điều bạn cần biết. Luật Khoa tạp chí. https://luatkhoa.com/2025/06/hoan-tat-sua-doi-hien-phap-trong-43-ngay-nhung-dieu-ban-can-biet/

- The Vietnamese Magazine. (2025, December 15). National Assembly pushes through record number of laws, expands police powers over the media. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2025/12/national-assembly-pushes-through-record-number-of-laws-expands-police-powers-over-the-media/

- Bối Thủy. (2025, October 17). Lawmaking at lightning speed: Việt Nam’s citizens pay the price. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2025/10/lawmaking-at-lightning-speed-viet-nams-citizens-pay-the-price/

- The Vietnamese Magazine. (2025, December 15). National Assembly pushes through record number of laws, expands police powers over the media. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2025/12/national-assembly-pushes-through-record-number-of-laws-expands-police-powers-over-the-media/

- Trường An. (2025, December 12). The quiet passing of Việt Nam’s 2025 cybersecurity law. The Vietnamese Magazine. https://www.thevietnamese.org/2025/12/the-quiet-passing-of-viet-nams-2025-cybersecurity-law/

- Moha.Gov.Vn, & Vụ, B. N. (2024, October 11). Chính phủ ban hành Nghị định quy định về tổ chức, hoạt động và quản lý hội. moha.gov.vn. https://moha.gov.vn/tintuc/Pages/listbnv.aspx?Cat=610&ItemID=56433