When Nobel laureate James Watson died at 97 in November, obituaries around the world painted a divided portrait: a scientific visionary who co-discovered the double helix of DNA – and a controversial figure long condemned for making racially charged statements about intelligence and genetics.

Advertisement

In the West, the American molecular biologist’s legacy was increasingly overshadowed by the fallout from those remarks, culminating in New York’s Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (CSHL) severing ties with him in 2019.

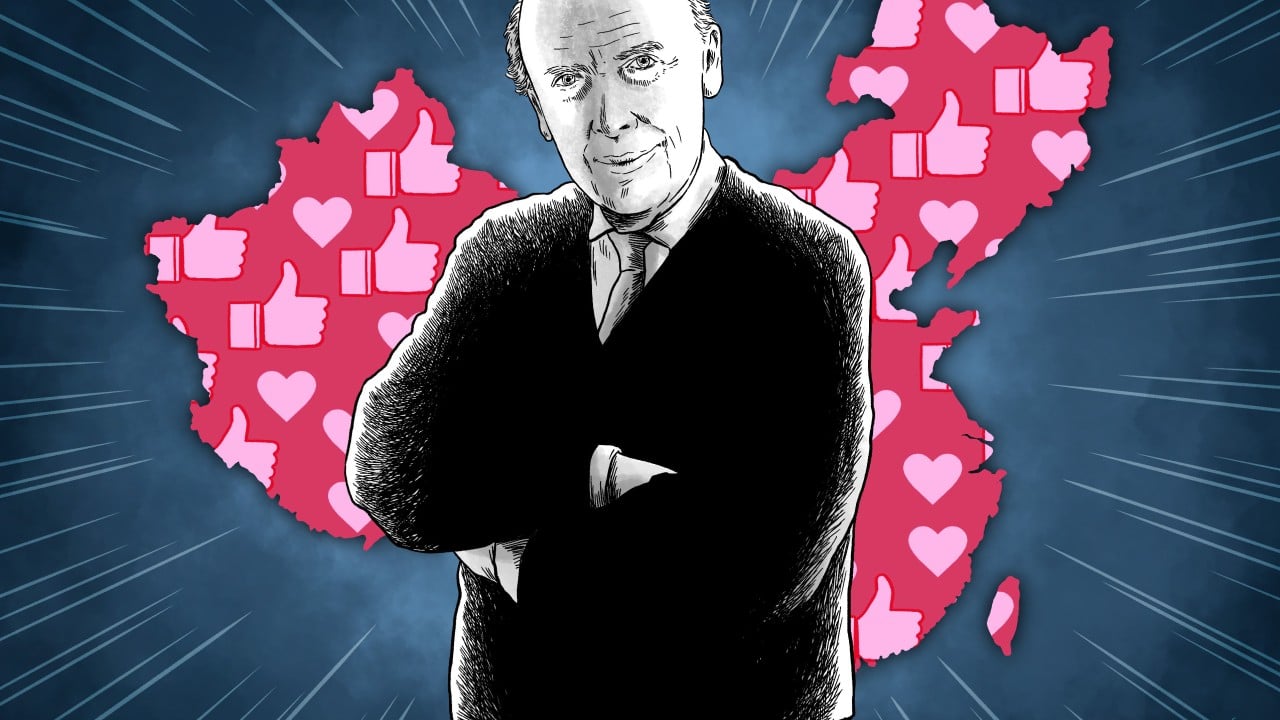

Yet thousands of kilometres away, in laboratories and academic communities across China, a different profile emerged – one less focused on scandal than on sacrifice, mentorship and scientific solidarity.

In China, Watson is not mainly remembered as a provocateur, but as a pioneer who saw potential in a nation still rebuilding its scientific foundations – and chose to invest in it when few others did.

From the 1980s onwards, long before China became a global powerhouse in genomics and biotechnology, Watson was quietly laying the intellectual and institutional groundwork for its rise.

Advertisement

He sent books, journals and bacterial strains to Chinese researchers cut off from Western science. He opened the doors of Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory (CSHL) to dozens of Chinese scholars at a time when such opportunities were rare.